Page 947 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 947

678 PART 5: Infectious Disorders

Dura Pia

Brain abscess

Osteomyelitis

Diploic veins Epidural abscess

Subdural empyema

Frontal sinus

Arachnoid meningitis

Ethmoid air cells Cavernous sinus

thrombosis

Sphenoid sinus

Maxillary sinus Pituitary Optic N.

Cavernous

Int. Carotid A. sinus

III

V 1

V 2 IV

V 3 VI

Sphenoid Intersphenoid

sinuses septum

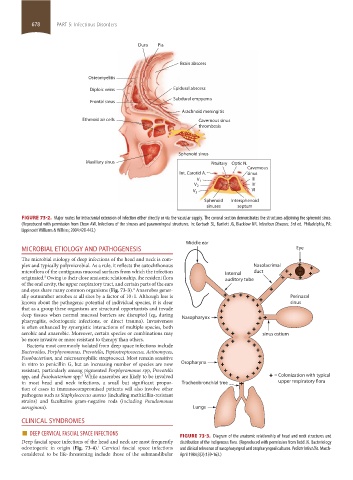

FIGURE 73-2. Major routes for intracranial extension of infection either directly or via the vascular supply. The coronal section demonstrates the structures adjoining the sphenoid sinus.

(Reproduced with permission from Chow AW. Infections of the sinuses and parameningeal structures. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:428-443.)

Middle ear

MICROBIAL ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS Eye

The microbial etiology of deep infections of the head and neck is com-

plex and typically polymicrobial. As a rule, it reflects the autochthonous Nasolacrimal

microflora of the contiguous mucosal surfaces from which the infection Internal duct

originated. Owing to their close anatomic relationship, the resident flora auditory tube

3

of the oral cavity, the upper respiratory tract, and certain parts of the ears

and eyes share many common organisms (Fig. 73-3). Anaerobes gener-

4

ally outnumber aerobes at all sites by a factor of 10 : 1. Although less is Perinasal

known about the pathogenic potential of individual species, it is clear sinus

that as a group these organisms are structural opportunists and invade

deep tissues when normal mucosal barriers are disrupted (eg, during Nasopharynx

pharyngitis, odontogenic infections, or direct trauma). Invasiveness

is often enhanced by synergistic interactions of multiple species, both

aerobic and anaerobic. Moreover, certain species or combinations may sinus ostium

be more invasive or more resistant to therapy than others.

Bacteria most commonly isolated from deep space infections include

Bacteroides, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, Actinomyces,

Fusobacterium, and microaerophilic streptococci. Most remain sensitive

in vitro to penicillin G, but an increasing number of species are now Oropharynx

resistant, particularly among pigmented Porphyromonas spp, Prevotella

spp, and Fusobacterium spp. While anaerobes are likely to be involved = Colonization with typical

5

in most head and neck infections, a small but significant propor- Tracheobronchial tree upper respiratory flora

tion of cases in immunocompromised patients will also involve other

pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant

strains) and facultative gram-negative rods (including Pseudomonas

aeruginosa). Lungs

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

■ DEEP CERVICAL FASCIAL SPACE INFECTIONS

Deep fascial space infections of the head and neck are most frequently FIGURE 73-3. Diagram of the anatomic relationship of head and neck structures and

distribution of the indigenous flora. (Reproduced with permission from Todd JK. Bacteriology

odontogenic in origin (Fig. 73-4). Cervical fascial space infections and clinical relevance of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal cultures. Pediatr Infect Dis. March-

1

considered to be life-threatening include those of the submandibular April 1984;3(2):159-163.)

section05_c61-73.indd 678 1/23/2015 12:48:56 PM