Page 1128 - Williams Hematology ( PDFDrive )

P. 1128

1102 Part VIII: Monocytes and Macrophages Chapter 71: Inflammatory and Malignant Histiocytosis 1103

The relatively high rate of high-risk multisystem LCH in identical twins and cytokine and chemokine receptors have been hypothesized to

compared to presumed fraternal twins may be explained by shared pre- play roles in LCH pathogenesis, creating a local “cytokine storm” as

cursor cells as well as the possibility of shared genes. An increased fre- well as increased circulating proinflammatory cytokines, including

13

quency of family members with thyroid disease, family members with tumor necrosis factor α, soluble interleukin (IL)-2 receptor α, RANKL

14

16

15

other cancers, in vitro fertilization, and parental exposure to metal (receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand), osteoprotegerin, and

have also been reported as potential associations. Although inheritance osteopontin. 4,30,31 Although MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)

of penetrant mendelian “LCH genes” in the majority of cases seems pathway activation in maturing DCs may drive differentiation of LCH

unlikely, it remains possible that there are inherited genes associated DCs, inflammation likely plays a role in the clinical manifestations and

with increased risk of developing LCH. possibly also in tumor maintenance: A unique phenomenon in LCH

is that disruption of solitary LCH lesions often results in spontaneous

Molecular Pathology resolution, even without clean margins.

The focus of studies and reviews on LCH over the past decades has been

on either an immune or a neoplastic disorder. The competing mod- CLINICAL FEATURES

els have been (1) an inappropriate activation of an otherwise normal

epidermal LC or (2) a neoplastic transformation of the epidermal LC. LCH usually presents with a skin rash or painful bone lesion. Systemic

Twenty years ago, CD1a+ cells from LCH lesions were described as symptoms of fever, weight loss, diarrhea, edema, dyspnea, polydipsia,

clonal, based on non–random X inactivation. 17,18 Subsequently, somatic and polyuria may also occur.

activating mutations in the BRAF oncogene were reported in 57 percent In LCH, involvement of specific organs at the time of diagnosis

19

of LCH histopathologic specimens, with subsequent studies validating determines the designation “high-risk” or “low-risk.” Organs that indi-

the recurrent BRAF V600E mutation at high frequency. 5,20–22 BRAF is the cate high-risk of progression include liver, spleen, and marrow. Organs

central kinase of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, which is essential that indicate low-risk of progression include skin, bone, lung, lymph

to numerous cell functions and is frequently mutated in cancer cells. nodes, and pituitary gland. Patients may present with disease in one site

23

Significance of BRAF V600E as a driver mutation in LCH is supported by or organ (single site or single system) or in multiple sites or organs (mul-

early reports of clinical responses to BRAF inhibition in adults with tisystem). Treatment decisions for patients are based on whether or not

combined LCH and ECD. Other recurrent somatic mutations in LCH organs that indicate high-risk or low-risk of progression are involved,

24

may be uncovered. and if LCH presents as a single site or as a multisystem disease. Patients

can have LCH of the skin, bone, lymph nodes, and pituitary in any com-

Cell of Origin bination and still be considered to have a low-risk of progression.

The cell of origin of LCH has been assumed to be the epidermal LC

based on phenotypic similarities discussed above. However, the tran- Single-Site Disease Presentation

scriptome of CD207+ cells from LCH lesions is more consistent with In this situation the disease presents with involvement of one site, which

an immature myeloid DC phenotype than with the transcriptome of can be skin, oral mucosa, bone, lymph nodes, pituitary, or thymus.

epidermal LCs. Furthermore, DC maturation may be heterogeneous Skin Lesions simulating seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp may

4

within lesions, with variable CD1a+/CD207− populations. 25,26 Immuno- be mistaken for prolonged “cradle cap” in infants. The lesions may be

histochemical staining antibodies specific for BRAF V600E revealed that localized to intertriginous areas or may be diffuse (Fig. 71–1). The most

the mutations are not limited to CD207+ cells within LCH lesions, common skin flexures affected are the groin, the perianal area, back of

but also are found in CD207-negative subpopulations. Using the the ears, the neck, the armpits, and, in women, the crease below the

21

BRAF V600E mutation as a “bar code,” cells that carry the mutation were breasts. Infants may also present with brown to purplish papules over

identified in circulating myelomonocytic precursors in blood and in any part of their body. This latter manifestation may be self-limited as

hematopoietic stem cells in marrow aspirates of patients with clinical

high-risk LCH, but not in patients with single-lesion low-risk LCH.

The functional significance of this observation was supported by the

ability of forced expression of BRAF V600E in myelomonocytic precursors

5

(CD11c+ cells) to induce a disseminated LCH-like phenotype in mice.

We therefore hypothesize that the state of differentiation of the cell in

which LCH arises determines the clinical manifestations of the disease;

pathologic ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) activation in

stem cell or early myelomonocytic precursor resulted in disseminated

high-risk disease whereas ERK activation in tissue-restricted precursor

resulted in localized disease. These observations define LCH as a mye-

loid neoplasm.

Inflammation and Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Although ERK hyperactivation may drive differentiation and prolifera-

tion of myelomonocytic precursors in LCH, the mechanisms that drive

inflammation in the LCH lesions are not currently understood. The

LCH DCs make up a median of 8 percent of the cells within lesions.

5

Like physiologically activated DCs, they express high levels of T-cell

costimulatory molecules and proinflammatory cytokines. 4,27,28 The LCH

lesion’s inflammatory infiltrate includes lymphocytes, macrophages,

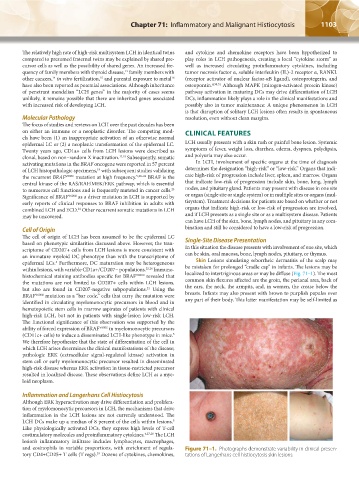

and eosinophils in variable proportions, with enrichment of regula- Figure 71–1. Photographs demonstrate variability in clinical presen-

tory CD4+CD25+ T cells (T regs). Dozens of cytokines, chemokines, tations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis skin lesions.

29

Kaushansky_chapter 71_p1101-1120.indd 1103 9/17/15 3:49 PM