Page 54 - Hamlet: The Cambridge Dover Wilson Shakespeare

P. 54

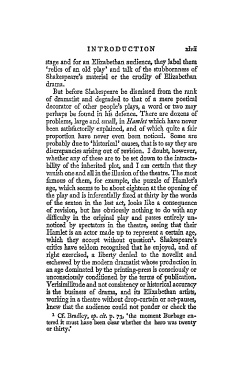

I N T R O D U C T I O N xlvii

stage and for an Elizabethan audience, they label them

•relics of an old play' and talk of the stubbornness of

Shakespeare's material or the crudity of Elizabethan

drama.

But before Shakespeare be dismissed from the rank

of dramatist and degraded to that of a mere poetical

decorator of other people's plays, a word or two may

perhaps be found in his defence. There are dozens of

problems, large and small, in Hamlet which have never

been satisfactorily explained, and of which quite a fair

proportion have never even been noticed. Some are

probably due to 'historical' causes, that is to say they are

discrepancies arising out of revision. I doubt, however,

whether any of these are to be set down to the intracta-

bility of the inherited plot, and I am certain that they

vanish one and all in the illusion of the theatre. The most

famous of them, for example, the puzzle of Hamlet's

age, which seems to be about eighteen at the opening of

the play and is inferentially fixed at thirty by the words

of the sexton in the last act, looks like a consequence

of revision, but has obviously nothing to do with any

difficulty in the original play and passes entirely un-

noticed by spectators in the theatre, seeing that their

Hamlet is an actor made up to represent a certain age,

1

which they accept without question . Shakespeare's

critics have seldom recognised that he enjoyed, and of

right exercised, a liberty denied to the novelist and

eschewed by the modern dramatist whose production in

an age dominated by the printing-press is consciously or

unconsciously conditioned by the terms of publication.

Verisimilitude and not consistency or historical accuracy

is the business of drama, and its Elizabethan artists,

working in a theatre without drop-curtain or act-pauses,

knew that the audience could not ponder or check the

1

Cf. Bradley, op. cit. p. 73, 'the moment Burbage en-

tered it must have been dear whether the hero was twenty

or thirty,'