Page 7 - GeoPRISMS_Newsletter_Spring2019_42_Neat

P. 7

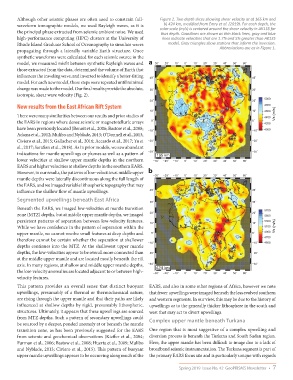

Although other seismic phases are often used to constrain full- Figure 2. Two depth slices showing shear velocity at a) 165 km and

b) 424 km, modified from Emry et al. (2019). For each depth, the

waveform tomographic models, we used Rayleigh waves, as it is color scale (m/s) is centered around the shear velocity in AK135 for

the principal phase extracted from seismic ambient noise. We used that depth. Coastlines are shown as thin black lines, gray and blue

high-performance computing (HPC) clusters at the University of lines indicate velocities that are 1.7% and 5% greater than AK135

Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography to simulate waves model. Gray triangles show stations that inform the inversion.

propagating through a laterally variable Earth structure. Once Abbreviations are as in Figure 1.

synthetic waveforms were calculated for each seismic source in the

model, we measured misfit between synthetic Rayleigh waves and a −30˚ −20˚ −10˚ 0˚ 10˚ 20˚ 30˚ 40˚ 50˚ 60˚

those extracted from the data, determined the volume of Earth that

influences the traveling wave, and inverted to identify a better-fitting 40˚ 40˚

model. For each new model, these steps were repeated until minimal

change was made to the model. Our final results provide the absolute, 30˚ 30˚

isotropic, shear wave velocity (Fig. 2). AP

5000

20˚ 20˚

New results from the East African Rift System AF 4800

10˚ MER 10˚ 4600

There were many similarities between our results and prior studies of SS TD 4400 Vs (m/s)

the EARS in regions where dense seismic or magnetotelluric arrays 0˚ VVP TC 0˚ 4200

have been previously located (Benoit et al., 2006; Bastow et al., 2008; −10˚ RVP −10˚ 4000

Adams et al., 2012; Mulibo and Nyblade, 2013; O’Donnell et al., 2013; DB LR MR

Civiero et al., 2015; Gallacher et al., 2016; Accardo et al., 2017; Yu et −20˚ OR ZC −20˚

al., 2017; Sarafian et al., 2018). As in prior models, we saw abundant KpC

indications for mantle upwellings or plumes as well as a pattern of −30˚ 165 km −30˚

lower velocities at shallow upper mantle depths in the northern −30˚ −20˚ −10˚ 0˚ 10˚ 20˚ 30˚ 40˚ 50˚ 60˚

EARS and higher velocities at shallow depths in the southern EARS.

However, in our results, the patterns of low-velocities at middle upper b

mantle depths were laterally discontinuous along the full length of −30˚ −20˚ −10˚ 0˚ 10˚ 20˚ 30˚ 40˚ 50˚ 60˚

the EARS, and we imaged variable lithospheric topography that may

influence the shallow flow of mantle upwellings. 40˚ 40˚

Segmented upwellings beneath East Africa 30˚ 30˚

Beneath the EARS, we imaged low-velocities at mantle transition 5700

zone (MTZ) depths, but at middle upper mantle depths, we imaged 20˚ 20˚ 5500

persistent patterns of separation between low-velocity features. 10˚ 10˚ 5300

While we have confidence in the pattern of separation within the 5100 Vs (m/s)

upper mantle, we cannot resolve small features at deep depths and 0˚ 0˚ 4900

therefore cannot be certain whether the separation at shallower 4700

depths continues into the MTZ. At the shallowest upper mantle −10˚ −10˚ 4500

depths, the low-velocities appear to be overall more connected than −20˚ −20˚

at the middle upper mantle and are located mostly beneath the rift

axis. In many regions, at shallow and middle upper mantle depths, −30˚ 424 km −30˚

the low-velocity anomalies are located adjacent to or between high- −30˚ −20˚ −10˚ 0˚ 10˚ 20˚ 30˚ 40˚ 50˚ 60˚

velocity features.

This pattern provides an overall sense that distinct buoyant EARS, and also in some other regions of Africa, however we note

upwellings, presumably of a thermal or thermochemical nature, that fewer upwellings were imaged beneath the less evolved southern

are rising through the upper mantle and that their paths are likely and western segments. In our view, this may be due to the history of

influenced at shallow depths by rigid, presumably lithospheric, upwellings or to the generally thicker lithosphere in the south and

structures. Ultimately, it appears that these upwellings are sourced west that may act to divert upwellings.

from MTZ depths. Such a pattern of secondary upwellings could

be sourced by a deeper, ponded anomaly at or beneath the mantle Complex upper mantle beneath Turkana

transition zone, as has been previously suggested for the EARS One region that is most suggestive of a complex upwelling and

from seismic and geochemical observations (Kieffer et al., 2004; diversion process is beneath the Turkana and South Sudan region.

Furman et al., 2006; Bastow et al., 2008; Huerta et al., 2009; Mulibo Here, the upper mantle has been difficult to image due to a lack of

and Nyblade, 2013; Civiero et al., 2015). This pattern of buoyant broadband seismic instrumentation. The Turkana segment is part of

upper mantle upwellings appears to be occurring along much of the the primary EARS focus site and is particularly unique with regards

Spring 2019 Issue No. 42 GeoPRISMS Newsletter • 7