Page 231 - Clinical Immunology_ Principles and Practice ( PDFDrive )

P. 231

210 Part One Principles of Immune Response

Dendritic cell

Intraepithelial Bacteria Antimicrobial

Dendritic cell lymphocyte peptides

Lumen

MAMPs Dimeric IgA

Goblet cell

M cell T cell IgA+ cell

Epithelium

B cell

Lamina

propria Cryptopatch

Peyer’s patch

Paneth cell

LTi cell Mature isolated Peyer’s patch

Mesenteric lymphoid follicle

lymph node

A Prenatal B Postnatal

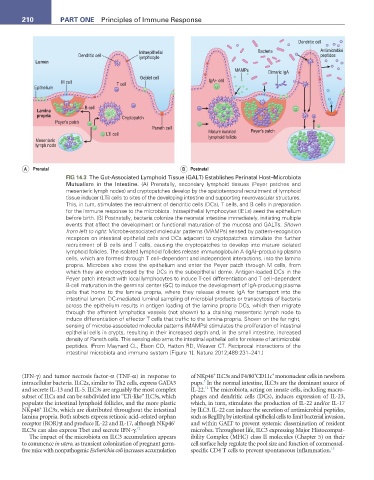

FIG 14.3 The Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) Establishes Perinatal Host–Microbiota

Mutualism in the Intestine. (A) Prenatally, secondary lymphoid tissues (Peyer patches and

mesenteric lymph nodes) and cryptopatches develop by the spatiotemporal recruitment of lymphoid

tissue inducer (LTi) cells to sites of the developing intestine and supporting neurovascular structures.

This, in turn, stimulates the recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, and B cells in preparation

for the immune response to the microbiota. Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) seed the epithelium

before birth. (B) Postnatally, bacteria colonize the neonatal intestine immediately, initiating multiple

events that affect the development or functional maturation of the mucosa and GALTs. Shown

from left to right: Microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) sensed by pattern-recognition

receptors on intestinal epithelial cells and DCs adjacent to cryptopatches stimulate the further

recruitment of B cells and T cells, causing the cryptopatches to develop into mature isolated

lymphoid follicles. The isolated lymphoid follicles release immunoglobulin A (IgA)–producing plasma

cells, which are formed through T cell–dependent and independent interactions, into the lamina

propria. Microbes also cross the epithelium and enter the Peyer patch through M cells, from

which they are endocytosed by the DCs in the subepithelial dome. Antigen-loaded DCs in the

Peyer patch interact with local lymphocytes to induce T-cell differentiation and T cell–dependent

B-cell maturation in the germinal center (GC) to induce the development of IgA-producing plasma

cells that home to the lamina propria, where they release dimeric IgA for transport into the

intestinal lumen. DC-mediated luminal sampling of microbial products or transcytosis of bacteria

across the epithelium results in antigen loading of the lamina propria DCs, which then migrate

through the afferent lymphatics vessels (not shown) to a draining mesenteric lymph node to

induce differentiation of effector T cells that traffic to the lamina propria. Shown on the far right,

sensing of microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) stimulates the proliferation of intestinal

epithelial cells in crypts, resulting in their increased depth and, in the small intestine, increased

density of Paneth cells. This sensing also arms the intestinal epithelial cells for release of antimicrobial

peptides. (From Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Reciprocal interactions of the

intestinal microbiota and immune system [Figure 1]. Nature 2012;489:231–241.)

+

+

+

(IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in response to of NKp46 ILC3s and F4/80 CD11c mononuclear cells in newborn

3

intracellular bacteria. ILC2s, similar to Th2 cells, express GATA3 pups. In the normal intestine, ILC3s are the dominant source of

12

and secrete IL-13 and IL-5. ILC3s are arguably the most complex IL-22. The microbiota, acting on innate cells, including macro-

subset of ILCs and can be subdivided into “LTi-like” ILC3s, which phages and dendritic cells (DCs), induces expression of IL-23,

populate the intestinal lymphoid follicles, and the more plastic which, in turn, stimulates the production of IL-22 and/or IL-17

+

NKp46 ILC3s, which are distributed throughout the intestinal by ILC3. IL-22 can induce the secretion of antimicrobial peptides,

lamina propria. Both subsets express retinoic acid–related orphan such as RegIIIγ, by intestinal epithelial cells to limit bacterial invasion,

+

receptor (ROR)γt and produce IL-22 and IL-17, although NKp46 and within GALT to prevent systemic dissemination of resident

ILC3s can also express Tbet and secrete IFN-γ. 12 microbes. Throughout life, ILC3 expressing Major Histocompat-

The impact of the microbiota on ILC3 accumulation appears ibility Complex (MHC) class II molecules (Chapter 5) on their

to commence in utero, as transient colonization of pregnant germ- cell surface help regulate the pool size and function of commensal-

free mice with nonpathogenic Escherichia coli increases accumulation specific CD4 T cells to prevent spontaneous inflammation. 13