Page 665 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 665

484 PART 4: Pulmonary Disorders

b c

Tidal volume

Volume (L) 3.0 a Tidal volume

2.5

Dynamically determined FRC

True FRC

5 Pressure (cm H 2 O)

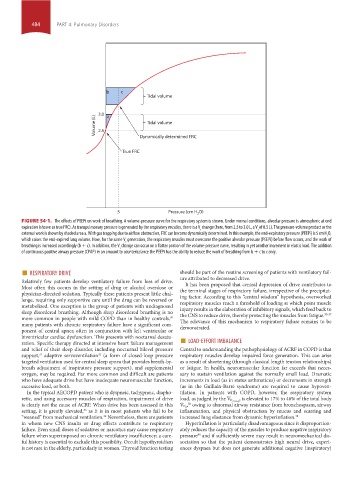

FIGURE 54-1. The effects of PEEPi on work of breathing. A volume-pressure curve for the respiratory system is shown. Under normal conditions, alveolar pressure is atmospheric at end

expiration (shown as true FRC). As transpulmonary pressure is generated by the respiratory muscles, there is a V change (here, from 2.5 to 3.0 L, a V of 0.5 L). The pressure-volume product or the

t

t

external work is shown by shaded area a. With gas trapping due to airflow obstruction, FRC can become dynamically determined. In this example, the end-expiratory pressure (PEEPi) is 5 cm H O,

2

which raises the end-expired lung volume. Now, for the same V generation, the respiratory muscles must overcome the positive alveolar pressure (PEEPi) before flow occurs, and the work of

t

breathing is increased accordingly (b + c). In addition, the V change can occur on a flatter portion of the volume-pressure curve, resulting in yet another increment in elastic load. The addition

t

of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in an amount to counterbalance the PEEPi has the ability to reduce the work of breathing from b + c to c only.

■ RESPIRATORY DRIVE should be part of the routine screening of patients with ventilatory fail-

Relatively few patients develop ventilatory failure from loss of drive. ure attributed to decreased drive.

It has been proposed that central depression of drive contributes to

Most often this occurs in the setting of drug or alcohol overdose or the terminal stages of respiratory failure, irrespective of the precipitat-

physician-directed sedation. Typically these patients present little chal-

lenge, requiring only supportive care until the drug can be reversed or ing factor. According to this “central wisdom” hypothesis, overworked

respiratory muscles reach a threshold of loading at which point muscle

metabolized. One exception is the group of patients with undiagnosed

sleep disordered breathing. Although sleep disordered breathing is no injury results in the elaboration of inhibitory signals, which feed back to

the CNS to reduce drive, thereby protecting the muscles from fatigue.

35-37

more common in people with mild COPD than in healthy controls,

30

many patients with chronic respiratory failure have a significant com- The relevance of this mechanism to respiratory failure remains to be

demonstrated.

ponent of central apnea often in conjunction with left ventricular or

ration. Specific therapy directed at intensive heart failure management ■ LOAD-EFFORT IMBALANCE

biventricular cardiac dysfunction. This presents with nocturnal desatu-

and relief of their sleep disorder, including nocturnal bilevel pressure Central to understanding the pathophysiology of ACRF in COPD is that

support, adaptive servoventilation (a form of closed-loop pressure respiratory muscles develop impaired force generation. This can arise

32

31

targeted ventilation used for central sleep apnea that provides breath-by- as a result of shortening (through classical length tension relationships)

breath adjustment of inspiratory pressure support), and supplemental or fatigue. In health, neuromuscular function far exceeds that neces-

oxygen, may be required. Far more common and difficult are patients sary to sustain ventilation against the normally small load. Dramatic

who have adequate drive but have inadequate neuromuscular function, increments in load (as in status asthmaticus) or decrements in strength

excessive load, or both. (as in the Guillain-Barré syndrome) are required to cause hypoven-

In the typical AECOPD patient who is dyspneic, tachypneic, diapho- tilation. In patients with COPD, however, the respiratory system

retic, and using accessory muscles of respiration, impairment of drive load, as judged by the V ˙ , is elevated to 17% to 46% of the total body

O 2 resp

is clearly not the cause of ACRF. When drive has been assessed in this V ˙ , owing to abnormal airway resistance from bronchospasm, airway

38

O 2

setting, it is greatly elevated, as it is in most patients who fail to be inflammation, and physical obstruction by mucus and scarring and

33

“weaned” from mechanical ventilation. Nevertheless, there are patients increased lung elastance from dynamic hyperinflation. 39

34

in whom new CNS insults or drug effects contribute to respiratory Hyperinflation is particularly disadvantageous since it disproportion-

failure. Even small doses of sedatives or narcotics may cause respiratory ately reduces the capacity of the muscles to produce negative inspiratory

failure when superimposed on chronic ventilatory insufficiency; a care- pressure and if sufficiently severe may result in neuromechanical dis-

40

ful history is essential to exclude this possibility. Occult hypothyroidism sociation so that the patient demonstrates high neural drive, experi-

is not rare in the elderly, particularly in women. Thyroid function testing ences dyspnea but does not generate additional negative (inspiratory)

section04.indd 484 1/23/2015 2:20:06 PM