Page 112 - Cardiac Nursing

P. 112

8:4

9/0

009

1 A

ra

96.

p06

9-0

9/2

pta

8 A

qxd

0

P

M

e 8

g

K34

0-c

03_

LWB K34 0-c 03_ p06 9-0 96. qxd 0 9/0 9/2 009 0 0 8:4 1 A M P a a g e 8 8 A pta ra

LWBK340-c03_p069-096.qxd 09/09/2009 08:41 AM Page 88 Aptara

L L LWB

88 PA R T I / Anatomy and Physiology

increases baroreflex-mediated sympathetic activity, is manifested Tilt up Tilt down

as a compensatory increase in heart rate and peripheral resistance.

On release of the strain (phase 3), there is an abrupt decrease in 85 85

arterial pressure (release of aortic compression) and a rapid rise in

venous return (decreased caval compression with restoration of MAP (mmHg) 80 80

the inferior vena cava to right atrial pressure gradient) without a 75 75

change in heart rate. Finally, during phase 4 (overshoot), when the

increased venous return reaches the left ventricle, there is a

progressive increase in left ventricular stroke volume, blood pres- 110

sure, and pulse pressure above baseline caused by an increase in SV (ml) 110 100

100

cardiac output, secondary to the increased venous return into the

vasoconstricted systemic vasculature. The overshoot of blood pres- 90 90

sure, pulse pressure, and cardiac output stimulates vagal activity,

leading to reflex bradycardia. 255,256

In the clinical setting, the effects of the Valsalva maneuver may 72 72

be observed when a patient strains during defecation or vomit- 70 70

ing. 257 It is the reflex bradycardia and the sequelae of the Valsalva HR (beats•min) 68 68

maneuver (cardiac arrhythmias, sudden cardiac arrest, cerebral and

subarachnoid hemorrhage, rupture of a dissecting aortic aneurysm) 66 66

that are observed clinically. 258 Patients who may be at increased risk

for an adverse response to the Valsalva maneuver include those with

cardiac disease (e.g., heart failure) and older individuals. 254,259 In- 6.2 6.2

terventions to protect this high-risk group from the sequelae of the 5.8 5.8

Valsalva maneuver (e.g., positioning, and avoiding straining during CO (l•min) 5.4 5.4

a bowel movement or vomiting) should be performed. 5.0 5.0

4.6 4.6

OVERALL CONTROL 100 100

Baroreflex Control of Blood Pressure TPC (ml•mmHg•min) 90 90

80

80

The arterial baroreflex is the primary mechanism of control for 70 70

the short-term or rapid control of arterial blood pressure. 260–263

20 30 40 50 60 20 30 40 50 60

Neurohumoral factors (predominantly the control of sodium ex-

cretion) are primarily responsible for long-term or slower blood Time (s) Time (s)

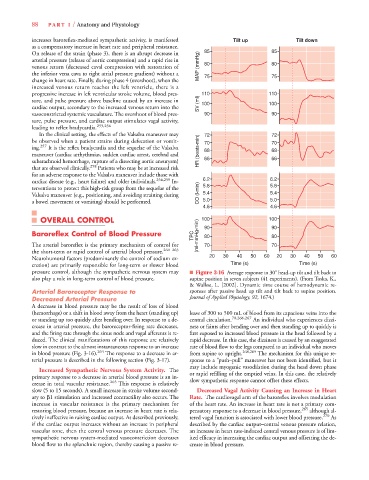

pressure control, although the sympathetic nervous system may ■ Figure 3-16 Average response to 30 head-up tilt and tilt back to

also play a role in long-term control of blood pressure. supine position in seven subjects (41 experiments). (From Toska, K.,

& Walløe, L. [2002]. Dynamic time course of hemodynamic re-

Arterial Baroreceptor Response to sponses after passive head up tilt and tilt back to supine position.

Decreased Arterial Pressure Journal of Applied Physiology, 92, 1674.)

A decrease in blood pressure may be the result of loss of blood

(hemorrhage) or a shift in blood away from the heart (standing up) lease of 300 to 500 mL of blood from its capacious veins into the

or standing up too quickly after bending over. In response to a de- central circulation. 70,266,267 An individual who experiences dizzi-

crease in arterial pressure, the baroreceptor-firing rate decreases, ness or faints after bending over and then standing up to quickly is

and the firing rate through the sinus node and vagal afferents is re- first exposed to increased blood pressure in the head followed by a

duced. The clinical manifestations of this response are relatively rapid decrease. In this case, the dizziness is caused by an exaggerated

slow in contrast to the almost instantaneous response to an increase rate of blood flow to the legs compared to an individual who moves

in blood pressure (Fig. 3-16). 264 The response to a decrease in ar- from supine to upright. 268,269 The mechanism for this unique re-

terial pressure is described in the following section (Fig. 3-17). sponse to a “push–pull” maneuver has not been identified, but it

may include myogenic vasodilation during the head down phase

Increased Sympathetic Nervous System Activity. The or rapid refilling of the emptied veins. In this case, the relatively

primary response to a decrease in arterial blood pressure is an in- slow sympathetic response cannot offset these effects.

crease in total vascular resistance. 265 This response is relatively

slow (5 to 15 seconds). A small increase in stroke volume second- Decreased Vagal Activity Causing an Increase in Heart

ary to 1 stimulation and increased contractility also occurs. The Rate. The cardiovagal arm of the baroreflex involves modulation

increase in vascular resistance is the primary mechanism for of the heart rate. An increase in heart rate is not a primary com-

restoring blood pressure, because an increase in heart rate is rela- pensatory response to a decrease in blood pressure, 265 although al-

tively ineffective in raising cardiac output. As described previously, tered vagal function is associated with lower blood pressure. 270 As

if the cardiac output increases without an increase in peripheral described by the cardiac output–central venous pressure relation,

vascular tone, then the central venous pressure decreases. The an increase in heart rate-induced central venous pressure is of lim-

sympathetic nervous system-mediated vasoconstriction decreases ited efficacy in increasing the cardiac output and offsetting the de-

blood flow to the splanchnic region, thereby causing a passive re- crease in blood pressure.