Page 634 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 634

CHAPTER 52: Acute Lung Injury and the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome 453

progresses, there is extensive necrosis of type I alveolar epithelial cells. If in late-phase ARDS typically had a large dead space fraction, a high

the patient with ARDS does not recover or die during the first week, they minute ventilation requirement, progressive pulmonary hypertension,

may have a prolonged course of illness, termed late-phase ARDS. slightly improved intrapulmonary shunt that is less responsive to PEEP,

The later phase of ARDS is dominated by disordered healing. This can and a further reduction in lung compliance. 73

occur as early as 7 to 10 days after initial injury and may eventually result

in extensive pulmonary fibrosis. This has been termed the proliferative PATHOGENESIS

or fibroproliferative phase. Type II alveolar cells proliferate along alveolar

septae and the alveolar walls; fibroblasts and myofibroblasts become A number of closely interrelated pathophysiologic mechanisms and sys-

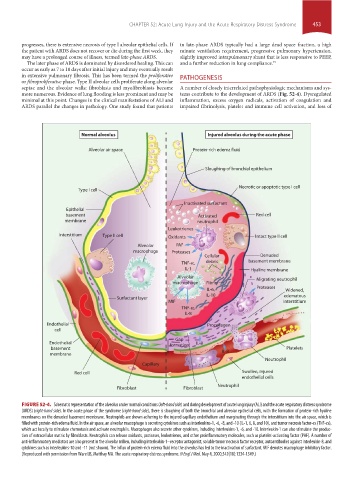

more numerous. Evidence of lung flooding is less prominent and may be tems contribute to the development of ARDS (Fig. 52-4). Dysregulated

minimal at this point. Changes in the clinical manifestations of ALI and inflammation, excess oxygen radicals, activation of coagulation and

ARDS parallel the changes in pathology. One study found that patients impaired fibrinolysis, platelet and immune cell activation, and loss of

Normal alveolus Injured alveolus during the acute phase

Alveolar air space Protein-rich edema fluid

Sloughing of bronchial epithelium

Necrotic or apoptotic type I cell

Type I cell

Inactivated surfactant

Epithelial

basement Activated Red cell

membrane neutrophil

Leukotrienes

Interstitium Type II cell Oxidants Intact type II cell

Alveolar PAF

macrophage Proteases

Cellular Denuded

TNF- , debris basement membrane

IL-1 Hyaline membrane

Alveolar Migrating neutrophil

macrophage Fibrin

IL-6, Proteases Widened,

IL-10 edematous

Surfactant layer

MIF interstitium

TNF- ,

IL-8

Endothelial Procollagen

cell

Gap

Endothelial formation IL-8

basement Platelets

membrane IL-8

Neutrophil

Capillary

Red cell Swollen, injured

endothelial cells

Neutrophil

Fibroblast Fibroblast

FIGURE 52-4. Schematic representation of the alveolus under normal conditions (left-hand side) and during development of acute lung injury (ALI) and the acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) (right-hand side). In the acute phase of the syndrome (right-hand side), there is sloughing of both the bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, with the formation of protein-rich hyaline

membranes on the denuded basement membrane. Neutrophils are shown adhering to the injured capillary endothelium and marginating through the interstitium into the air space, which is

filled with protein-rich edema fluid. In the air space, an alveolar macrophage is secreting cytokines such as interleukins-1, -6, -8, and -10 (IL-1, 6, 8, and 10), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α),

which act locally to stimulate chemotaxis and activate neutrophils. Macrophages also secrete other cytokines, including interleukins-1, -6, and -10. Interleukin-1 can also stimulate the produc-

tion of extracellular matrix by fibroblasts. Neutrophils can release oxidants, proteases, leukotrienes, and other proinflammatory molecules, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF). A number of

anti-inflammatory mediators are also present in the alveolar milieu, including interleukin-1–receptor antagonist, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor, autoantibodies against interleukin-8, and

cytokines such as interleukins-10 and -11 (not shown). The influx of protein-rich edema fluid into the alveolus has led to the inactivation of surfactant. MIF denotes macrophage inhibitory factor.

(Reproduced with permission from Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. May 4, 2000;342(18):1334-1349.)

section04.indd 453 1/23/2015 2:19:39 PM