Page 330 - Clinical Immunology_ Principles and Practice ( PDFDrive )

P. 330

310 Part two Host Defense Mechanisms and Inflammation

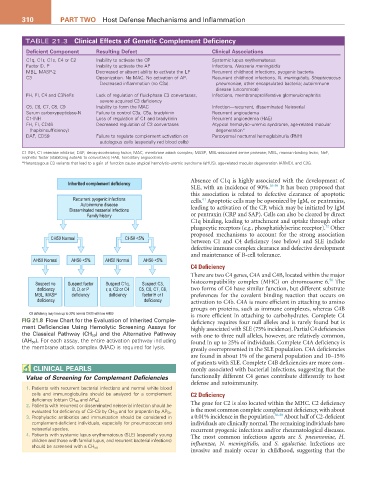

TABLE 21.3 Clinical Effects of Genetic Complement Deficiency

Deficient Component resulting Defect Clinical associations

C1q, C1r, C1s, C4 or C2 Inability to activate the CP Systemic lupus erythematosus

Factor D, P Inability to activate the AP Infections, Neisseria meningitidis

MBL, MASP-2 Decreased or absent ability to activate the LP Recurrent childhood infections, pyogenic bacteria

C3 Opsonization. No MAC. No activation of AP. Recurrent childhood infections, N. meningitidis, Streptococcus

Decreased inflammation (no C3a). pneumoniae, other encapsulated bacteria; autoimmune

disease (uncommon)

FH, FI, C4 and C3NeFs Lack of regulation of fluid-phase C3 convertases, Infections, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

severe acquired C3 deficiency

C5, C6, C7, C8, C9 Inability to form the MAC Infection—recurrent, disseminated Neisserial

Serum carboxypeptidase-N Failure to control C3a, C5a, bradykinin Recurrent angioedema

C1-INH Loss of regulation of C1 and bradykinin Recurrent angioedema (HAE)

FH, FI, CD46 Decreased regulation of C3 convertases Atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome, age-related macular

(haploinsufficiency) degeneration*

DAF, CD59 Failure to regulate complement activation on Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)

autologous cells (especially red blood cells)

C1 INH, C1 esterase inhibitor; DAF, decay-accelerating factor; MAC, membrane attack complex; MASP, MBL-associated serine protease; MBL, mannan-binding lectin; NeF,

nephritic factor (stabilizing autoAb to convertase); HAE, hereditary angioedema.

*Heterozygous C3 variants that lead to a gain of function cause atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome (aHUS), age-related macular degeneration (ARMD), and C3G.

Absence of C1q is highly associated with the development of

Inherited complement deficiency 56-59

SLE, with an incidence of 90%. It has been proposed that

this association is related to defective clearance of apoptotic

Recurrent pyogenic infections cells. Apoptotic cells may be opsonized by IgM, or pentraxins,

61

Autoimmune disease

Disseminated nesserial infections leading to activation of the CP, which may be initiated by IgM

Family history or pentraxin (CRP and SAP). Cells can also be cleared by direct

C1q binding, leading to attachment and uptake through other

52

phagocytic receptors (e.g., phosphatidylserine receptor). Other

proposed mechanisms to account for the strong association

CH50 Normal CH50 <5%

between C1 and C4 deficiency (see below) and SLE include

defective immune complex clearance and defective development

and maintenance of B-cell tolerance.

AH50 Normal AH50 <5% AH50 Normal AH50 <5%

C4 Deficiency

There are two C4 genes, C4A and C4B, located within the major

58

Suspect no Suspect factor Suspect C1q, Suspect C3, histocompatibility complex (MHC) on chromosome 6. The

deficiency B, D, or P r, s, C2 or C4 C5, C6, C7, C8, two forms of C4 have similar function, but different substrate

MBL, MASP deficiency deficiency factor H or I preferences for the covalent binding reaction that occurs on

deficiency deficiency activation to C4b. C4A is more efficient in attaching to amino

groups on proteins, such as immune complexes, whereas C4B

C9 deficiency may have up to 30% normal CH50 with low AH50 is more efficient in attaching to carbohydrates. Complete C4

FIG 21.8 Flow Chart for the Evaluation of Inherited Comple- deficiency requires four null alleles and is rarely found but is

ment Deficiencies Using Hemolytic Screening Assays for highly associated with SLE (75% incidence). Partial C4 deficiencies

the Classical Pathway (CH 50) and the Alternative Pathway with one to three null alleles, however, are relatively common,

(AH 50 ). For each assay, the entire activation pathway including found in up to 25% of individuals. Complete C4A deficiency is

the membrane attack complex (MAC) is required for lysis. greatly overrepresented in the SLE population. C4A deficiencies

are found in about 1% of the general population and 10–15%

of patients with SLE. Complete C4B deficiencies are more com-

CLINICaL PEarLS monly associated with bacterial infections, suggesting that the

Value of Screening for Complement Deficiencies functionally different C4 genes contribute differently to host

defense and autoimmunity.

1. Patients with recurrent bacterial infections and normal white blood

cells and immunoglobulins should be analyzed for a complement C2 Deficiency

deficiency (obtain CH 50 and AP 50 ).

2. Patients with recurrent or disseminated neisserial infection should be The gene for C2 is also located within the MHC. C2 deficiency

evaluated for deficiency of C3–C9 by CH 50 and for properdin by AP 50 . is the most common complete complement deficiency, with about

3. Prophylactic antibiotics and immunization should be considered in a 0.01% incidence in the population. 56-58 About half of C2-deficient

complement-deficient individuals, especially for pneumococcus and individuals are clinically normal. The remaining individuals have

neisserial species. recurrent pyogenic infections and/or rheumatological diseases.

4. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (especially young The most common infectious agents are S. pneumoniae, H.

children and those with familial lupus, and recurrent bacterial infections)

influenzae, N. meningitidis, and S. agalactiae. Infections are

should be screened with a CH 50.

invasive and mainly occur in childhood, suggesting that the