Page 637 - 9780077418427.pdf

P. 637

/Volume/201/MHDQ233/tat78194_disk1of1/0073378194/tat78194_pagefiles

tiL12214_ch24_597-622.indd Page 614 9/23/10 11:09 AM user-f465

tiL12214_ch24_597-622.indd Page 614 9/23/10 11:09 AM user-f465 /Volume/201/MHDQ233/tat78194_disk1of1/0073378194/tat78194_pagefile

ter, so it sinks and displaces water of less salinity. Likewise, sea-

water with a larger amount of suspended sediments has a higher

relative density than clear water, so it sinks and displaces clear

water. The following describes how these three ways of chang-

ing the density of seawater result in the ocean current known as

a density current, which is an ocean current that flows because

of density differences.

Earth receives more incoming solar radiation in the trop-

ics than it does at the poles, which establishes a temperature

difference between the tropical and polar oceans. The surface

water in the polar ocean is often at or below the freezing point

of freshwater, while the surface water in the tropical ocean av-

erages about 26°C (about 79°F). Seawater freezes at a tempera-

ture below that of freshwater because the salt content lowers

the freezing point. Seawater does not have a set freezing point,

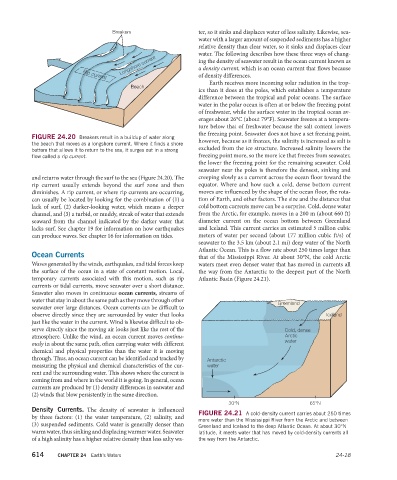

FIGURE 24.20 Breakers result in a buildup of water along

the beach that moves as a longshore current. Where it finds a shore however, because as it freezes, the salinity is increased as salt is

excluded from the ice structure. Increased salinity lowers the

bottom that allows it to return to the sea, it surges out in a strong

flow called a rip current. freezing point more, so the more ice that freezes from seawater,

the lower the freezing point for the remaining seawater. Cold

seawater near the poles is therefore the densest, sinking and

and returns water through the surf to the sea (Figure 24.20). The creeping slowly as a current across the ocean floor toward the

rip current usually extends beyond the surf zone and then equator. Where and how such a cold, dense bottom current

diminishes. A rip current, or where rip currents are occurring, moves are influenced by the shape of the ocean floor, the rota-

can usually be located by looking for the combination of (1) a tion of Earth, and other factors. The size and the distance that

lack of surf, (2) darker-looking water, which means a deeper cold bottom currents move can be a surprise. Cold, dense water

channel, and (3) a turbid, or muddy, streak of water that extends from the Arctic, for example, moves in a 200 m (about 660 ft)

seaward from the channel indicated by the darker water that diameter current on the ocean bottom between Greenland

lacks surf. See chapter 19 for information on how earthquakes and Iceland. This current carries an estimated 5 million cubic

can produce waves. See chapter 16 for information on tides. meters of water per second (about 177 million cubic ft/s) of

seawater to the 3.5 km (about 2.1 mi) deep water of the North

Atlantic Ocean. This is a flow rate about 250 times larger than

Ocean Currents that of the Mississippi River. At about 30°N, the cold Arctic

Waves generated by the winds, earthquakes, and tidal forces keep waters meet even denser water that has moved in currents all

the surface of the ocean in a state of constant motion. Local, the way from the Antarctic to the deepest part of the North

temporary currents associated with this motion, such as rip Atlantic Basin (Figure 24.21).

currents or tidal currents, move seawater over a short distance.

Seawater also moves in continuous ocean currents, streams of

water that stay in about the same path as they move through other

seawater over large distances. Ocean currents can be difficult to

observe directly since they are surrounded by water that looks

just like the water in the current. Wind is likewise difficult to ob-

serve directly since the moving air looks just like the rest of the

at mosphere. Unlike the wind, an ocean current moves continu-

ously in about the same path, often carrying water with different

chemical and physical properties than the water it is moving

through. Thus, an ocean current can be identified and tracked by

measuring the physical and chemical characteristics of the cur-

rent and the surrounding water. This shows where the current is

coming from and where in the world it is going. In general, ocean

currents are produced by (1) density differences in seawater and

(2) winds that blow persistently in the same direction.

Density Currents. The density of seawater is influenced

FIGURE 24.21 A cold-density current carries about 250 times

by three factors: (1) the water temperature, (2) salinity, and

more water than the Mississippi River from the Arctic and between

(3) sus pended sediments. Cold water is generally denser than Greenland and Iceland to the deep Atlantic Ocean. At about 30°N

warm water, thus sinking and displacing warmer water. Sea water latitude, it meets water that has moved by cold-density currents all

of a high salinity has a higher relative density than less salty wa- the way from the Antarctic.

614 CHAPTER 24 Earth’s Waters 24-18