Page 272 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 272

176 PART 2: General Management of the Patient

after resuscitation from cardiac arrest, as measured at autopsy in Intra-arrest Postarrest

patients who died within days of undergoing resuscitative measures.

44

Widespread evidence from animals also supports the notion that apop- 1 3

tosis is activated after reperfusion. 25,45 Hypothermia may inhibit this

process. Proteolysis of the cytoskeletal protein fodrin, a characteristic No-flow

step in the apoptotic pathway, is inhibited by hypothermia to 32°C in a Intra-arrest

rat brain IR model. The process of apoptosis is an active one, requiring low flow

46

protein synthesis and enzymatic activity, both of which may be inhibited Cardiac cooling ROSC or

by lower temperatures. While some data suggest that the degree of apop- Blood arrest bypass

tosis can be reduced by hypothermia, the topic certainly deserves more flow 2

investigation in animal models.

CPR

HYPOTHERMIA IN CARDIAC ARREST

Cardiac arrest is a highly mortal condition that leads to at least 300,000

deaths each year in the United States alone. Survival from cardiac arrest

47

remains dismal some 50 years after introduction of chest compressions Time

and electrical defibrillation, with only 1% to 11% of patients surviving FIGURE 26-3. Time periods during which hypothermia may be used during an ischemia-

until hospital discharge after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. 48-50 While reperfusion injury such as cardiac arrest or myocardial infaction.

initial survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest ranges from 25% to over

50%, subsequent survival until hospital discharge is much lower, from

5% to 22%, suggesting that a high mortality rate is seen shortly after ini- or clinical potential of such hypothermia owing in large part to the tech-

tial ROSC. Some of this mortality after return of normal circulation may nical difficulties involved in inducing hypothermia during the low-flow

be due to events related to reperfusion injury (see Fig. 26-2). For further states of sudden cardiac arrest.

discussion of cardiac arrest and resuscitation therapies, see Chap. 25. The 2010 Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) guidelines strongly

Cardiac arrest remains a major medical challenge despite research recommend cooling out-of-hospital (OOH) ventricular fibrillation or

efforts over the past few decades. There is little time after arrest to pulseless ventricular tachycardic postarrest patients who remain coma-

defibrillate the heart and thereby stop ongoing ischemic injury to key tose. The guidelines for in-hospital and OOH nonshockable rhythm

52

organs such as the heart and brain. Few therapies are proven to be useful arrests encourage providers to consider this therapy for these patients.

during the postresuscitation phase of cardiac arrest—when up to 90% of See Table 26-1 for sample exclusion criteria. It is recommended that

patients go on to die despite successful defibrillation. New approaches ICU physicians and staff establish protocols for cooling after cardiac

are desperately needed to improve cardiac arrest survival, and induced arrest. Development of such protocols will require consideration of a

hypothermia may be one of the most promising new approaches. 51 number of hospital-specific technical issues (eg, how to cool, who will

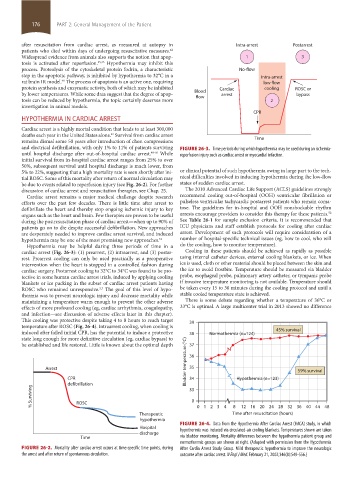

Hypothermia may be helpful during three periods of time in a do the cooling, how to monitor temperature).

cardiac arrest (Fig. 26-3): (1) prearrest, (2) intraarrest, and (3) postar- Cooling in these patients should be achieved as rapidly as possible

rest. Prearrest cooling can only be used practically as a preoperative using internal catheter devices, external cooling blankets, or ice. When

intervention when the heart is stopped in a controlled fashion during ice is used, cloth or other material should be placed between the skin and

cardiac surgery. Postarrest cooling to 32°C to 34°C was found to be pro- the ice to avoid frostbite. Temperature should be measured via bladder

tective in some human cardiac arrest trials, induced by applying cooling probe, esophageal probe, pulmonary artery catheter, or tympanic probe

blankets or ice packing in the subset of cardiac arrest patients having if invasive temperature monitoring is not available. Temperature should

ROSC who remained unresponsive. The goal of this level of hypo- be taken every 15 to 30 minutes during the cooling protocol and until a

2,3

thermia was to prevent neurologic injury and decrease mortality while stable cooled temperature state is achieved.

maintaining a temperature warm enough to prevent the other adverse There is some debate regarding whether a temperature of 36°C or

effects of more profound cooling (eg, cardiac arrhythmia, coagulopathy, 33°C is optimal. A large multicenter trial in 2013 showed no difference

and infection—see discussion of adverse effects later in this chapter).

This cooling was protective despite taking 4 to 8 hours to reach target 39

temperature after ROSC (Fig. 26-4). Intraarrest cooling, when cooling is

induced after failed initial CPR, has the potential to induce a protective 38 Normothermia (n=124) 45% survival

state long enough for more definitive circulation (eg, cardiac bypass) to

be established and life restored. Little is known about the optimal depth 37

36

Arrest Bladder temperature (°C) 35 59% survival

CPR 34 Hypothermia (n=123)

defibrillation 33

% Surviving ROSC 0

1216 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48

8

Therapeutic 0 1 2 34 Time after resuscitation (hours)

hypothermia

FIGURE 26-4. Data from the Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest (HACA) study, in which

Hospital hypothermia was induced via circulated-air cooling blankets. Temperatures shown are taken

discharge

Time via bladder monitoring. Mortality differences between the hypothermia patient group and

normothermic groups are shown at right. (Adapted with permission from the Hypothermia

FIGURE 26-2. Mortality after cardiac arrest occurs at time-specific time points, during After Cardia Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic

the arrest and after return of spontaneous circulation. outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. February 21, 2002;346(8):549-556.)

section02.indd 176 1/13/2015 2:05:15 PM