Page 648 - Cardiac Nursing

P. 648

624 P AR T IV / Pathophysiology and Management of Heart Disease

DISPLAY 26-1 Major Indications for Intra-aortic Balloon

Pump Therapy in 16,909 Patient (1996

to 2000)

Hemodynamic support during or after cardiac

catheterization (21%)

Cardiogenic shock (19%)

Weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass (13%)

Refractory unstable angina (12%)

Refractory heart failure (6.5%)

Mechanical complications of acute myocardial

infarction (5.5%)

Intractable ventricular arrhythmias (1.7%)

invasive and allows for easy bedside removal. In all catheters, the n Figure 26-2 Percutaneous insertion of the balloon catheter

balloon is wrapped tightly around its own guide wire so that it through an introducer or sheath. Note the right wrap of the balloon.

slides easily through a sheath or directly into the artery. Once in (From Bull, S. O. [1983]. Principles and techniques of intra-aortic

balloon counterpulsation. In S. L. Woods [Ed.], Cardiovascular criti-

proper position, the balloon is inflated, resulting in unwrapping of

cal care nursing [p. 171]. New York: Churchill Livingstone.)

the balloon, allowing inflation and deflation to commence. This

catheter is secured to the skin by sutures. Figure 26-2 illustrates the

percutaneous insertion technique utilizing an introducer sheath.

A newer design (SupraCor) has recently been introduced. This decrease LV workload by lowering LV afterload. These goals are

device can be placed in the ascending aorta for use after cardiac achieved by displacement of volume in the aorta during systole

surgery. In an animal model, the device was shown to increase and diastole with alternating inflation and deflation of the bal-

blood flow in saphenous vein and internal mammary bypass loon. A typical adult-sized balloon contains 40 mL of gas or vol-

grafts, when a standardly placed IABP did not. 8 ume. For smaller adult patients, a 35-mL balloon is available; for

larger patients, a 50-mL balloon is available. Placing a smaller-

Physiologic Principles sized balloon (shorter) in smaller patients is important because a

larger (longer) balloon could extend into the abdominal aorta,

The two goals of IABP therapy are to increase coronary artery per- potentially compromising blood flow to the renal vasculature or

fusion pressure and thus coronary artery blood flow, and to even the lower extremities and exposes the balloon to abrasion

(and even rupture) from calcified abdominal aortic atherosclerotic

plaques.

The size of the catheters range from 7 to 9.5 French. When the

balloon is rapidly inflated at the onset of diastole, an additional 35

to 50 mL (depending on the balloon size) of volume is suddenly

added to the aorta. This acute increase in volume creates an early

diastolic pressure rise in the aortic root (where the coronary ostia

lie), increasing coronary artery perfusion pressure. Figure 26-3 il-

lustrates this effect. Because ischemic coronary beds are maximally

vasodilated, no further autoregulatory increases in flow are possi-

ble, and flow is pressure dependent. 9–11 IABP inflation provides

this enhanced pressure. The early diastolic pressure increase is re-

ferred to as the diastolic augmentation. Diastolic augmentation in-

creases coronary perfusion pressure and in addition, by increasing

overall mean arterial pressure, also contributes to enhanced flow

to other organs.

This augmented diastolic pressure gradually falls, as diastolic

pressure normally does when diastolic run-off occurs. Rapid evac-

uation of gas out of the balloon during deflation removes 35 to

50 mL of volume (the same amount used in inflation) out of the

aorta. This sudden drop in aortic volume rapidly decreases pres-

sure. Deflation is timed to occur at the end of diastole, just before

the patient’s next systole. Effective deflation, which decreases end-

diastolic pressure, decreases the impedance or afterload that the

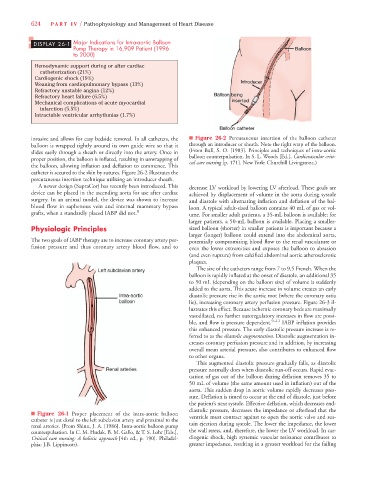

n Figure 26-1 Proper placement of the intra-aortic balloon

catheter is just distal to the left subclavian artery and proximal to the ventricle must contract against to open the aortic valve and sus-

renal arteries. (From Shinn, J. A. [1986]. Intra-aortic balloon pump tain ejection during systole. The lower the impedance, the lower

counterpulsation. In C. M. Hudak, B. M. Gallo, & T. S. Lohr [Eds.], the wall stress, and, therefore, the lower the LV workload. In car-

Critical care nursing: A holistic approach [4th ed., p. 190]. Philadel- diogenic shock, high systemic vascular resistance contributes to

phia: J.B. Lippincott). greater impedance, resulting in a greater workload for the failing