Page 54 - Hematology_ Basic Principles and Practice ( PDFDrive )

P. 54

26 Part I Molecular and Cellular Basis of Hematology

heterogeneity involves analyzing cells at the single-cell level, as all of these methods identify major associations within a given dataset

described later. if the signature is strong and robust. Great care must be taken in the

At the level of DNA analysis (as opposed to RNA analysis), the interpretation of clustering results because clusters with distinct gene

admixture of nonmalignant cells within a tumor may not obscure the expression profiles may be caused not only by biologically important

presence of mutations in the tumor cells, even if those cells represent distinctions but also by artefacts of sample processing. Unsupervised

a minority population. However, the detection of mutations in a learning methods that have been used include hierarchical clustering,

subset of cells within a sample requires extra depth of sequencing principal component analysis, nonnegative matrix factorization, k-

beyond what would be required to sequence, for example, a normal means clustering, and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

diploid genome. Thus it becomes critical to have a rough estimate of Supervised learning approaches are best suited for comparing data

the purity of a given sample so that the appropriate genomic approach between two or more classes of samples that can be distinguished by

can be used subsequently. some known property (or class distinction), such as biologic subtype

or clinical outcome. For example, to determine the gene expression

differences between different leukemia subtypes with distinct genetic

Analytical Considerations abnormalities, one would use a supervised approach (Fig. 3.1). The

same genes might be clustered together on the basis of unsupervised

Unsupervised learning approaches (often referred to as clustering) approaches already described, but they might also be obscured by a

have become an important part of the discovery process in genomic more dominant gene expression signature that is unrelated to the

analysis. This type of analysis involves grouping samples solely on the distinction of interest. For example, if there were another major

basis of data obtained without regard to any prior knowledge of the signature within the data (i.e., a stage of differentiation signature),

samples or the disease. Thus one can obtain the predominant “struc- the differences that the investigator was searching for might be lost.

ture” of the dataset without imposing any prior bias. For example, A number of metrics can be used to identify genes that are differen-

unsupervised learning approaches have been used to cluster leukemia tially expressed between two groups of samples, all of which are best

or lymphoma samples on the basis of their gene expression profiles suited to identification of genes that are uniformly highly expressed

with the goal of uncovering the most robust classification schemes. in one group. Although the different metrics may generate slightly

Clustering algorithms can also cluster genes that have a similar expres- different lists of gene expression differences, if the gene expression

sion profile in a gene expression dataset. There are a number of difference is robust, all should give comparable results.

methods for clustering genes and samples, all of which have compu- With the ability to generate large-scale genomic datasets come

tational strengths and weaknesses. Comparison of the clustering a number of analytical issues that are unique to what has come to

methods is beyond the scope of this chapter, but suffice it to say that be known as “big data.” In particular, when the number of features

ALL MLL AML

J03779 MME (CD10)

L33930 CD24

Y12735 DYRK3

M11722 DNTT (TDT)

X83441 LIG4 (DNA Ligase IV)

AF032885 FOXO1A (FKHR)

M96803 SPTBN1 (Spectrum-β)

AB020674 KIAA0867

X59350 CD22

Z49194 POU2AF1(OBF-1)

AL049279 DKFZp5641083

U48959 MYLK (MLCK)

U29175 SMARCA4 (SNF2-β)

AF054825 VAMP5

A1761647 cDNA wg66h09

U02687 FLT3

AB007888 KIAA0428

AJ001687 NKG2D

AF009615 ADAM10

AF027208 PROML1 (AC133)

U02687 FLT3

AB028948 KIAA1025

AI535946 LGALS1 Galectin 1)

U66838 CCNA1 (Cyclin A1)

AL050157 DKFZp586o0120

Z48579 ADAM10

AF026816 ITPA (Inosine triphosphatase)

AA669799 cDNA ag36c04

AB023137 KIAA0920

X61118 LMO2

X04325 GJB1

X64364 BSG

X99906 ENSA (α-endosulfine)

M63138 CTSD (CathepsinD)

M84526 DF (Adipsin)

U35117 TFDP2

U41843 DRAP1

L27066 NF2

W27095 cDNA 20c10

Y08134 PDE3B (Phosphodiesterase 3B)

M22324 ANPEP (CD13)

AC005787 Chromosome 19 clone

DB7002 Chromosome 22q11 clone

AF004222 RTN2

U05569 CRYAA

-3σ -2σ -1σ 0 +1σ +2σ +3σ

σ = standard deviation from mean

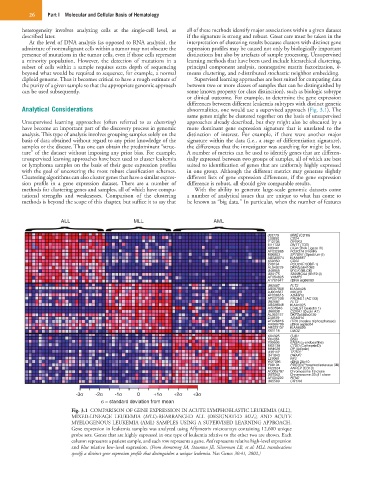

Fig. 3.1 COMPARISON OF GENE EXPRESSION IN ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKEMIA (ALL),

MIXED-LINEAGE LEUKEMIA (MLL)-REARRANGED ALL (DESIGNATED MLL), AND ACUTE

MYELOGENOUS LEUKEMIA (AML) SAMPLES USING A SUPERVISED LEARNING APPROACH.

Gene expression in leukemia samples was analyzed using Affymetrix microarrays containing 12,600 unique

probe sets. Genes that are highly expressed in one type of leukemia relative to the other two are shown. Each

column represents a patient sample, and each row represents a gene. Red represents relative high-level expression

and blue relative low-level expression. (From Armstrong SA, Staunton JE, Silverman LB, et al: MLL translocations

specify a distinct gene expression profile that distinguishes a unique leukemia. Nat Genet 30:41, 2002.)