Page 696 - Hematology_ Basic Principles and Practice ( PDFDrive )

P. 696

588 Part V Red Blood Cells

Hb F:

O 2 Deoxygenation Hydroxyurea, decitabine?,

HDAC inhibitor?

Avoid Hb polymerization

dehydration Hb S concentration Replace Hb S with Hb A:

Exchange transfusion,

Acidosis Stem cell transplant

RBC rigidity RBC adhesion Hemolysis

Endothelial damage Anemia Nitric oxide

Erythropoietin? Antioxidants?

Iron chelation?

Coagulation Inflammatory

pathway activation pathway activation

Aspirin?

Vasoocclusion

Splenic, cerebral, pulmonary, renal, Renal, cardiac, Pulmonary

muscle, bone, retinal, skin complications skin complications hypertension

Vaccination, penicillin, vitamin supplementation,

analgesia, wound care, laser for retinopathy

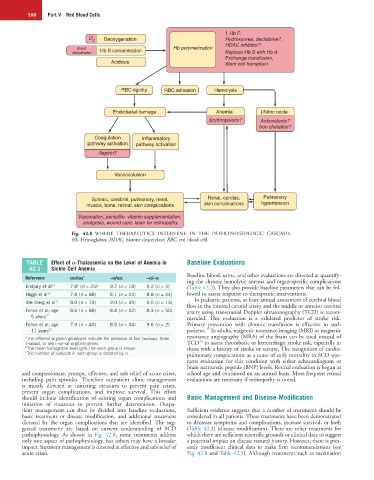

Fig. 42.8 WHERE THERAPEUTICS INTERVENE IN THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC CASCADE.

Hb, Hemoglobin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; RBC, red blood cell.

TABLE Effect of α-Thalassemia on the Level of Anemia in Baseline Evaluations

42.1 Sickle Cell Anemia

Reference αα/αα a −α/αα −α/−α Baseline blood, urine, and other evaluations are directed at quantify-

ing the chronic hemolytic anemia and organ-specific complications

Embury et al 29 7.8 (n = 25) c 9.7 (n = 18) 9.2 (n = 4) (Table 42.2). They also provide baseline parameters that can be fol-

b

Higgs et al 30 7.8 (n = 88) 8.1 (n = 44) 8.8 (n = 44) lowed to assess response to therapeutic interventions.

In pediatric patients, at least annual assessment of cerebral blood

Steinberg et al 31 8.0 (n = 73) 9.0 (n = 39) 9.5 (n = 13)

flow in the internal carotid artery and the middle or anterior cerebral

Felice et al; age 8.6 (n = 88) 8.4 (n = 52) 8.3 (n = 50) artery using transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (TCD) is recom-

5 years 32 mended. This evaluation is a validated predictor of stroke risk.

Felice et al; age 7.9 (n = 40) 8.5 (n = 34) 9.6 (n = 2) Primary prevention with chronic transfusion is effective in such

33

11 years 32 patients. In adults, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic

a The different α-globin genotypes indicate the presence of four (αα/αα), three resonance angiography (MRA) of the brain can be used instead of

34

(−α/αα), or two (−α/−α) α-globin genes. TCD to assess thrombotic or hemorrhagic stroke risk, especially in

b The mean hemoglobin level (g/dL) for each group is shown. those with a history of stroke or seizure. The recognition of cardio-

c The number of subjects in each group is denoted by n. pulmonary complications as a cause of early mortality in SCD war-

rants evaluation for this condition with either echocardiogram or

brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels. Retinal evaluation is begun at

and compassionate, prompt, effective, and safe relief of acute crises, school age and continued on an annual basis. More frequent retinal

including pain episodes. Therefore outpatient clinic management evaluations are necessary if retinopathy is noted.

is mostly directed at initiating measures to prevent pain crises,

prevent organ complications, and improve survival. This effort

should include identification of existing organ complications and Basic Management and Disease Modification

initiation of measures to prevent further deterioration. Outpa-

tient management can thus be divided into baseline evaluations, Sufficient evidence suggests that a number of treatments should be

basic treatment or disease modification, and additional treatment considered in all patients. These treatments have been demonstrated

dictated by the organ complications that are identified. The sug- to decrease symptoms and complications, increase survival, or both

gested treatments are based on current understanding of SCD (Table 42.3) (disease modification). There are other treatments for

pathophysiology. As shown in Fig. 42.8, some treatments address which there are sufficient scientific grounds or clinical data to suggest

only one aspect of pathophysiology, but others may have a broader a potential impact on disease natural history. However, there is pres-

impact. Inpatient management is directed at effective and safe relief of ently insufficient clinical data to make firm recommendations (see

acute crises. Fig. 42.8 and Table 42.3). Although treatments such as vaccination