Page 296 - (DK) Ocean - The Definitive Visual Guide

P. 296

294 ANIMAL LIFE

SUBPHYLUM CRUSTACEA SUBPHYLUM CRUSTACEA

Cyclopoid Copepod Gooseneck Barnacle

Oithona similis Pollicipes polymerus

LENGTH LENGTH

3

1 / 54– / 32 in (0.5–2.5 mm)

Up to 3 in (8 cm)

HABITAT HABITAT

Surface waters to a Intertidal zone of rocky

depth of 500 ft (150 m) shores

DISTRIBUTION Atlantic, Mediterranean, Southern DISTRIBUTION Eastern Pacific coast of North

Ocean, southern Indian and Pacific oceans America, from Canada to Baja California, Mexico

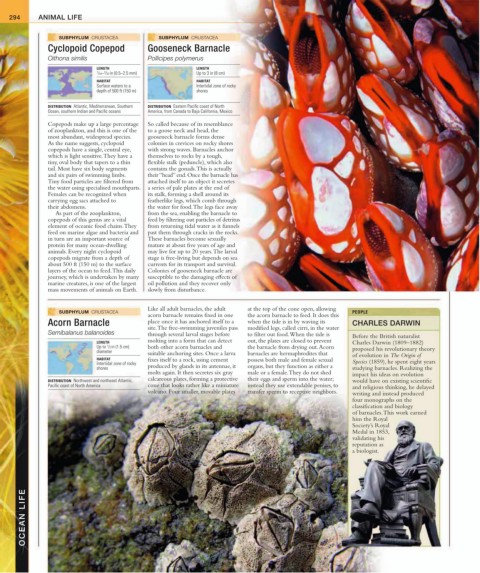

Copepods make up a large percentage So called because of its resemblance

of zooplankton, and this is one of the to a goose neck and head, the

most abundant, widespread species. gooseneck barnacle forms dense

As the name suggests, cyclopoid colonies in crevices on rocky shores

copepods have a single, central eye, with strong waves. Barnacles anchor

which is light sensitive. They have a themselves to rocks by a tough,

tiny, oval body that tapers to a thin flexible stalk (peduncle), which also

tail. Most have six body segments contains the gonads. This is actually

and six pairs of swimming limbs. their “head” end. Once the barnacle has

Tiny food particles are filtered from attached itself to an object it secretes

the water using specialised mouthparts. a series of pale plates at the end of

Females can be recognized when its stalk, forming a shell around its

carrying egg sacs attached to featherlike legs, which comb through

their abdomens. the water for food. The legs face away

As part of the zooplankton, from the sea, enabling the barnacle to

copepods of this genus are a vital feed by filtering out particles of detritus

element of oceanic food chains. They from returning tidal water as it funnels

feed on marine algae and bacteria and past them through cracks in the rocks.

in turn are an important source of These barnacles become sexually

protein for many ocean-dwelling mature at about five years of age and

animals. Every night cyclopoid may live for up to 20 years. The larval

copepods migrate from a depth of stage is free-living but depends on sea

about 500 ft (150 m) to the surface currents for its transport and survival.

layers of the ocean to feed. This daily Colonies of gooseneck barnacle are

journey, which is undertaken by many susceptible to the damaging effects of

marine creatures, is one of the largest oil pollution and they recover only

mass movements of animals on Earth. slowly from disturbance.

Like all adult barnacles, the adult at the top of the cone open, allowing

SUBPHYLUM CRUSTACEA PEOPLE

acorn barnacle remains fixed in one the acorn barnacle to feed. It does this

Acorn Barnacle place once it has anchored itself to a when the tide is in by waving its CHARLES DARWIN

site. The free-swimming juveniles pass modified legs, called cirri, in the water

through several larval stages before

Semibalanus balanoides to filter out food. When the tide is Before the British naturalist

LENGTH molting into a form that can detect out, the plates are closed to prevent Charles Darwin (1809–1882)

1

Up to / 2 in (1.5 cm) both other acorn barnacles and the barnacle from drying out. Acorn proposed his revolutionary theory

diameter suitable anchoring sites. Once a larva barnacles are hermaphrodites that

HABITAT fixes itself to a rock, using cement possess both male and female sexual of evolution in The Origin of

Intertidal zone of rocky Species (1859), he spent eight years

shores produced by glands in its antennae, it organs, but they function as either a studying barnacles. Realizing the

molts again. It then secretes six gray male or a female. They do not shed impact his ideas on evolution

DISTRIBUTION Northwest and northeast Atlantic, calcareous plates, forming a protective their eggs and sperm into the water; would have on existing scientific

Pacific coast of North America cone that looks rather like a miniature instead they use extendable penises, to and religious thinking, he delayed

volcano. Four smaller, movable plates transfer sperm to receptive neighbors. writing and instead produced

four monographs on the

classification and biology

of barnacles. This work earned

him the Royal

Society’s Royal

Medal in 1853,

validating his

reputation as

a biologist.

OCEAN LIFE