Page 554 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 554

374 PART 4: Pulmonary Disorders

V l

A B Normal Normal

Lung V = 0.5 L V = 1 L/s V = 1.0 L V = 2 L/s

T

T

resistance (R) Pel = 10: E = 20 Pel = 20: E = 20

60 Pr = 10: R = 10 Pr = 10: R = 10

Lung

elastance (E) 40

Pr = 20

20 Pr = 10

Pel = 20

Pel = 10

Abnormal Abnormal

V V

elastance resistance

V T = 0.5 L V = 1 L/s V T = 0.5 L V = 1 L/s

P AO

Pel = 50: E = 100 Pel = 10: E = 20

Pr = 10: R = 10 Pr = 50: R = 50

60

Respiratory Pr = 10

P ab Pr = 50

muscles ( P) 40

20 Pel = 50

P = V × E + Flow × R Pel = 10

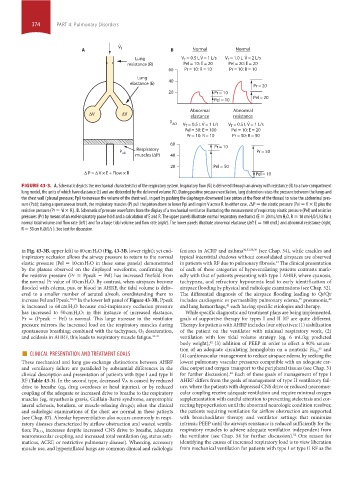

FIGURE 43-3. A. Schematic depicts the mechanical characteristics of the respiratory system. Inspiratory flow (V ˙ i) is delivered through an airway with resistance (R) to a two-compartment

lung model, the units of which have elastance (E) and are distended by the delivered volume (V). During positive pressure ventilation, lung distention raises the pressure between the lungs and

the chest wall (pleural pressure; Ppl) to increase the volume of the chest wall, in part by pushing the diaphragm downward (see piston at the floor of the thorax) to raise the abdominal pres-

sure (Pab); during a spontaneous breath, the respiratory muscles (P) pull the piston down to lower Ppl and inspire V across R. In either case, ΔP = the elastic pressure (Pel = V × E) plus the

resistive pressure (Pr = V ˙ i × R). B. Schematic of pressure waveforms from the display of a mechanical ventilator illustrating the measurement of respiratory elastic pressure (Pel) and resistive

pressures (Pr) by means of an end-inspiratory pause hold and a calculation of E and R. The upper panels illustrate normal respiratory mechanics (E = 20 mL/cm H 2O, R = 10 cm H 2O/L/s) for a

normal tidal volume and flow rate (left ) and for a large tidal volume and flow rate (right). The lower panels illustrate abnormal elastance (left E = 100 cm/L) and abnormal resistance (right,

R = 50 cm H 2O/L/s ). See text for discussion.

in Fig. 43-3B, upper left) to 60 cm H 2O (Fig. 43-3B, lower right); yet end- features in ACRF and asthma 30,31,38,39 (see Chap. 54), while crackles and

inspiratory occlusion allows the airway pressure to return to the normal typical interstitial shadows without consolidated airspaces are observed

elastic pressure (Pel = 10 cm H 2O in these same panels) demonstrated in patients with RF due to pulmonary fibrosis. The clinical presentation

33

by the plateau observed on the displayed waveforms, confirming that of each of these categories of hypoventilating patients contrasts mark-

the resistive pressure (Pr = Ppeak − Pel) has increased fivefold from edly with that of patients presenting with type I AHRF, where cyanosis,

the normal Pr value of 10 cm H 2O. By contrast, when airspaces become tachypnea, and refractory hypoxemia lead to early identification of

flooded with edema, pus, or blood in AHRF, the tidal volume is deliv- airspace flooding by physical and radiologic examinations (see Chap. 52).

ered to a smaller number of aerated alveoli, overdistending them to The differential diagnosis of the airspace flooding leading to Q ˙ s/Q ˙ t

increase Pel and Ppeak. 35,36 In the lower left panel of Figure 43-3B, Ppeak includes cardiogenic or permeability pulmonary edema, pneumonia,

35

40

is increased to 60 cm H 2O because end-inspiratory occlusion pressure and lung hemorrhage, each having specific etiologies and therapy.

41

has increased to 50 cm H 2O; in this instance of increased elastance, While specific diagnostic and treatment plans are being implemented,

Pr = (Ppeak − Pel) is normal. This large increase in the ventilator goals of supportive therapy for types I and II RF are quite different.

pressure mirrors the increased load on the respiratory muscles during Therapy for patients with AHRF includes four objectives: (1) stabilization

spontaneous breathing; combined with the tachypnea, O 2 desaturation, of the patient on the ventilator with minimal respiratory work, (2)

and acidosis in AHRF, this leads to respiratory muscle fatigue. 35-37 ventilation with low tidal volume strategy (eg, 6 mL/kg predicted

body weight), (3) addition of PEEP in order to effect a 90% satura-

42

■ CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND TREATMENT GOALS tion of an adequate circulating hemoglobin on a nontoxic Fi O 2 , and

43

(4) cardiovascular management to reduce airspace edema by seeking the

These mechanical and lung gas-exchange distinctions between AHRF lowest pulmonary vascular pressures compatible with an adequate car-

and ventilatory failure are paralleled by substantial differences in the diac output and oxygen transport to the peripheral tissues (see Chap. 31

44

clinical description and presentation of patients with type I and type II for further discussion). Each of these goals of management of type I

RF (Table 43-3). In the second type, decreased V ˙ a is caused by reduced AHRF differs from the goals of management of type II ventilatory fail-

drive to breathe (eg, drug overdoses or head injuries), or by reduced ure, where the patients with depressed CNS drive or reduced neuromus-

coupling of the adequate or increased drive to breathe to the respiratory cular coupling receive adequate ventilation and require minimal oxygen

muscles (eg, myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, amyotrophic supplementation with careful attention to preventing atelectasis and cor-

lateral sclerosis, botulism, or muscle-relaxing drugs); often the clinical recting hypoperfusion until the abnormal neurologic condition resolves;

and radiologic examinations of the chest are normal in these patients the patients requiring ventilation for airflow obstruction are supported

(see Chap. 87). Alveolar hypoventilation also occurs commonly in respi- with bronchodilator therapy and ventilator settings that minimize

ratory diseases characterized by airflow obstruction and wasted ventila- intrinsic PEEP until the airways resistance is reduced sufficiently for the

increases despite increased CNS drive to breathe, adequate respiratory muscles to achieve adequate ventilation independent from

tion; Pa CO 2

52

neuromuscular coupling, and increased total ventilation (eg, status asth- the ventilator (see Chap. 54 for further discussion). One reason for

maticus, ACRF, or restrictive pulmonary disease). Wheezing, accessory identifying the causes of increased respiratory load is to view liberation

muscle use, and hyperinflated lungs are common clinical and radiologic from mechanical ventilation for patients with type I or type II RF as the

section04.indd 374 1/23/2015 2:18:43 PM