Page 1531 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 1531

1050 PART 10: The Surgical Patient

to airway closure at higher lung volumes. As a group, smokers tend to Patients undergoing upper abdominal operations have a significant

41

have higher closing volumes, so that the combination of age and smoking decrease in the maximal transdiaphragmatic pressure at FRC, which is not

increases the likelihood of significant postoperative hypoxemia. It has altered by use of epidural analgesia. This finding suggests that the respira-

50

generally been accepted that chronic cigarette smoking increases the tory dysfunction after upper abdominal surgery may result from a primary

incidence of postoperative respiratory complications, which may result effect of the procedure on diaphragmatic function. Ford and coworkers

not only from an alteration in the respiratory defense mechanisms, but showed that there is a switch from predominantly abdominal breathing to

also an increase in airway resistance and the work of breathing. It has rib cage breathing in the postoperative period in patients undergoing upper

been demonstrated that cessation of smoking for over 8 weeks is an abdominal surgery (Fig. 110-3). Diaphragmatic dysfunction was simi-

51

effective means of decreasing postoperative respiratory complications. larly identified in an animal model undergoing cholecystectomy. These

52

42

Although it has been suggested that abstinence too soon prior to surgery studies suggest that general anesthesia may not be responsible for the post-

may increase the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications, aggres- operative diaphragmatic dysfunction. Mere traction on the gallbladder in

sive counseling for smoking cessation prior to any elective surgical an animal model also produced similar effects on diaphragmatic function. 53

procedure still appears to be the best approach. 43 Although open cholecystectomy has been associated with significant

Because small airways in the periphery of the lung are not supported depression in postoperative pulmonary function; several reports 54-56

by cartilage, they tend to be influenced significantly by changes in pleu- have demonstrated less impairment of postoperative pulmonary func-

ral pressures. The maintenance of a positive transpulmonary pressure tion following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There still is a decrease

resulting from the negative intrapleural pressure maintains patency in FRC immediately after the operation, but it is much smaller and of

of the small airways. Breathing at a reduced FRC, such as occurs with significantly shorter duration than with the open procedure, and the

abdominal pain, tends to lead to positive pleural pressures in the depen- VC and FRC return to essentially preoperative levels within 24 hours.

56

dent areas of the lung, and therefore creates a predisposition to alveolar Therefore from the respiratory standpoint, laparoscopic cholecystec-

collapse. Complete collapse results in continued perfusion of nonven- tomy is superior to open cholecystectomy and should be the preferred

tilated areas, or shunting; when the airways are merely narrowed, the method for critically ill patients requiring this procedure. The increase

ventilation:perfusion ratio may be low, which also impairs gas exchange in intra-abdominal pressure with pneumoperitoneum associated with

and leads to hypoxemia. the laparoscopic procedure has a minimal hemodynamic effect, but in

The patient with multiple fractures is at increased risk for developing patients with decreased cardiopulmonary reserve this may prove signifi-

pulmonary complications, not only from thromboembolic complications, cant, warranting close hemodynamic monitoring in the operating room

including fat embolism, but also from atelectasis and pneumonia. A

major predisposing factor in these patients is the prolonged period of

imposed bed rest, particularly in the supine position, with its resultant Abdomen

effect on lung mechanics and lung volumes. Early operative stabilization 14

of fractures in these patients has been shown to decrease pulmonary RIB cage

morbidity because it allows more effective respiratory physiotherapy

44

and early ambulation, as well as frequent changes in body position to

minimize dependent alveolar volume loss. 12

A major cause of morbidity in traumatic quadriplegic patients is

respiratory failure secondary to loss of use of the intercostal muscles of

respiration. It has been suggested that the best position for respiratory

45

therapy in these patients is from horizontal to 35° head-up, whereas the 10

46

maximum FRC is achieved in the 60° to 90° head-up position.

Upper Abdominal Surgery and Diaphragm Dysfunction: Although many

of the factors discussed above are present in patients undergoing most

surgical procedures, the most serious sequelae are found in patients 8

undergoing upper abdominal procedures. In these patients, there is a

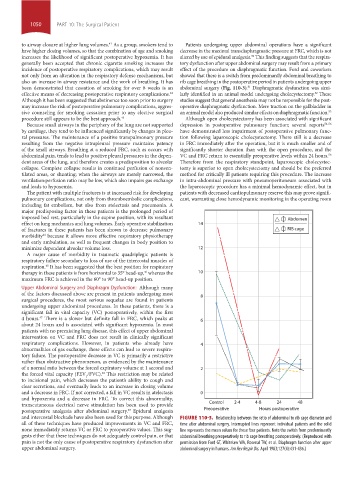

significant fall in vital capacity (VC) postoperatively, within the first

4 hours. There is a slower but definite fall in FRC, which peaks at 6

47

about 24 hours and is associated with significant hypoxemia. In most

patients with no preexisting lung disease, this effect of upper abdominal

intervention on VC and FRC does not result in clinically significant

respiratory complications. However, in patients who already have 4

abnormalities of gas exchange, these effects can lead to severe respira-

tory failure. The postoperative decrease in VC is primarily a restrictive

rather than obstructive phenomenon, as evidenced by the maintenance

of a normal ratio between the forced expiratory volume at 1 second and 2

the forced vital capacity (FEV /FVC). This restriction may be related

48

1

to incisional pain, which decreases the patient’s ability to cough and

clear secretions, and eventually leads to an increase in closing volume

and a decrease in FRC. If not corrected, a fall in VC results in atelectasis 0

and hypoxemia and a decrease in FRC. To correct this abnormality,

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has been used to provide Control 2-4 4-8 24 48

postoperative analgesia after abdominal surgery. Epidural analgesia Preoperative Hours postoperative

49

and intercostal blockade have also been used for this purpose. Although FIGURE 110-3. Relationship between the ratio of abdominal to rib cage diameter and

all of these techniques have produced improvements in VC and FRC, time after abdominal surgery. Interrupted lines represent individual patients and the solid

none immediately returns VC or FRC to preoperative values. This sug- line represents the mean values for these four patients. Note the switch from predominantly

gests either that these techniques do not adequately control pain, or that abdominal breathing preoperatively to rib cage breathing postoperatively. (Reproduced with

pain is not the only cause of postoperative respiratory dysfunction after permission from Ford GT, Whitelaw WA, Rosenal TW, et al. Diaphragm function after upper

upper abdominal surgery. abdominal surgery in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis. April 1983;127(4):431-436.)

section10.indd 1050 1/20/2015 9:19:30 AM