Page 850 - Williams Hematology ( PDFDrive )

P. 850

824 Part VI: The Erythrocyte Chapter 54: Hemolytic Anemia Resulting from Immune Injury 825

pathogenic significance of these associations is poorly understood, but secondary (1) when AHA and the underlying disease occur together

most of the associated diseases involve components of the immune sys- with greater frequency than can be accounted for by chance alone; (2)

tem, either by neoplasia or by aberrant immunopathologic responses. when the AHA reverses simultaneously with correction of the associ-

ated disease; or (3) when AHA and the associated disease are related

Drug-Mediated Cases by evidence of immunologic aberration. Using these criteria, the fre-

11

Certain drugs also mediate immune injury to RBCs, and three general quency of primary warm-antibody AHA probably is closer to 50 percent

mechanisms are recognized (see Table 54–1 and Fig. 54–1). This classi- of all cases. Careful followup of patients with primary AHA is essential,

fication is based on the effector mechanism of RBC injury, because the because hemolytic anemia may be the presenting finding in a patient

induction mechanism for formation of drug-related RBC antibodies is who subsequently develops overt evidence of an underlying disorder.

unknown. Two of the mechanisms, hapten-drug adsorption and ternary For example, in one series, 18 of 107 patients with AHA developed a

complex formation, involve drug-dependent antibodies. In the third malignant lymphoproliferative disorder at a median of 26.5 months

mechanism, the drugs in question appear to induce formation of true after diagnosis of the AHA. 119

autoantibodies capable of reacting with human RBCs in the absence Warm-antibody AHA has been diagnosed in people of all ages,

of the inciting drug. These types of drug-mediated immune injury to from infants to the elderly. The majority of patients are older than 40

RBCs often are referred to collectively as drug-immune hemolytic ane- years of age, with peak incidence around the seventh decade. This age

mia to distinguish them from de novo AHA. Distinguishing among the distribution probably reflects, in part, the increased frequency of lym-

mechanisms is not always possible, and some cases involve a combina- phoproliferative malignancies in the elderly, resulting in an age-related

tion of mechanisms. In addition, drug-related non-immunologic pro- increase in the frequency of secondary AHA. Although multiple cases

tein adsorption by RBCs may result in a positive DAT without actual are occasionally observed in families, 120–122 most cases of primary AHA

RBC injury. This phenomenon should be distinguished from the three arise sporadically. Development of AHA does not have an apparent

forms of drug-immune RBC injury. Table 54–2 lists drugs documented association with any particular human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplo-

to cause either immune injury or a positive DAT. type or other genetic factor.

Cold agglutinin disease is less common than warm-antibody

24

EPIDEMIOLOGY AHA, with a prevalence of approximately 14 per 1 million population,

Women

10,11,123

accounting for only 10 to 20 percent of all cases of AHA.

The annual incidence of warm-antibody AHA is 1 per 75,000 to 80,000 are affected more commonly than men. 10,11 No genetic or racial factors

population. Estimates of the frequency of primary (idiopathic) AHA are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of this disease.

11

vary from 20 to 80 percent of all types of AHA, depending on the refer- Secondary cold agglutinin disease is seen most commonly in

ral patterns of the reporting center. 11,20,118 In general, AHA is considered adolescents or young adults as a self-limited process associated with

Fab Fab

Fab

Membrane

protein

TF Alb IgG Fibr.

A B C D

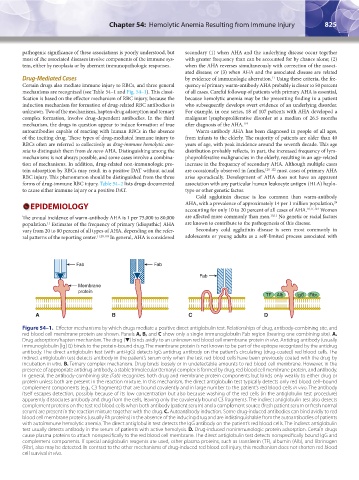

Figure 54–1. Effector mechanisms by which drugs mediate a positive direct antiglobulin test. Relationships of drug, antibody-combining site, and

red blood cell membrane protein are shown. Panels A, B, and C show only a single immunoglobulin Fab region (bearing one combining site). A.

Drug adsorption/hapten mechanism. The drug (▼) binds avidly to an unknown red blood cell membrane protein in vivo. Antidrug antibody (usually

immunoglobulin [Ig] G) binds to the protein-bound drug. The membrane protein is not known to be part of the epitope recognized by the antidrug

antibody. The direct antiglobulin test (with anti-IgG) detects IgG antidrug antibody on the patient’s circulating (drug-coated) red blood cells. The

indirect antiglobulin test detects antibody in the patient’s serum only when the test red blood cells have been previously coated with the drug by

incubation in vitro. B. Ternary complex mechanism. Drug binds loosely or in undetectable amounts to red blood cell membrane. However, in the

presence of appropriate antidrug antibody, a stable trimolecular (ternary) complex is formed by drug, red blood cell membrane protein, and antibody.

In general, the antibody-combining site (Fab) recognizes both drug and membrane protein components but binds only weakly to either drug or

protein unless both are present in the reaction mixture. In this mechanism, the direct antiglobulin test typically detects only red blood cell–bound

complement components (e.g., C3 fragments) that are bound covalently and in large number to the patient’s red blood cells in vivo. The antibody

itself escapes detection, possibly because of its low concentration but also because washing of the red cells (in the antiglobulin test procedure)

apparently dissociates antibody and drug from the cells, leaving only the covalently bound C3 fragments. The indirect antiglobulin test also detects

complement proteins on the test red blood cells when both antibody (patient serum) and a complement source (fresh patient serum or fresh normal

serum) are present in the reaction mixture together with the drug. C. Autoantibody induction. Some drug-induced antibodies can bind avidly to red

blood cell membrane proteins (usually Rh proteins) in the absence of the inducing drug and are indistinguishable from the autoantibodies of patients

with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. The direct antiglobulin test detects the IgG antibody on the patient’s red blood cells. The indirect antiglobulin

test usually detects antibody in the serum of patients with active hemolysis. D. Drug-induced nonimmunologic protein adsorption. Certain drugs

cause plasma proteins to attach nonspecifically to the red blood cell membrane. The direct antiglobulin test detects nonspecifically bound IgG and

complement components. If special antiglobulin reagents are used, other plasma proteins, such as transferrin (TF), albumin (Alb), and fibrinogen

(Fibr), also may be detected. In contrast to the other mechanisms of drug-induced red blood cell injury, this mechanism does not shorten red blood

cell survival in vivo.

Kaushansky_chapter 54_p0823-0846.indd 825 9/19/15 12:27 AM