Page 347 - Basic Principles of Textile Coloration

P. 347

336 REACTIVE DYES

Cl Cl F

NN NN NN

Dye NH N Cl Dye NH N NHR Dye NH N NHR

Dichlorotriazine (DCT) Monochlorotriazine (MCT) Monofluorotriazine (MFT)

NHR CO2H Cl N Cl

NN Cl

Dye NH N N

N

Nicotinyltriazine (NT)

Dye NH N Cl Dye CO N Cl

Trichloropyrimidine (TCP) Dichloroquinoxaline (DCQ)

F Dye SO2 CH CH2

Cl Vinylsulphone (VS)

N

Dye NH N F

Difluorochloropyrimidine (DFCP)

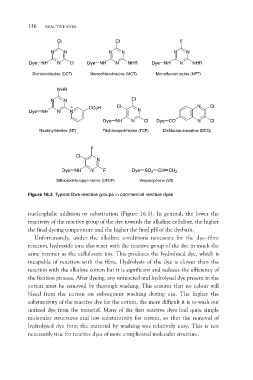

Figure 16.3 Typical fibre-reactive groups in commercial reactive dyes

nucleophilic addition or substitution (Figure 16.1). In general, the lower the

reactivity of the reactive group of the dye towards the alkaline cellulose, the higher

the final dyeing temperature and the higher the final pH of the dyebath.

Unfortunately, under the alkaline conditions necessary for the dye–fibre

reaction, hydroxide ions also react with the reactive group of the dye in much the

same manner as the cellulosate ion. This produces the hydrolysed dye, which is

incapable of reaction with the fibre. Hydrolysis of the dye is slower than the

reaction with the alkaline cotton but it is significant and reduces the efficiency of

the fixation process. After dyeing, any unreacted and hydrolysed dye present in the

cotton must be removed by thorough washing. This ensures that no colour will

bleed from the cotton on subsequent washing during use. The higher the

substantivity of the reactive dye for the cotton, the more difficult it is to wash out

unfixed dye from the material. Many of the first reactive dyes had quite simple

molecular structures and low substantivity for cotton, so that the removal of

hydrolysed dye from the material by washing was relatively easy. This is not

necessarily true for reactive dyes of more complicated molecular structure.