Page 232 - Cardiac Nursing

P. 232

1

1:1

1:1

/09

/09

1

M

Pa

Pa

7 P

7 P

M

q

q

xd

10.

10.

q

6

/29

/29

xd

6

6

g

ara

a

a

t

ara

ara

In

c.

c.

a

a

In

e 2

08

08

g

g

e 2

p

p

t

A

A

p

4-2

K34

LWBK340-c09_

09_

0-c

20

LWB K34 0-c 09_ p p pp204-210.qxd 6/29/09 11:17 PM Page 208 Aptara Inc.

4-2

20

LWB

208 PA R T I I / Physiologic and Pathologic Responses

increasing heart rate and contractility. At rest the parasympathetic show more neutrophils and fewer macrophages in fluid from older

nervous system prevails, slowing down the heart rate. The extent (70 to 80 years) than from younger subjects (19 to 34 years). 20,21

of parasympathetic tone is small in older people. Heart rate vari- The activity of the cilia is decreased, producing less ciliary clear-

ability, a reflection of balance between the sympathetic and ance. Decreased cough reflex related to decreased cilia activity to-

parasympathetic nervous systems, declines steadily with aging. 5 gether with decreased immune system function increase suscepti-

The decline in heart rate variability is related to decreased bility to lower respiratory infection, mechanical irritation, and,

parasympathetic activity, because it is the low-frequency compo- possibly, tumor formation.

7

nent of the variability that is decreased. Decreased heart rate vari- There is an age-related increase in the ratio of elastin-to-collagen

ability has been associated with poor outcomes in people with car- in the lung parenchyma that may contribute to increased lung

diovascular disease. compliance, reduced expiratory airway diameter, or airflow limi-

The aging cardiovascular system demonstrates decreased re- tation. 22,23 Increased calcification of the thoracic joints (spine,

sponse to -adrenoreceptor stimulation. 15 Decreased responsive- ribs, and sternum) and reduced intercostal muscle strength pro-

ness is not caused by a decreased number of -receptors, but to a duce a decrease in chest wall compliance with aging and an in-

decrease in affinity of -agonists for the receptors and decreased creased anteroposterior diameter of the chest. The resulting re-

efficacy of postreceptor intercellular coupling responsible for mus- duced mobility of the thorax leads to increased residual air volume

cle contraction. 8,9 Stimulation of 1 -receptors in the ventricles in- and to a breathing pattern that is augmented by the increased use

creases heart rate and contractility. Increased end-diastolic volume of diaphragmatic and abdominal muscles in breathing.

also increases cardiac contractility (Frank–Starling mechanism). If

the ventricular response to 1 -receptor stimulation is reduced in Functional Changes

the aging heart, the ventricles are more dependent on adequate

filling. Consequently, the aging heart is less tolerant of hypo- The typical changes in lung function with age include decreased

ventilation. Decreased -receptor responsiveness in the vascula- lung recoil, increased closing volume, altered lung volumes, and

ture produces less vasodilation and higher resting blood pressure. decreased maximum expiratory flow volume. 22 Nonemphysema-

The combined effect of changes in autonomic function is de- tous enlargement of the alveoli is accepted as a normal change of

creased baroreflex function and response to physiologic stressors. 8 aging. The effect of this change is decreased efficiency of gas-

diffusing capacity and increased residual volume.

During expiration, airways in the dependent lung regions close

RESPIRATORY CHANGES and no longer participate in respiration. With aging, the lung vol-

ume at which these airways close (closing volume) may exceed the

In the absence of disease, the changes that occur in the lungs from functional residual capacity, leading to closure of distal airways be-

maturity through the aging process are so gradual that the lungs fore the end of a normal breath. 22 Loss of lung recoil and the ef-

are capable of providing normal gas exchange throughout life. fects of gravity on the dependent areas of the lungs allow the air-

However, the lungs are continuously exposed to the external envi- ways to close at a higher lung volume and lead to nonuniformity

ronment and to various internal assaults; hence, it is difficult to of ventilation (Fig. 9-4).

separate changes caused solely by aging from those related to in- After adjustment for height, total lung capacity does not

jury or disease processes. change with age. 22,23 There is an increase, however, in residual

volume for reasons previously discussed and in the ratio of resid-

Structural Changes ual volume-to-total lung capacity. When increased closing capac-

ity closes terminal airways, these airways no longer actively par-

The aging lung undergoes gradual, subtle changes. Host defense ticipate in ventilation, resulting in reduced maximal expiratory

V V

mechanisms of airway clearance and immune system function re- flow (V max ) and in decreased expiratory volume measured in the

spond less vigorously with age. Studies of bronchoalveolar lavage first second of forced expiration (FEV 1 ).

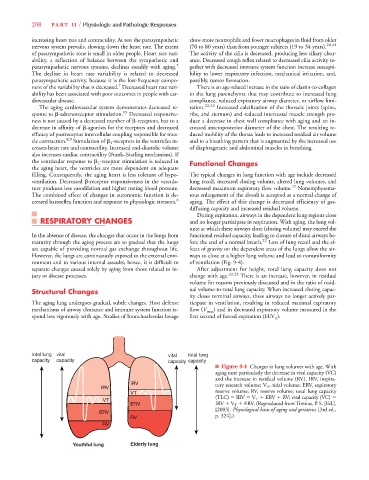

total lung vital vital total lung

capacity capacity capacity capacity

■ Figure 9-4 Changes in lung volumes with age. With

aging note particularly the decrease in vital capacity (VC)

and the increase in residual volume (RV). IRV, inspira-

IRV tory research volume; V T , tidal volume; ERV, expiratory

V V

IRV

VT reserve volume; RV, reserve volume; total lung capacity

(TLC) IRV V T

ERV

RV; vital capacity (VC)

V V

VT

V V

ERV IRV

V T

ERV. (Reproduced from Timiras, P. S. [Ed.].

[2003]. Physiological basis of aging and geriatrics [3rd ed.,

ERV

RV p. 324].)

RV

Youthful lung Elderly lung