Page 439 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 439

CHAPTER 38: Acute Right Heart Syndromes 309

exaggerated “hang out” period (ventricular outflow between the onset

combination of acute pulmonary hypertension with profound RV of right ventricular pressure decline and pulmonary valve closure) opti-

systolic and diastolic dysfunction) results in spiraling end-organ mizes pump efficiency and results in a triangular pressure-volume rela-

dysfunction. tionship compared with the square wave pump of the LV. Consequently

• Clues to recognizing RHS as a cause of shock include a history of a RV wall stress is low under normal physiological conditions and RV

condition that is associated with pulmonary hypertension, elevated coronary perfusion occurs in both diastole and systole, unlike the LV. 2

neck veins, peripheral edema greater than pulmonary edema, or a The functional differences between RV and LV result from ontogenic,

right-sided third heart sound, in addition to electrocardiographic, structural, cellular, and biochemical differences. The RV has a higher

radiographic, and echocardiographic findings. proportion of rapidly contractile α-myosin heavy chain filaments than

3

• Plasma biomarkers are nonspecific but echocardiography is the LV. Additionally, while both LV and RV are equally inotropically

responsive to selective β -adrenergic receptor (AR) agonism, RV and LV

extremely valuable, not only for demonstrating the presence of myocytes respond differentially to α -adrenergic receptor stimulation.

1

4

RHS, but also for guiding hemodynamic management. Selective α -AR stimulation is negatively inotropic in RV trabeculae but

1

1

• Progressive right heart shock can be worsened by excessive fluid infu- positively inotropic in LV trabeculae.

sion, concomitant left ventricular failure, inappropriate application of

extrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and hypoxia. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF RIGHT HEART SYNDROMES

• The drug of choice for resuscitation to reduce systemic oxygen demand

while improving oxygen delivery is dobutamine, initially infused at Acute and acute-on-chronic right heart syndromes develop as a con-

5 µg/kg per minute. Systemically active vasoconstrictors may pro- sequence of a combination of factors that that include impaired RV

vide additional benefit. contractility, RV pressure overload or volume overload (Fig. 38-1). 5

Under conditions of increased RV impedance (eg, pulmonary ste-

• Inhaled nitric oxide or prostacyclin and oral PDE-inhibitors (eg, silde- nosis or pulmonary embolism) the RV pressure-volume relationship

nafil) or extracorporeal mechanical assist devices may be beneficial assumes a square wave appearance similar to that of the LV. Acute

6

in improving pulmonary hemodynamics and oxygenation, but may RV pressure overload leads to enhanced contractility through two

not improve survival. mechanisms: (1) the Anrep effect (homeometric autoregulation)—an

adrenergically—independent contractile enhancement and (2) the

Frank-Starling mechanism. In contrast, acute volume overload evokes

predominantly Starling-mediated contractile enhancement. Unlike

In the majority of patients with shock due to “pump failure,” assessment the LV, however, even modest acute increases in RV afterload may

is focused appropriately on the left ventricle. However, in a substantial precipitate ventricular failure. Right ventricular ejection fraction falls

minority of patients, right heart dysfunction is the cause of shock. as Pa resistance/pressure rises and RV end-systolic and end-diastolic

Examples include acute pulmonary embolism (PE), other causes of pressures rise. During acute Pa hypertension, RV preload, after-load,

acute right heart pressure overload (eg, acute respiratory distress and contractile state rise at the same time that heart rate rises. These

syndrome [ARDS] treated with positive pressure ventilation), acute features join to raise the RV myocardial oxygen consumption. At the

deterioration in patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension, and same time, when an acute RHS is sufficiently severe to cause systemic

right ventricular infarction. Although right ventricular infarction dif- hypotension, coronary perfusion of the RV may fall. The combination

fers from the other right heart syndromes (RHS) in that the pulmonary

artery pressure is not high, in many other regards right ventricular

infarction resembles the other syndromes, so we will consider them Right heart

together. Failure to consider the right heart in the differential diagnosis

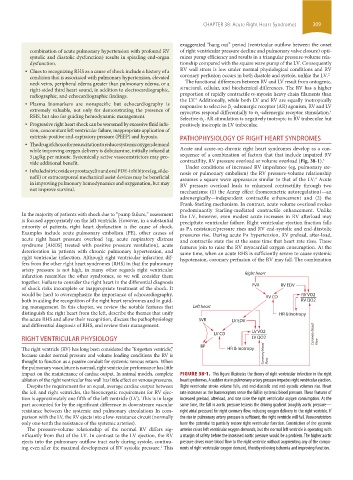

of shock risks incomplete or inappropriate treatment of the shock. It PVR RV EDV

would be hard to overemphasize the importance of echocardiography, RV CO RV VO2

both in aiding the recognition of the right heart syndromes and in guid- RV QO2

ing management. In this chapter, we review the notable features that Left heart

distinguish the right heart from the left, describe the themes that unify HR & Inotropy

the acute RHS and allow their recognition, discuss the pathophysiology SVR LV EDV

and differential diagnosis of RHS, and review their management.

LV VO2

LV CO Coronary blood

RIGHT VENTRICULAR PHYSIOLOGY LV QO2

BP Flow

The right ventricle (RV) has long been considered the “forgotten ventricle,” HR & Inotropy

because under normal pressure and volume loading conditions the RV is Coronary blood

thought to function as a passive conduit for systemic venous return. When Flow

the pulmonary vasculature is normal, right ventricular performance has little

impact on the maintenance of cardiac output. In animal models, complete FIGURE 38-1. This figure illustrates the theory of right ventricular infarction in the right

ablation of the right ventricular free wall has little effect on venous pressures. heart syndromes. A sudden rise in pulmonary artery pressure impedes right ventricular ejection.

Despite the requirement for an equal, average cardiac output between Right ventricular stroke volume falls, and end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes rise. Heart

the left and right ventricles, the bioenergetic requirement for RV ejec- rate increases as the baroreceptors sense the fall in systemic blood pressure. These features of

tion is approximately one fifth of the left ventricle (LV). This is in large increased preload, afterload, and rate raise the right ventricular oxygen consumption. At the

part accounted for by the significant difference in downstream vascular same time, the fall in aortic pressure lessens the driving gradient (roughly aortic pressure—

resistance between the systemic and pulmonary circulations In com- right atrial pressure) for right coronary flow, reducing oxygen delivery to the right ventricle. If

parison with the LV, the RV ejects into a low-resistance circuit (normally the rise in pulmonary artery pressure is sufficient, the right ventricle will fail. Vasoconstrictors

only one-tenth the resistance of the systemic arteries). have the potential to partially restore right ventricular function. Constriction of the systemic

The pressure-volume relationship of the normal RV differs sig- arteries raises left ventricular oxygen demands, but the normal left ventricle is operating with

nificantly from that of the LV. In contrast to the LV ejection, the RV a margin of safety before the increased aortic pressure would be a problem. The higher aortic

ejects into the pulmonary outflow tract early during systole, continu- pressure drives more blood flow to the right ventricle without augmenting any of the compo-

ing even after the maximal development of RV systolic pressure. This nents of right ventricular oxygen demand, thereby relieving ischemia and improving function.

1

section03.indd 309 1/23/2015 2:07:25 PM