Page 449 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 449

CHAPTER 39: Pulmonary Embolic Disorders: Thrombus, Air, and Fat 319

In spite of great strides in the understanding of VTE, pulmonary This creation of dead space has several effects on P CO 2 and end-tidal

embolism (PE) continues to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. CO (ET ), which can provide clues to diagnosis. If minute ventila-

2

CO 2

Critically ill patients form a unique and challenging subset of those at tion (VE) does not change, as occurs in a mechanically ventilated,

risk. The presence of indwelling lines and forced immobility make these muscle-relaxed patient, P CO 2 will rise. However, most patients augment

patients particularly susceptible to venous thromboemboli. Diagnosis, VE more than necessary to maintain elimination of CO , so that P CO 2

2

which is difficult even in ambulatory patients, is further impeded by typically falls with PE. In health, the ET is nearly identical to arterial

CO 2

barriers to communication and physical examination. Moreover, alter- CO . After pulmonary embolization, since end-tidal gas is a mixture of

2

nate explanations for hypoxemia, lung infiltrates, respiratory failure, ventilated alveolar gas (in which Pa CO 2 approximates arterial, or Pa CO 2 )

and hemodynamic instability are readily available, such that a diagnosis as well as the newly created physiologic dead space gas (in which Pa CO 2

of pulmonary thromboembolism may not be considered likely. Finally, approximates inspired P CO 2 , or nearly zero), ET falls in proportion to

CO 2

critically ill patients are likely to have limited cardiopulmonary reserve, the degree of dead space and no longer approximates Pa CO 2 (Fig. 39-1).

https://kat.cr/user/tahir99/

so that pulmonary emboli may be particularly lethal. This principle of a fixed alveolar to arterial gradient for P CO 2 has been

■ PATHOPHYSIOLOGY used to distinguish acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmo-

nary disease (COPD) from pulmonary embolism in patients with acute

15

Venous thrombosis begins with the formation of microthrombi at a site of ventilatory failure. While not yet studied in the critically ill population,

the steady-state end-tidal alveolar dead space fraction—which can be

venous stasis or injury. Thrombosis impedes flow and generates further —has a

vascular injury, favoring progressive clot formation. In some patients, easily derived once one has both an accurate Pa CO 2 and P ET CO 2

sensitivity of 79.5% and a negative predictive value of 90.7% in hospital-

clot becomes substantial and propagates to a proximal vein where it has ized patients with PE. Similar studies report the utility of alveolar dead

16

the potential to embolize to the pulmonary circulation. Thrombus in the space fraction (VADS/VT) when used in conjunction with D-dimer for

vasculature causes chiefly a mechanical obstruction to flow, but also trig- evaluating emergency department patients suspected of having PE.

17

gers the release of vasoactive and, for PE, bronchoreactive substances like However, shortcomings to the VADS/VT approach include the technical

serotonin which can exacerbate ventilation—perfusion mismatch. via

Most clinically relevant pulmonary emboli originate as proximal challenge of simultaneously obtaining a steady-state exhaled gas P CO 2

from an arterial gas sample.

venous thrombi in the leg or pelvic veins. However, in the ICU, the rou- volumetric capnography and P CO 2

In 2010, a more simplified application of the same principle was

tine placement of upper body catheters for vascular access, monitoring, tested by evaluating the combination of exhaled end-tidal CO /O and

drug administration, and nutrition raises the likelihood of important D-dimer in emergency department, hospital ward, or ICU patients sus-

2

2

upper body sources of thrombi. Up to one-third of patients with indwell- pected of PE undergoing multidetector-row CTPA. As alveolar dead

18

ing venous catheters have ultrasound-detectable clot at screening, space fraction rises, the ratio of CO /O falls. A CO /O ratio <0.28

although in one study none were symptomatic, and none developed a was considered positive for increased dead space. Among moderate-

2

2

2

2

18

symptomatic pulmonary embolus over 18 months. Subsequently, in /O <0.28

11

a large international registry of patients with clinically diagnosed VTE, risk patients with a positive D-dimer, the presence of ET CO 2 2

significantly increased the posterior probability of segmental or larger

the proportion of upper extremity DVT was low (4%) and patients with PE, and no segmental or larger clots were observed in patients with

upper extremity DVT were less likely to have PE at presentation (9% CO /O >0.45. The alveolar dead space fraction estimated by this

18

compared to 29% for lower extremity DVT). However, during 90-day method is not sensitive to detecting PE at or below the subsegmental

2

2

12

follow-up, patients with upper extremity DVT developed new PE at the level, and the majority of measurements fall in an intermediate, and

same rate as those with lower extremity, and additional studies report thus potentially clinically unhelpful, range. Furthermore, patients with

12

substantial risks of PE (25%), clot recurrence (8%), or death (24%) hemodynamic instability or those already dosed with thrombolytic

following upper extremity DVT. 13,14 The potential for upper extremity therapy were excluded in this study, and this study was not designed to

thrombi in the ICU has obvious implications for diagnostic strategies, test the safety of withholding further testing or anticoagulation based

which have traditionally focused on detecting lower extremity thrombi, on D-dimer and CO /O results. While we cannot advocate routine use

as well as for therapeutic strategy with respect to vena caval interruption. /O in evaluating patients suspected of PE, an unexplained high

2

2

PE occurs when thrombi detach and are carried through the great of ET CO 2 2

dead space fraction in an ICU patient should prompt consideration of PE.

veins to the pulmonary circulation. Pulmonary vascular occlusion has is present

A widened alveolar to arterial gradient for oxygen (A-a)P O 2

important physiologic consequences that lead to the manifestations of in the majority of patients with PE. However, since in PE hyperventila-

19

illness as well as to clues to diagnosis. The most profound effects of PE may not be low. In unselected patients with PE, only

are evident on gas exchange and the circulation. tion is the rule, Pa O 2 <70 on ABG testing. 19,20 Therefore, a

50% to 60% demonstrate a Pa O 2

Gas Exchange: Physical obstruction to pulmonary artery (Pa) flow normal Pa O 2 does not conclusively exclude a diagnosis of PE. There have

creates dead space in the segments served by the affected arteries. been several efforts to use various combinations of the Pa O 2 , the P CO 2 ,

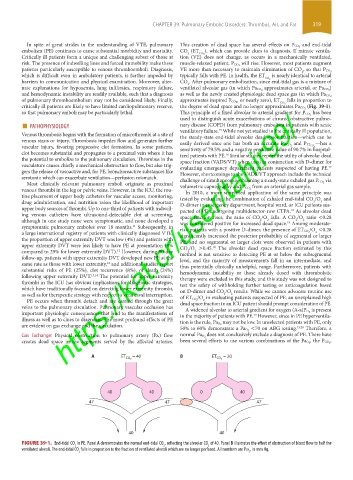

A ET = 40 B ET = 20

CO 2 CO 2

40 40 0 40

47 47 47

40 40

FIGURE 39-1. End-tidal CO in PE. Panel A demonstrates the normal end-tidal CO , reflecting the alveolar CO of 40. Panel B illustrates the effect of obstruction of blood flow to half the

2

2

2

ventilated alveoli. The end-tidal CO falls in proportion to the fraction of ventilated alveoli which are no longer perfused. All numbers are Pco , in mm Hg.

2 2

section03.indd 319 1/23/2015 2:07:30 PM