Page 949 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 949

680 PART 5: Infectious Disorders

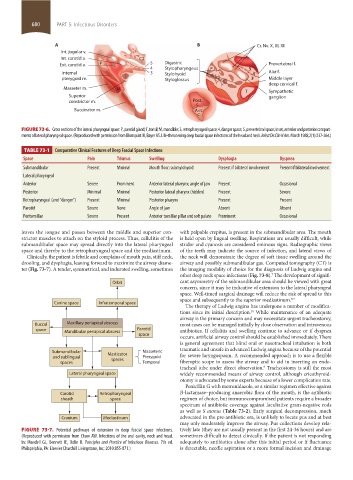

A B Cr. Nv. X, XI, XII

Int. jugular v.

Int. carotid a. C2

Ext. carotid a. P 5 Digastric Prevertebral f.

4 Stylopharyngeus P 5

Internal 3 Stylohyoid 4 Alar f.

pterygoid m. T Styloglossus 3 Middle layer

deep cervical f.

Masseter m. M T Sympathetic

Superior ganglion

constrictor m. Post.

c.

Buccinator m. Ant.

c.

FIGURE 73-6. Cross sections of the lateral pharyngeal space: P, parotid gland; T, tonsil; M, mandible; 3, retropharyngeal space; 4, danger space; 5, prevertebral space; Inset, anterior and posterior compart-

ments of lateral pharyngeal space. (Reproduced with permission from Blomquist IK, Bayer AS. Life-threatening deep fascial space infections of the head and neck. Infect Dis Clin N Am. March 1988;2(1):237-264.)

TABLE 73-1 Comparative Clinical Features of Deep Fascial Space Infections

Space Pain Trismus Swelling Dysphagia Dyspnea

Submandibular Present Minimal Mouth floor; submylohyoid Present if bilateral involvement Present if bilateral involvement

Lateral pharyngeal

Anterior Severe Prominent Anterior lateral pharynx; angle of jaw Present Occasional

Posterior Minimal Minimal Posterior lateral pharynx (hidden) Present Severe

Retropharyngeal (and “danger”) Present Minimal Posterior pharynx Present Present

Parotid Severe None Angle of jaw Absent Absent

Peritonsillar Severe Present Anterior tonsillar pillar and soft palate Prominent Occasional

leaves the tongue and passes between the middle and superior con- with palpable crepitus, is present in the submandibular area. The mouth

strictor muscles to attach on the styloid process. Thus, cellulitis of the is held open by lingual swelling. Respirations are usually difficult, while

submandibular space may spread directly into the lateral pharyngeal stridor and cyanosis are considered ominous signs. Radiographic views

space and thereby to the retropharyngeal space and the mediastinum. of the teeth may indicate the source of infection, and lateral views of

Clinically, the patient is febrile and complains of mouth pain, stiff neck, the neck will demonstrate the degree of soft tissue swelling around the

drooling, and dysphagia, leaning forward to maximize the airway diame- airway and possibly submandibular gas. Computed tomography (CT) is

ter (Fig. 73-7). A tender, symmetrical, and indurated swelling, sometimes the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of Ludwig angina and

other deep neck space infections (Fig. 73-8). The development of signifi-

7

Orbit cant asymmetry of the submandibular area should be viewed with great

concern, since it may be indicative of extension to the lateral pharyngeal

space. Well-timed surgical drainage will reduce the risk of spread to this

space and subsequently to the superior mediastinum. 8,9

Canine space Infratemporal space

The therapy of Ludwig angina has undergone a number of modifica-

tions since its initial description. While maintenance of an adequate

10

airway is the primary concern and may necessitate urgent tracheostomy,

Buccal Maxillary periapical abscess most cases can be managed initially by close observation and intravenous

space Mandibular periapical abscess Parotid antibiotics. If cellulitis and swelling continue to advance or if dyspnea

space

occurs, artificial airway control should be established immediately. There

is general agreement that blind oral or nasotracheal intubation is both

traumatic and unsafe in advanced Ludwig angina because of the potential

Submandibular Masticator Masseteric

and sublingual spaces Pterygoid for severe laryngospasm. A recommended approach is to use a flexible

spaces Temporal fiberoptic scope to assess the airway and to aid in inserting an endo-

tracheal tube under direct observation. Tracheostomy is still the most

9

Lateral pharyngeal space widely recommended means of airway control, although cricothyroid-

otomy is advocated by some experts because of a lower complication rate.

Penicillin G with metronidazole, or a similar regimen effective against

Carotid Retropharyngeal β-lactamase–producing anaerobic flora of the mouth, is the antibiotic

sheath space regimen of choice, but immunocompromised patients require a broader

spectrum of antibiotic coverage against facultative gram-negative rods

as well as S aureus (Table 73-2). Early surgical decompression, much

Cranium Mediastinum advocated in the pre-antibiotic era, is unlikely to locate pus and at best

may only moderately improve the airway. Pus collections develop rela-

FIGURE 73-7. Potential pathways of extension in deep fascial space infections. tively late (they are not usually present in the first 24-36 hours) and are

(Reproduced with permission from Chow AW. Infections of the oral cavity, neck and head. sometimes difficult to detect clinically. If the patient is not responding

In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. adequately to antibiotics alone after this initial period or if fluctuance

Philapelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, Inc; 2010:855-871.) is detectable, needle aspiration or a more formal incision and drainage

section05_c61-73.indd 680 1/23/2015 12:49:07 PM