Page 57 - Hematology_ Basic Principles and Practice ( PDFDrive )

P. 57

Chapter 3 Genomic Approaches to Hematology 29

TUMOR

NORMAL

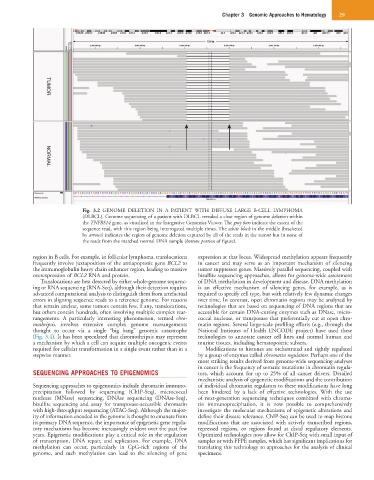

Fig. 3.2 GENOME DELETION IN A PATIENT WITH DIFFUSE LARGE B-CELL LYMPHOMA

(DLBCL). Genome sequencing of a patient with DLBCL revealed a clear region of genome deletion within

the TNFRS14 gene, as visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer. The gray bars indicate the extent of the

sequence read, with this region being interrogated multiple times. The white block in the middle (bracketed

by arrows) indicates the region of genome deletion captured by all of the reads in the tumor but in none of

the reads from the matched normal DNA sample (bottom portion of figure).

region in B cells. For example, in follicular lymphoma, translocations expression at that locus. Widespread methylation appears frequently

frequently involve juxtaposition of the antiapoptotic gene BCL2 to in cancer and may serve as an important mechanism of silencing

the immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer region, leading to massive tumor suppressor genes. Massively parallel sequencing, coupled with

overexpression of BCL2 RNA and protein. bisulfite sequencing approaches, allows for genome-wide assessment

Translocations are best detected by either whole-genome sequenc- of DNA methylation in development and disease. DNA methylation

ing or RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), although their detection requires is an effective mechanism of silencing genes, for example, as is

advanced computational analysis to distinguish them from artefactual required to specify cell type, but with relatively few dynamic changes

errors in aligning sequence reads to a reference genome. For reasons over time. In contrast, open chromatin regions may be analyzed by

that remain unclear, some tumors contain few, if any, translocations, technologies that are based on sequencing of DNA regions that are

but others contain hundreds, often involving multiple complex rear- accessible for certain DNA-cutting enzymes such as DNase, micro-

rangements. A particularly interesting phenomenon, termed chro- coccal nuclease, or transposase that preferentially cut at open chro-

mothripsis, involves extensive complex genome rearrangements matin regions. Several large-scale profiling efforts (e.g., through the

thought to occur via a single “big bang” genomic catastrophe National Institutes of Health ENCODE project) have used these

(Fig. 3.4). It has been speculated that chromothripsis may represent technologies to annotate cancer cell lines and normal human and

a mechanism by which a cell can acquire multiple oncogenic events murine tissues, including hematopoietic subsets.

required for cellular transformation in a single event rather than in a Modifications to histones are orchestrated and tightly regulated

stepwise manner. by a group of enzymes called chromatin regulators. Perhaps one of the

most striking results derived from genome-wide sequencing analyses

in cancer is the frequency of somatic mutations in chromatin regula-

SEQUENCING APPROACHES TO EPIGENOMICS tors, which account for up to 25% of all cancer drivers. Detailed

mechanistic analysis of epigenetic modifications and the contribution

Sequencing approaches to epigenomics include chromatin immuno- of individual chromatin regulators to these modifications have long

precipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-Seq), micrococcal been hindered by a lack of effective technologies. With the use

nuclease (MNase) sequencing, DNAse sequencing (DNAse-Seq), of next-generation sequencing techniques combined with chroma-

bisulfite sequencing and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin tin immunoprecipitation, it is now possible to comprehensively

with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-Seq). Although the major- investigate the molecular mechanisms of epigenetic alterations and

ity of information encoded in the genome is thought to emanate from define their disease relevance. ChIP-Seq can be used to map histone

its primary DNA sequence, the importance of epigenetic gene regula- modifications that are associated with actively transcribed regions,

tory mechanisms has become increasingly evident over the past few repressed regions, or regions found at distal regulatory elements.

years. Epigenetic modifications play a critical role in the regulation Optimized technologies now allow for ChIP-Seq with small input of

of transcription, DNA repair, and replication. For example, DNA samples or with FFPE samples, which has significant implications for

methylation can occur, particularly in CpG-rich regions of the translating this technology to approaches for the analysis of clinical

genome, and such methylation can lead to the silencing of gene specimens.