Page 69 - Hematology_ Basic Principles and Practice ( PDFDrive )

P. 69

Chapter 4 Regulation of Gene Expression, Transcription, Splicing, and RNA Metabolism 41

Exon Intron Exon mRNA

-AAAAAAAAA

5 - -3

snRNPs Nucleus Nuclear

filamentous

proteins

5 - -3 Nuclear

basket

Spliceosome

DNA

lariat

Nuclear Central

envelope core channel

5 - -3

Mature mRNA

Fig. 4.4 RNA SPLICING. Introns from pre-mRNA are removed by snRNPs, Cytoplasm Cytosolic

which form a protein complex called a spliceosome. The spliceosome loops filamentous

introns into a lariat, excises them, and then joins exons. The mature mRNA proteins

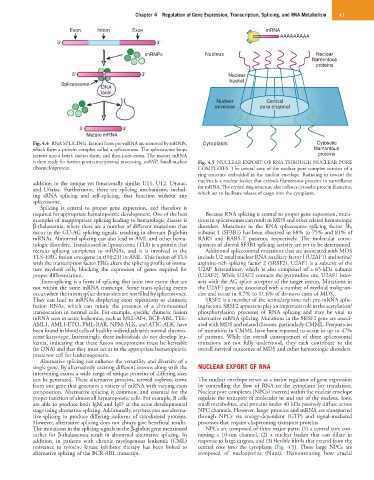

is then ready for further posttranscriptional processing. snRNP, Small nuclear Fig. 4.5 NUCLEAR EXPORT OF RNA THROUGH NUCLEAR PORE

ribonucleoprotein. COMPLEXES. The central core of the nuclear pore complex consists of a

ring structure embedded in the nuclear envelope. Radiating in toward the

nucleus is a nuclear basket that extends filamentous proteins in surveillance

addition to the unique yet functionally similar U11, U12, U4atac,

and U6atac. Furthermore, there are splicing mechanisms, includ- for mRNA. The central ring structure also radiates cytosolic protein filaments,

ing tRNA splicing and self-splicing, that function without any which act to facilitate release of cargo into the cytoplasm.

spliceosome.

Splicing is central to proper gene expression, and therefore is

required for appropriate hematopoietic development. One of the best Because RNA splicing is central to proper gene expression, muta-

examples of inappropriate splicing leading to hematologic disease is tions in spliceosomes can result in MDS and other related hematologic

β-thalassemia, where there are a number of different mutations that disorders. Mutations in the RNA spliceosome splicing factor 3b,

occur in the GU-AG splicing signals, resulting in aberrant β-globin subunit 1 (SF3B1) has been observed in 68% to 75% and 81% of

mRNAs. Abnormal splicing can also lead to AML and other hema- RARS and RARS-T patients, respectively. The molecular conse-

tologic disorders. Translocated in liposarcoma (TLS) is a protein that quences of altered SF3B1 splicing activity are yet to be determined.

recruits splicing complexes to mRNAs, and it is involved in the Additional spliceosomal mutations that are associated with MDS

TLS–ERG fusion oncogene in t(16;21) in AML. This fusion of TLS include U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor I (U2AF1) and serine/

with the transcription factor ERG alters the splicing profile of imma- arginine-rich splicing factor 2 (SRSF2). U2AF1 is a subunit of the

ture myeloid cells, blocking the expression of genes required for U2AF heterodimer, which is also composed of a 65-kDa subunit

proper differentiation. (U2AF2). While U2AF2 contacts the pyrimidine site, U2AF1 inter-

Trans-splicing is a form of splicing that joins two exons that are acts with the AG splice acceptor of the target intron. Mutations in

not within the same mRNA transcript. Some trans-splicing events the U2AF1 gene are associated with a number of myeloid malignan-

occur when the intron splice donor sites are not filled by spliceosomes. cies and occur in 8.7% to 11.6% of de-novo cases of MDS.

They can lead to mRNAs displaying exon repetitions or chimeric SRSF2 is a member of the serine/arginine-rich pre-mRNA splic-

fusion RNAs, which can mimic the presence of a chromosomal ing factors. SRSF2 appears to play an important role in the acetylation/

translocation in normal cells. For example, specific chimeric fusion phosphorylation processes of RNA splicing and may be vital to

mRNA seen in acute leukemias, such as MLL-AF4, BCR-ABL, TEL- alternative mRNA splicing. Mutations in the SRSF2 gene are associ-

AML1, AML1-ETO, PML-RAR, NPM-ALK, and ATIC-ALK, have ated with MDS and related diseases, particularly CMML. Frequencies

been found in blood cells of healthy individuals with normal chromo- of mutations in CMML have been reported to occur in up to 47%

some karyotype. Interestingly, these individuals do not develop leu- of patients. While the overall consequences of these spliceosomal

kemia, indicating that these fusion oncoproteins must be heritable mutations are not fully understood, they each contribute to the

(in DNA) and that they must occur in the appropriate hematopoietic overall survival outcomes of MDS and other hematologic disorders.

precursor cell for leukemogenesis.

Alternative splicing can enhance the versatility and diversity of a

single gene. By alternatively excising different introns along with the NUCLEAR EXPORT OF RNA

intervening exons, a wide range of unique proteins of differing sizes

can be generated. These alternative proteins, termed isoforms, come The nuclear envelope serves as a major regulator of gene expression

from one gene that generates a variety of mRNA with varying exon by controlling the flow of RNA to the cytoplasm for translation.

composition. Alternative splicing is common, and essential for the Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) inserted within the nuclear envelope

proper function of almost all hematopoietic cells. For example, B cells regulate the transport of molecules in and out of the nucleus. Ions,

are able to produce both IgM and IgD at the same developmental small metabolites, and proteins under 40 kDa passively diffuse across

stage using alternative splicing. Additionally, erythrocytes use alterna- NPC channels. However, larger proteins and mRNA are transported

tive splicing to produce differing isoforms of cytoskeletal proteins. through NPCs via energy-dependent (GTP) and signal-mediated

However, alternative splicing does not always give beneficial results. processes that require chaperoning transport proteins.

The mutations in the splicing signals in the β-globin gene mentioned NPCs are composed of three major parts: (1) a central core con-

earlier for β-thalassemia result in abnormal alternative splicing. In taining a 10-nm channel, (2) a nuclear basket that can dilate in

addition, in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) response to large cargoes, and (3) flexible fibrils that extend from the

resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy has been linked to central core into the cytoplasm (Fig. 4.5). These large NPCs are

alternative splicing of the BCR-ABL transcript. composed of nucleoporins (Nups). Demonstrating how crucial