Page 890 - Williams Hematology ( PDFDrive )

P. 890

864 Part VI: The Erythrocyte Chapter 56: Hypersplenism and Hyposplenism 865

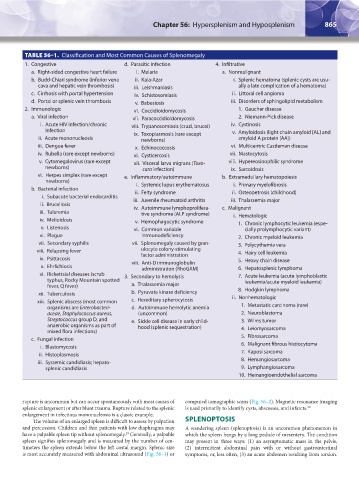

TABLE 56–1. Classification and Most Common Causes of Splenomegaly

1. Congestive d. Parasitic infection 4. Infiltrative

a. Right-sided congestive heart failure i. Malaria a. Nonmalignant

b. Budd-Chiari syndrome (inferior vena ii. Kala-Azar i. Splenic hematoma (splenic cysts are usu-

cava and hepatic vein thrombosis) iii. Leishmaniasis ally a late complication of a hematoma)

c. Cirrhosis with portal hypertension iv. Schistosomiasis ii. Littoral cell angioma

d. Portal or splenic vein thrombosis v. Babesiosis iii. Disorders of sphingolipid metabolism

2. Immunologic vi. Coccidioidomycosis 1. Gaucher disease

a. Viral infection vii. Paracoccidioidomycosis 2. Niemann-Pick disease

i. Acute HIV infection/chronic viii. Trypanosomiasis (cruzi, brucei) iv. Cystinosis

Infection ix. Toxoplasmosis (rare except v. Amyloidosis (light chain amyloid [AL] and

ii. Acute mononucleosis newborns) amyloid A protein [AA])

iii. Dengue fever x. Echinococcosis vi. Multicentric Castleman disease

iv. Rubella (rare except newborns) xi. Cysticercosis vii. Mastocytosis

v. Cytomegalovirus (rare except xii. Visceral larva migrans (Toxo- viii. Hypereosinophilic syndrome

newborns) cara infection) ix. Sarcoidosis

vi. Herpes simplex (rare except e. Inflammatory/autoimmune b. Extramedullary hematopoiesis

newborns) i. Systemic lupus erythematosus i. Primary myelofibrosis

b. Bacterial infection ii. Felty syndrome ii. Osteopetrosis (childhood)

i. Subacute bacterial endocarditis iii. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis iii. Thalassemia major

ii. Brucellosis iv. Autoimmune lymphoprolifera- c. Malignant

iii. Tularemia tive syndrome (ALP syndrome) i. Hematologic

iv. Melioidosis v. Hemophagocytic syndrome 1. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (espe-

v. Listeriosis vi. Common variable cially prolymphocytic variant)

vi. Plague immunodeficiency 2. Chronic myeloid leukemia

vii. Secondary syphilis vii. Splenomegaly caused by gran- 3. Polycythemia vera

viii. Relapsing fever ulocyte colony-stimulating 4. Hairy cell leukemia

ix. Psittacosis factor administration 5. Heavy chain disease

x. Ehrlichiosis viii. Anti-D immunoglobulin 6. Hepatosplenic lymphoma

administration (RhoGAM)

xi. Rickettsial diseases (scrub 3. Secondary to hemolysis 7. Acute leukemia (acute lymphoblastic

typhus, Rocky Mountain spotted leukemia/acute myeloid leukemia)

fever, Q fever) a. Thalassemia major 8. Hodgkin lymphoma

xii. Tuberculosis b. Pyruvate kinase deficiency ii. Nonhematologic

xiii. Splenic abscess (most common c. Hereditary spherocytosis

organisms are Enterobacteri- d. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia 1. Metastatic carcinoma (rare)

aceae, Staphylococcus aureus, (uncommon) 2. Neuroblastoma

Streptococcus group D, and e. Sickle cell disease in early child- 3. Wilms tumor

anaerobic organisms as part of hood (splenic sequestration) 4. Leiomyosarcoma

mixed flora infections)

c. Fungal infection 5. Fibrosarcoma

i. Blastomycosis 6. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

ii. Histoplasmosis 7. Kaposi sarcoma

iii. Systemic candidiasis; hepato- 8. Hemangiosarcoma

splenic candidiasis 9. Lymphangiosarcoma

10. Hemangioendothelial sarcoma

rupture is uncommon but can occur spontaneously with most causes of computed tomographic scans (Fig. 56–2). Magnetic resonance imaging

splenic enlargement or after blunt trauma. Rupture related to the splenic is used primarily to identify cysts, abscesses, and infarcts. 30

enlargement in infectious mononucleosis is a classic example.

The volume of an enlarged spleen is difficult to assess by palpation SPLENOPTOSIS

and percussion. Children and thin patients with low diaphragms may A wandering spleen (splenoptosis) is an uncommon phenomenon in

have a palpable spleen tip without splenomegaly. Generally, a palpable which the spleen hangs by a long pedicle of mesentery. The condition

29

spleen signifies splenomegaly and is measured by the number of cen- may present in three ways: (1) an asymptomatic mass in the pelvis,

timeters the spleen extends below the left costal margin. Splenic size (2) intermittent abdominal pain with or without gastrointestinal

is most accurately measured with abdominal ultrasound (Fig. 56–1) or symptoms, or, less often, (3) an acute abdomen resulting from torsion.

Kaushansky_chapter 56_p0863-0870.indd 865 9/17/15 3:05 PM