Page 596 - Elementary_Linear_Algebra_with_Applications_Anton__9_edition

P. 596

Let be the vector space of functions with continuous first derivatives on , let

be the vector space of all real-valued functions defined on , and let be the

differentiation transformation . The kernel of D is the set of functions in V with derivative zero. From calculus,

this is the set of constant functions on .

Properties of Kernel and Range

In all of the preceding examples, and turned out to be subspaces. In Examples Example 2, Example 3, and

Example 5 they were either the zero subspace or the entire vector space. In Example 4 the kernel was a line through the origin,

and the range was a plane through the origin, both of which are subspaces of . All of this is not accidental; it is a consequence

of the following general result.

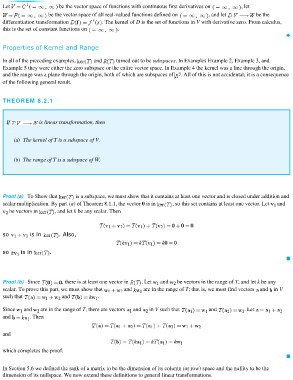

THEOREM 8.2.1

If is linear transformation, then

(a) The kernel of T is a subspace of V.

(b) The range of T is a subspace of W.

Proof (a) To Show that is a subspace, we must show that it contains at least one vector and is closed under addition and

scalar multiplication. By part (a) of Theorem 8.1.1, the vector 0 is in , so this set contains at least one vector. Let and

be vectors in , and let k be any scalar. Then

so is in . Also,

so is in .

Proof (b) Since , there is at least one vector in . Let and be vectors in the range of T, and let k be any

are in the range of T; that is, we must find vectors and in V

scalar. To prove this part, we must show that and

such that and .

Since and are in the range of T, there are vectors and in V such that and . Let

and . Then

and

which completes the proof.

In Section 5.6 we defined the rank of a matrix to be the dimension of its column (or row) space and the nullity to be the

dimension of its nullspace. We now extend these definitions to general linear transformations.