Page 97 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 97

CHAPTER 10: Telemedicine and Regionalization 65

A

B

C D

A

B C

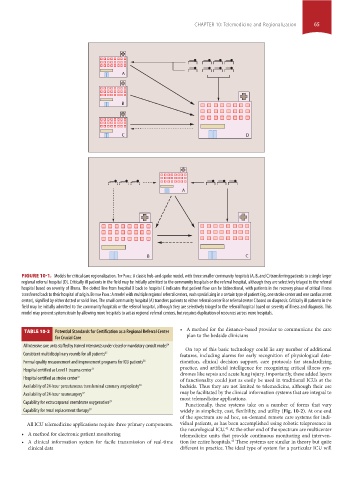

FIGURE 10-1. Models for critical care regionalization. Top panel: A classic hub-and-spoke model, with three smaller community hospitals (A, B, and C) transferring patients to a single larger

regional referral hospital (D). Critically ill patients in the field may be initially admitted to the community hospitals or the referral hospital, although they are selectively triaged to the referral

hospital based on severity of illness. The dotted line from hospital D back to hospital C indicates that patient flow can be bidirectional, with patients in the recovery phase of critical illness

transferred back to their hospital of origin. BoTTom panel: A model with multiple regional referral centers, each specializing in a certain type of patient (eg, one stroke center and one cardiac arrest

center), signified by either dotted or solid lines. The small community hospital (A) transfers patients to either referral center B or referral center C based on diagnosis. Critically ill patients in the

field may be initially admitted to the community hospitals or the referral hospital, although they are selectively triaged to the referral hospital based on severity of illness and diagnosis. This

model may prevent system strain by allowing more hospitals to act as regional referral centers, but requires duplication of resources across more hospitals.

• A method for the distance-based provider to communicate the care

TABLE 10-2 Potential Standards for Certification as a Regional Referral Center

for Crucial Care plan to the bedside clinicians

All intensive care units staffed by trained intensivists under closed or mandatory consult model 34

On top of this basic technology could lie any number of additional

Consistent multidisciplinary rounds for all patients 35 features, including alarms for early recognition of physiological dete-

Formal quality measurement and improvement programs for ICU patients 36 rioration, clinical decision support, care protocols for standardizing

Hospital certified as Level 1 trauma center 11 practice, and artificial intelligence for recognizing critical illness syn-

dromes like sepsis and acute lung injury. Importantly, these added layers

Hospital certified as stroke center 37 of functionality could just as easily be used in traditional ICUs at the

Availability of 24-hour percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty 38 bedside. Thus they are not limited to telemedicine, although their use

Availability of 24-hour neurosurgery 37 may be facilitated by the clinical information systems that are integral to

most telemedicine applications.

Capability for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation 23 Functionally, these systems take on a number of forms that vary

Capability for renal replacement therapy 39 widely in simplicity, cost, flexibility, and utility (Fig. 10-2). At one end

of the spectrum are ad hoc, on-demand remote care systems for indi-

All ICU telemedicine applications require three primary components. vidual patients, as has been accomplished using robotic telepresence in

42

the neurological ICU. At the other end of the spectrum are multicenter

• A method for electronic patient monitoring telemedicine units that provide continuous monitoring and interven-

43

• A clinical information system for facile transmission of real-time tion for entire hospitals. These systems are similar in theory but quite

clinical data different in practice. The ideal type of system for a particular ICU will

Section01.indd 65 1/22/2015 9:37:08 AM