Page 490 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 490

360 PART 3: Cardiovascular Disorders

the left, with no definite clot or embolus found at surgery should be

strongly suspected of having a dissection and investigated immediately.

A C

Unfortunately the physical findings classically associated with dissec-

tion are present in less than half of all cases, thereby necessitating a high

index of suspicion to save these patients. 32

INVESTIGATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS

■ LABORATORY

Laboratory data are usually within normal limits in patients with acute

dissection. The white blood cell count may be slightly elevated to 12,000

to 20,000/µL, most likely as a stress response. Electrocardiogram (ECG)

interpretation may show left ventricular hypertrophy due to chronic

hypertension, but other changes are rare. Acute ischemic changes

B D

should raise the concern of coronary artery involvement by the dissec-

tion in the patient with a typical history. Conversely, to avoid the dire

consequences of misdiagnosis, any patient presenting to the emergency

department with ECG changes suggesting myocardial ischemia (espe-

cially with evidence of right coronary artery involvement) should have

their history considered carefully before immediately moving to urgent

cardiac catheterization to treat the more prevalent condition of athero-

sclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD).

■ DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

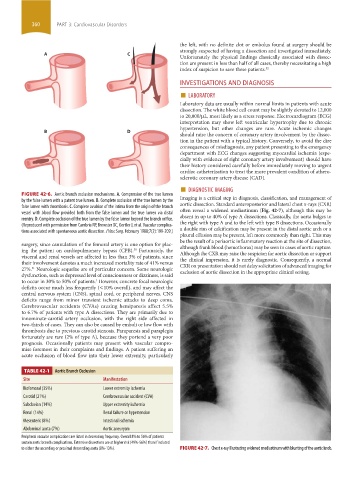

FIGURE 42-6. Aortic branch occlusion mechanisms. A. Compression of the true lumen Imaging is a critical step in diagnosis, classification, and management of

by the false lumen with a patent true lumen. B. Complete occlusion of the true lumen by the

false lumen with thrombosis. C. Complete avulsion of the intima from the origin of the branch aortic dissection. Standard anteroposterior and lateral chest x-rays (CXR)

often reveal a widened mediastinum (Fig. 42-7), although this may be

vessel with blood flow provided both from the false lumen and the true lumen via distal

reentry. D. Complete occlusion of the true lumen by the false lumen beyond the branch orifice. absent in up to 40% of type A dissections. Classically, the aorta bulges to

the right with type A and to the left with type B dissections. Occasionally

(Reproduced with permission from Cambria RP, Brewster DC, Gertler J, et al. Vascular complica-

tions associated with spontaneous aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. February 1988;7(2):199-209.) a double rim of calcification may be present in the distal aortic arch or a

pleural effusion may be present, left more commonly than right. This may

be the result of a periaortic inflammatory reaction at the site of dissection,

surgery, since cannulation of the femoral artery is one option for plac- although frank blood (hemothorax) may be seen in cases of aortic rupture.

ing the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Fortunately, the Although the CXR may raise the suspicion for aortic dissection or support

30

visceral and renal vessels are affected in less than 3% of patients, since the clinical impression, it is rarely diagnostic. Consequently, a normal

their involvement denotes a much increased mortality rate of 41% versus CXR on presentation should not delay solicitation of advanced imaging for

27%. Neurologic sequelae are of particular concern. Some neurologic exclusion of aortic dissection in the appropriate clinical setting.

31

dysfunction, such as depressed level of consciousness or dizziness, is said

to occur in 30% to 50% of patients. However, concrete focal neurologic

3

deficits occur much less frequently (<10% overall), and may affect the

central nervous system (CNS), spinal cord, or peripheral nerves. CNS

deficits range from minor transient ischemic attacks to deep coma.

Cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) causing hemiparesis affect 5.5%

to 6.7% of patients with type A dissections. They are primarily due to

innominate-carotid artery occlusion, with the right side affected in

two-thirds of cases. They can also be caused by emboli or low flow with

thrombosis due to previous carotid stenosis. Paraparesis and paraplegia

fortunately are rare (2% of type A), because they portend a very poor

prognosis. Occasionally patients may present with vascular compro-

mise foremost in their complaints and findings. A patient suffering an

acute occlusion of blood flow into their lower extremity, particularly

TABLE 42-1 Aortic Branch Occlusion

Site Manifestation

Iliofemoral (35%) Lower extremity ischemia

Carotid (21%) Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

Subclavian (14%) Upper extremity ischemia

Renal (14%) Renal failure or hypertension

Mesenteric (8%) Intestinal ischemia

Abdominal aorta (7%) Aortic aneurysm

Peripheral vascular complications are listed in decreasing frequency. Overall 8% to 56% of patients

sustain aortic branch complications. Extensive dissections are at higher risk (49%-56%) than if isolated

to either the ascending or proximal descending aorta (8%-13%). FIGURE 42-7. Chest x-ray illustrating widened mediastinum with blunting of the aortic knob.

section03.indd 360 1/23/2015 2:08:22 PM