Page 71 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 71

40 PART 1: An Overview of the Approach to and Organization of Critical Care

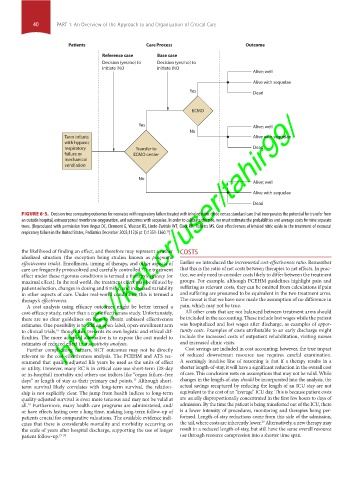

Patients Care Process Outcome

Reference case Base case

Decision (yes/no) to Decision (yes/no) to

initiate iNO initiate iNO

Alive; well

Alive with sequelae

Yes Dead

https://kat.cr/user/tahir99/

ECMO

Yes Alive; well

No

Term infants Alive with sequelae

with hypoxic

respiratory Transfer to Dead

failure or ECMO center

mechanical

ventilation

No

Alive; well

Alive with sequelae

Dead

FIGURE 6-3. Decision tree comparing outcomes for neonates with respiratory failure treated with inhaled nitric oxide versus standard care that incorporates the potential for transfer from

an outside hospital, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and outcomes with sequelae. In order to calibrate the tree, we must estimate the probabilities and average costs for nine separate

trees. (Reproduced with permission from Angus DC, Clermont G, Watson RS, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clark RH, Roberts MS. Cost-effectiveness of inhaled nitric oxide in the treatment of neonatal

15

respiratory failure in the United States, Pediatrics December 2003;112(6 pt 1):1351-1360. )

the likelihood of finding an effect, and therefore may represent a rather COSTS

idealized situation (the exception being studies known as pragmatic

effectiveness trials). Enrollment, timing of therapy, and other aspects of Earlier we introduced the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. Remember

care are frequently protocolized and carefully controlled. The treatment that this is the ratio of net costs between therapies to net effects. In prac-

effect under these rigorous conditions is termed a therapy’s efficacy (or tice, we only need to consider costs likely to differ between the treatment

maximal effect). In the real world, the treatment effect may be diluted by groups. For example, although PCEHM guidelines highlight pain and

patient selection, changes in dosing and timing, and increased variability suffering as relevant costs, they can be omitted from calculations if pain

in other aspects of care. Under real-world conditions, this is termed a and suffering are presumed to be equivalent in the two treatment arms.

therapy’s effectiveness. The caveat is that we have now made the assumption of no difference in

A cost analysis using efficacy outcomes might be better termed a pain, which may not be true.

cost-efficacy study, rather than a cost-effectiveness study. Unfortunately, All other costs that are not balanced between treatment arms should

there are no clear guidelines on how to obtain unbiased effectiveness be included in the accounting. These include lost wages while the patient

estimates. One possibility is to add an open-label, open-enrollment arm was hospitalized and lost wages after discharge, as examples of oppor-

to clinical trials, though this presents its own logistic and ethical dif- tunity costs. Examples of costs attributable to an early discharge might

16

ficulties. The more accepted alternative is to expose the cost model to include the increased costs of outpatient rehabilitation, visiting nurses

estimates of reduced effect in a sensitivity analysis. and increased clinic visits.

Further complicating matters, RCT outcomes may not be directly Cost savings are included in cost accounting; however, the true impact

relevant to the cost-effectiveness analysis. The PCEHM and ATS rec- of reduced downstream resource use requires careful examination.

ommend that quality-adjusted life years be used as the units of effect A seemingly intuitive line of reasoning is that if a therapy results in a

or utility. However, many RCTs in critical care use short-term (28-day shorter length-of-stay, it will have a significant reduction in the overall cost

or in-hospital) mortality and others use indices like “organ failure–free of care. This conclusion rests on assumptions that may not be valid. While

days” or length of stay as their primary end points. Although short- changes in the length-of-stay should be incorporated into the analysis, the

17

term survival likely correlates with long-term survival, the relation- actual savings recaptured by reducing the length of an ICU stay are not

ship is not explicitly clear. The jump from health indices to long-term equivalent to the cost of an “average” ICU day. This is because patient costs

quality-adjusted survival is even more tenuous and may not be valid at are usually disproportionally concentrated in the first few hours to days of

all. Furthermore, many health care programs are administered, and/ admission. By the time the patient is being transferred out of the ICU, there

18

or have effects lasting over a long time, making long-term follow-up of is a lower intensity of procedures, monitoring and therapies being per-

patients crucial for comparative valuations. The available evidence indi- formed. Length-of-stay reductions come from this side of the admission,

29

cates that there is considerable mortality and morbidity occurring on the tail, where costs are inherently lower. Alternatively, a new therapy may

the scale of years after hospital discharge, supporting the use of longer result in a reduced length-of-stay, but still have the same overall resource

patient follow-up. 19-28 use through resource compression into a shorter time span.

Section01.indd 40 1/22/2015 9:36:54 AM