Page 645 - Williams Hematology ( PDFDrive )

P. 645

620 Part VI: The Erythrocyte Chapter 42: Iron Metabolism 621

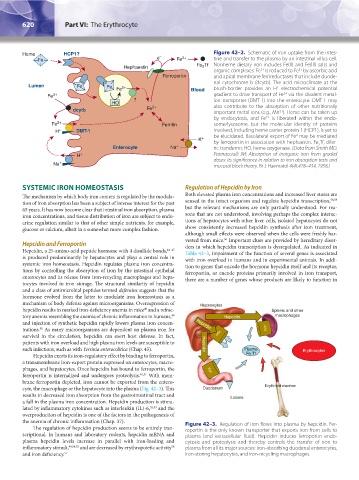

Heme HCP1? – Figure 42–2. Schematic of iron uptake from the intes-

Fe e Fe 3+ tine and transfer to the plasma by an intestinal villus cell.

Hephaestin Fe Tf Nonheme dietary iron includes Fe(II) and Fe(III) salts and

2

organic complexes. Fe is reduced to Fe by ascorbic acid

3+

2+

Ferroportin and apical membrane ferrireductases that include duode-

nal cytochrome b (dcytb). The acid microclimate at the

Lumen Fe Fe Fe 2+ Blood brush-border provides an H electrochemical potential

+

2+

Fe 3+ gradient to drive transport of Fe via the divalent metal-

HO ? ion transporter (DMT-1) into the enterocyte. DMT-1 may

also contribute to the absorption of other nutritionally

dcytb Fe 2+ important metal ions (e.g., Mn ). Heme can be taken up

2+

by endocytosis, and Fe is liberated within the endo-

2+

Fe 2+ Ferritin some/lysosome, but the molecular identity of proteins

H + DMT-1 involved, including heme carrier protein 1 (HCP1), is yet to

be elucidated. Basolateral export of Fe may be mediated

2

K + by ferroportin in association with hephaestin. Fe Tf, difer-

2

Enterocyte Na + ric transferrin; HO, heme oxygenase. (Data from Smith MD,

H + Pannacciulli IM: Absorption of inorganic iron from graded

doses: its significance in relation to iron absorption tests and

Na + mucosal block theory. Br J Haematol 4(4):428–434, 1958.)

SYSTEMIC IRON HOMEOSTASIS Regulation of Hepcidin by Iron

The mechanism by which body iron content is regulated by the modula- Both elevated plasma iron concentrations and increased liver stores are

tion of iron absorption has been a subject of intense interest for the past sensed in the intact organism and regulate hepcidin transcription, 58,59

65 years. It has now become clear that intestinal iron absorption, plasma but the relevant mechanisms are only partially understood. For rea-

iron concentrations, and tissue distribution of iron are subject to endo- sons that are not understood, involving perhaps the complex interac-

crine regulation similar to that of other simple nutrients, for example, tions of hepatocytes with other liver cells, isolated hepatocytes do not

glucose or calcium, albeit in a somewhat more complex fashion. show consistently increased hepcidin synthesis after iron treatment,

although small effects were observed when the cells were freshly har-

vested from mice. Important clues are provided by hereditary disor-

60

Hepcidin and Ferroportin ders in which hepcidin transcription is dysregulated. As indicated in

Hepcidin, a 25-amino-acid peptide hormone with 4 disulfide bonds, 44–47 Table 42–3, impairment of the function of several genes is associated

is produced predominantly by hepatocytes and plays a central role in with iron overload in humans and in experimental animals. In addi-

systemic iron homeostasis. Hepcidin regulates plasma iron concentra- tion to genes that encode the hormone hepcidin itself and its receptor,

tions by controlling the absorption of iron by the intestinal epithelial ferroportin, or encode proteins primarily involved in iron transport,

enterocytes and its release from iron-recycling macrophages and hepa- there are a number of genes whose products are likely to function in

tocytes involved in iron storage. The structural similarity of hepcidin

and a class of antimicrobial peptides termed defensins suggests that the

hormone evolved from the latter to modulate iron homeostasis as a

mechanism of body defense against microorganisms. Overexpression of Hepatocytes

hepcidin results in marked iron-deficiency anemia in mice and a refrac- Splenic and other

48

tory anemia resembling the anemia of chronic inflammation in humans, Hepcidin macrophages

49

and injection of synthetic hepcidin rapidly lowers plasma iron concen- Hepcidin

trations. As many microorganisms are dependent on plasma iron for Fpn

50

survival in the circulation, hepcidin can exert host defense. In fact, Fpn

patients with iron overload and high plasma iron levels are susceptible to Hepcidin

such infections, such as with Yersinia enterocolitica (Chap. 43). Plasma Erythrocytes

Hepcidin exerts its iron-regulatory effect by binding to ferroportin, Fe-Tf

a transmembrane iron-export protein expressed on enterocytes, macro-

phages, and hepatocytes. Once hepcidin has bound to ferroportin, the Fpn

ferroportin is internalized and undergoes proteolysis. 40,51 With mem-

brane ferroportin depleted, iron cannot be exported from the entero-

cyte, the macrophage or the hepatocyte into the plasma (Fig. 42–3). This Duodenum Erythroid marrow

results in decreased iron absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and Losses

a fall in the plasma iron concentration. Hepcidin production is stimu-

lated by inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, 52,53 and the

overproduction of hepcidin is one of the factors in the pathogenesis of

the anemia of chronic inflammation (Chap. 37). Figure 42–3. Regulation of iron flows into plasma by hepcidin. Fer-

The regulation of hepcidin production seems to be entirely tran- roportin is the only known transporter that exports iron from cells to

scriptional. In humans and laboratory rodents, hepcidin mRNA and plasma (and extracellular fluid). Hepcidin induces ferroportin endo-

plasma hepcidin levels increase in parallel with iron-loading and cytosis and proteolysis and thereby controls the transfer of iron to

inflammatory stimuli, 44,54,55 and are decreased by erythropoietic activity plasma from all its major sources: iron-absorbing duodenal enterocytes,

56

and iron deficiency. 57 iron-storing hepatocytes, and iron-recycling macrophages.

Kaushansky_chapter 42_p0617-0626.indd 620 9/17/15 6:26 PM