Page 553 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 553

CHAPTER 43: The Pathophysiology and Differential Diagnosis of Acute Respiratory Failure 373

TABLE 43-3 Mechanistic Approach to Respiratory Failure

Type I, Acute Hypoxemic Type II, Ventilatory Type III, Perioperative Type IV, Shock

Mechanism Q ˙ s/Q ˙ t V ˙ a Atelectasis Hypoperfusion

Etiology Airspace flooding 1. CNS drive 1. FRC 1. Cardiogenic

2. N-M coupling 2. CV 2. Hypovolemic

3. Work/dead space 3. Septic

Clinical Description 1. ARDS 1. Overdose/CNS injury 1. Supine/obese, ascites/peritonitis 1. Myocardial infarct, pulmonary hypertension

2. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema 2. Myasthenia gravis, polyradiculitis/ 2. Age/smoking, fluid overload, 2. Hemorrhage, dehydration, tamponade

ALS, botulism/curare bronchospasm, airway secretions

3. Pneumonia 3. Asthma/COPD, pulmonary fibrosis,

kyphoscoliosis

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; FRC, functional residual capacity; N-M,

neuromuscular; Q ˙ s/Q ˙ t, intrapulmonary shunt; V ˙ a, alveolar ventilation.

relation to their perfusion (low V ˙ a/Q ˙ units), and the hypoxemia is made leading to respiratory muscle dysfunction and fatigue. The schematic

worse by low mixed venous oxygen content 30-33 (see Chap. 52); again, illustration of the normal respiratory system (see Fig. 43-3A) indicates

correct this hypoxemia (see Fig. 43-2A). By that spontaneous respiration is effected by the pressure (ΔP) generated

modest increments in Fi O 2

of 1.0 cannot fully correct the hypoxemia induced by inspiratory muscles to expand the lung and chest wall (ΔV) against

contrast, even an Fi O 2

by increased Q ˙ s/Q ˙ t (see Fig. 43-2B), and this refractory hypoxemia of their elastance and to cause inspiratory flow (V ˙ i) past the airways resis-

AHRF is often associated with increased V ˙ e and V ˙ a and so decreased tance (R). When R is increased in acute-on-chronic respiratory failure

34

1 (see Chap. 52). (ACRF) or in status asthmaticus, the P required to breathe often

■ ABNORMALITIES IN RESPIRATORY MECHANICS exceeds the strength of the respiratory muscles, resulting in fatigue of

Pa CO 2

the muscles. When such a patient is mechanically ventilated using a

These two classic types of RF have distinctly different abnormalities in volume-controlled mode, the peak pressure (Ppeak) generated at the

the mechanics of breathing (Fig. 43-3), while they share mechanisms airway opening increases well above the normal value (about 20 cm H 2O

A Very low V /Q B Q /Q Acute hypoxemic

S

T

A

Acute airflow obstruction respiratory failure

140 280 PI O 2 140 700

PI O 2

PA O 2 PA O 2 PA O 2 PA O 2

100 240 27 55 100 660 27 32

2 1

PV O 2 PV O 2 PV O 2 PV O 2

27 40ū 27 40 27 32 27 32

40 100 40 50

Pa O 2 Pa O 2

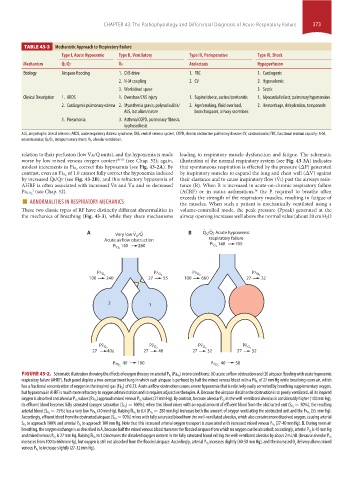

) in two conditions: (A) acute airflow obstruction and (B) airspace flooding with acute hypoxemic

FIGURE 43-2. Schematic illustration showing the effects of oxygen therapy on arterial P O 2 (Pa O 2

-

respiratory failure (AHRF). Each panel depicts a two-compartment lung in which each airspace is perfused by half the mixed venous blood with a Pv O 2 of 27 mm Hg while breathing room air, which

) of 0.21. Acute airflow obstruction causes severe hypoxemia that is relatively easily corrected by breathing supplementary oxygen,

has a fractional concentration of oxygen in the inspired gas (Fi O 2

but hypoxemia in AHRF is much more refractory to oxygen administration and so requires adjunctive therapies. A. Because the airspace distal to the obstruction is so poorly ventilated, all its inspired

in the well-ventilated alveolus is considerably higher (100 mm Hg),

oxygen is absorbed and alveolar P O 2 values (Pa O 2 ) approach mixed venous P O 2 values (27 mm Hg). By contrast, because alveolar P O 2

= 50%), the resulting

its effluent blood becomes fully saturated (oxygen saturation [S O 2 ] = 100%); when this blood mixes with an equal amount of effluent blood from the obstructed unit (S O 2

(55 mm Hg).

arterial blood (S O 2 = 75%) has a very low Pa O 2 (40 mm Hg). Raising Fi O 2 to 0.4 (P O 2 = 280 mm Hg) increases both the amount of oxygen ventilating the obstructed unit and the Pa O 2

= 90%) mixes with fully saturated blood from the well-ventilated alveolus, which also contains more dissolved oxygen, causing arterial

Accordingly, effluent blood from the obstructed airspace (S O 2

(27-40 mm Hg). B. During room air

S O 2 to approach 100% and arterial P O 2 to approach 100 mm Hg. Note that this increased arterial oxygen transport is associated with increased mixed venous P O 2

is 40 mm Hg

breathing, the oxygen exchange is as described in A, because half the mixed venous blood traverses the flooded airspace from which no oxygen can be absorbed; accordingly, arterial P O 2

and mixed venous P O 2 is 27 mm Hg. Raising Fi O 2 to 1.0 increases the dissolved oxygen content in the fully saturated blood exiting the well-ventilated alveolus by about 2 mL/dL (because alveolar P O 2

increases slightly (40-50 mm Hg), and the increased O delivery allows mixed

increases from 100 to 660 mm Hg), but oxygen is still not absorbed from the flooded airspace. Accordingly, arterial P O 2 2

to increase slightly (27-32 mm Hg).

venous P O 2

section04.indd 373 1/23/2015 2:18:42 PM