Page 451 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 451

CHAPTER 39: Pulmonary Embolic Disorders: Thrombus, Air, and Fat 321

30 TABLE 39-1 Symptoms and Signs of Pulmonary Embolism 19,28

Symptom Incidence (%) Sign Incidence (%)

25 distention Dyspnea 80 Tachypnea 90

Left ventricular diastolic pressure 15 Apprehension 60 Tachycardia 2 50 8

Acute RV

Fever

70

Pleuritic pain

50

20

50

Cough

Increased 2nd heart sound (P )

50

Signs of DVT

35

33

Symptoms of DVT

Hemoptysis

25

Shock

10

https://kat.cr/user/tahir99/

Palpitations

10

5

Normal Central chest pain 10 5

Syncope

0

60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140

Left ventricular volume

to a diagnosis of PE. Rare patients with PE have disseminated intravas-

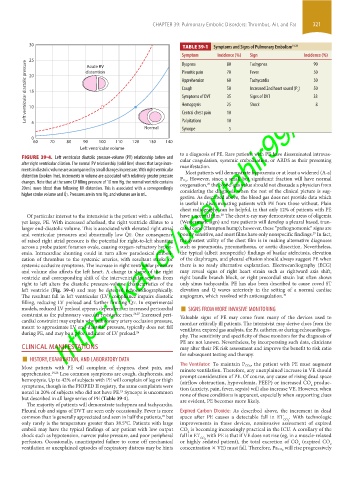

FIGURE 39-4. Left ventricular diastolic pressure-volume (PV) relationship before and cular coagulation, systemic embolization, or ARDS as their presenting

after right ventricular dilation. The normal PV relationship (solid line) shows that large incre- manifestation.

ments in diastolic volume are accompanied by small changes in pressure. With right ventricular Most patients will demonstrate hypoxemia or at least a widened (A-a)

distention (broken line), increments in volume are associated with relatively greater pressure . However, since a small but significant fraction will have normal

changes. Note that at the same LV filling pressure of 10 mm Hg, the normal ventricle contains P O 2 20

oxygenation, the blood-gas value should not dissuade a physician from

20 mL more blood than following RV distention. This is associated with a correspondingly considering the diagnosis when the rest of the clinical picture is sug-

˙

higher stroke volume and Qt. Pressures are in mm Hg, and volumes are in mL.

gestive. As described above, the blood gas does not provide data which

is useful in discriminating patients with PE from those without. Plain

chest radiography can be helpful, in that only 12% of patients with PE

Of particular interest to the intensivist is the patient with a sublethal, have a normal film. The chest x-ray may demonstrate areas of oligemia

29

yet large, PE. With increased afterload, the right ventricle dilates to a (Westermark sign) and rare patients will develop a pleural based, trun-

larger end-diastolic volume. This is associated with elevated right atrial cated cone (Hampton hump); however, these “pathognomonic” signs are

and ventricular pressures and abnormally low Q ˙ t. One consequence poorly sensitive, and most films have only nonspecific findings. In fact,

29

of raised right atrial pressure is the potential for right-to-left shunting the greatest utility of the chest film is in making alternative diagnoses

across a probe patent foramen ovale, causing oxygen-refractory hypox- such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, or aortic dissection. Nevertheless,

emia. Intracardiac shunting could in turn allow paradoxical emboli- the typical (albeit nonspecific) findings of basilar atelectasis, elevation

zation of thrombus to the systemic arteries, with resultant stroke or of the diaphragm, and pleural effusion should always suggest PE when

systemic occlusive symptoms. The increase in right ventricular pressure there is no ready alternative explanation. Electrocardiography (ECG)

and volume also affects the left heart. A change in shape of the right may reveal signs of right heart strain such as rightward axis shift,

ventricle and corresponding shift of the interventricular septum from right bundle branch block, or right precordial strain but often shows

right to left alters the diastolic pressure-volume characteristics of the only sinus tachycardia. PE has also been described to cause coved ST

left ventricle (Fig. 39-4) and may be detected echocardiographically. elevation and Q waves anteriorly in the setting of a normal cardiac

The resultant fall in left ventricular (LV) compliance impairs diastolic angiogram, which resolved with anticoagulation. 30

filling, reducing LV preload and further limiting Q ˙ t. In experimental

models, reduced LV preload appears dependent on increased pericardial ■ SIGNS FROM MORE INVASIVE MONITORING

constraint as the pulmonary vascular resistance rises. 26,27 Increased peri- Valuable signs of PE may come from many of the devices used to

cardial constraint may explain why pulmonary artery occlusion pressure, monitor critically ill patients. The intensivist may derive clues from the

meant to approximate LV end-diastolic pressure, typically does not fall ventilator, expired gas analysis, the Pa catheter, or during echocardiogra-

during PE, and may be a poor indicator of LV preload. 26 phy. The sensitivity and specificity of these monitors for the diagnosis of

PE are not known. Nevertheless, by incorporating such data, clinicians

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS may alter their PE risk assessment and improve the benefit to risk ratio

■ HISTORY, EXAMINATION, AND LABORATORY DATA for subsequent testing and therapy.

Most patients with PE will complain of dyspnea, chest pain, and The Ventilator: To maintain P CO 2 , the patient with PE must augment

minute ventilation. Therefore, any unexplained increase in VE should

apprehension. 19,28 Less common symptoms are cough, diaphoresis, and prompt consideration of PE. Of course, any cause of rising dead space

hemoptysis. Up to 42% of subjects with PE will complain of leg or thigh (airflow obstruction, hypovolemia, PEEP) or increased CO produc-

symptoms, though in the PIOPED II registry, the same complaints were tion (anxiety, pain, fever, sepsis) will also increase VE. However, when

2

noted in 20% of subjects who did not have PE. Syncope is uncommon none of these conditions is apparent, especially when supporting clues

19

but described in all large series of PE (Table 39-1). are evident, PE becomes more likely.

The majority of patients will demonstrate tachypnea and tachycardia.

Pleural rub and signs of DVT are seen only occasionally. Fever is more Expired Carbon Dioxide: As described above, the increment in dead

common than is generally appreciated and seen in half the patients, but space after PE causes a detectable fall in ET . With technologic

28

CO 2

only rarely is the temperature greater than 38.5°C. Patients with large improvements in these devices, noninvasive assessment of expired

emboli may have the typical findings of any patient with low output CO is becoming increasingly practical in the ICU. A corollary of the

2

shock such as hypotension, narrow pulse pressure, and poor peripheral fall in ET with PE is that if VE does not rise (eg, in a muscle-relaxed

CO 2

perfusion. Occasionally, unanticipated failure to come off mechanical or highly sedated patient), the total excretion of CO (expired CO

2

2

ventilation or unexplained episodes of respiratory distress may be hints concentration × VE) must fall. Therefore, Pa CO 2 will rise progressively

section03.indd 321 1/23/2015 2:07:32 PM