Page 73 - T-I JOURNAL19 4

P. 73

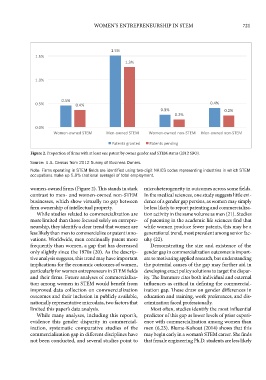

Figure 2. Proportion of firms with at least one patent by owner gender and STEM status (2012

SBO). WOMEN’S ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN STEM 721

1.5%

1.5%

1.3%

1.0%

0.5%

0.5% 0.4% 0.4%

0.3% 0.2%

0.2%

0.0%

Women-owned STEM Men-owned STEM Women-owned non-STEM Men-owned non-STEM

Patents granted Patents pending

Figure 2. Proportion of firms with at least one patent by owner gender and STEM status (2012 SBO).

Source: U.S. Census estimates from 2012 Survey of Business Owners.

Source: U.S. Census from 2012 Survey of Business Owners.

Note: Firms operating in STEM fields are identified using two-digit NAICS codes representing industries in which STEM

Note: Firms operating in STEM fields are identified using two-digit NAICS codes representing industries in

occupations make up 5.8% (national average) of total employment.

which STEM occupations make up 5.8% (national average) of total employment.

women-owned firms (Figure 2). This stands in stark microheterogeneity in outcomes across some fields.

contrast to men- and women-owned non-STEM In the medical sciences, one study suggests little evi-

businesses, which show virtually no gap between dence of a gender gap persists, as women may simply

firm ownership of intellectual property. be less likely to report patenting and commercializa-

While studies related to commercialization are tion activity in the same volume as men (21). Studies

more limited than those focused solely on entrepre- of patenting in the academic life sciences find that

neurship, they identify a clear trend that women are while women produce fewer patents, this may be a

less likely than men to commercialize or patent inno- generational trend, most prevalent among senior fac-

vations. Worldwide, men continually patent more ulty (22).

frequently than women, a gap that has decreased Demonstrating the size and existence of the

only slightly since the 1970s (20). As the descrip- gender gap in commercialization outcomes is import-

tive analysis suggests, this trend may have important ant to motivating applied research, but understanding

implications for the economic outcomes of women, the potential causes of the gap may further aid in

particularly for women entrepreneurs in STEM fields developing exact policy solutions to target the dispar-

and their firms. Future analyses of commercializa- ity. The literature cites both individual and external

tion among women in STEM would benefit from influences as critical in defining the commercial-

improved data collection on commercialization ization gap. These draw on gender differences in

outcomes and their inclusion in publicly available, education and training, work preferences, and dis-

nationally representative microdata, two factors that crimination faced professionally.

limited this paper’s data analysis. Most often, studies identify the most influential

While many analyses, including this report’s, predictor of this gap as lower levels of prior experi-

evidence this gender disparity in commercial- ence with commercialization among women than

ization, systematic comparative studies of the men (6,23). Blume-Kohout (2014) shows that this

commercialization gap in different disciplines have may begin early in a woman’s STEM career. She finds 11

not been conducted, and several studies point to that female engineering Ph.D. students are less likely