Page 649 - Williams Hematology ( PDFDrive )

P. 649

624 Part VI: The Erythrocyte Chapter 42: Iron Metabolism 625

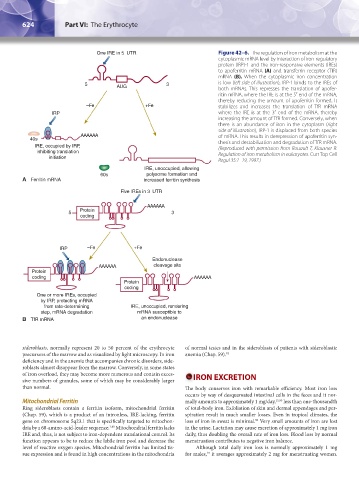

One IRE in 5 UTR Figure 42–6. The regulation of iron metabolism at the

cytoplasmic mRNA level by interaction of iron-regulatory

protein (IRP)-1 and the iron-responsive elements (IREs)

to apoferritin mRNA (A) and transferrin receptor (TfR)

mRNA (B). When the cytoplasmic iron concentration

5 AUG 3 is low (left side of illustration), IRP-1 binds to the IREs of

both mRNAs. This represses the translation of apofer-

ritin mRNA, where the IRE is at the 5′ end of the mRNA,

thereby reducing the amount of apoferritin formed. It

–Fe +Fe stabilizes and increases the translation of TfR mRNA

IRP where the IRE is at the 3′ end of the mRNA, thereby

increasing the amount of TfR formed. Conversely, when

there is an abundance of iron in the cytoplasm (right

side of illustration), IRP-1 is displaced from both species

AAAAAA of mRNA. This results in derepression of apoferritin syn-

40s thesis and destabilization and degradation of TfR mRNA.

IRE, occupied by IRP, (Reproduced with permission from Rouault T, Klausner R:

inhibiting translation Regulation of iron metabolism in eukaryotes. Curr Top Cell

initiation

Regul 35:1–19, 1997.)

IRE, unoccupied, allowing

60s polysome formation and

A Ferritin mRNA increased ferritin synthesis

Five IREs in 3 UTR

AAAAAA

5 Protein 3

coding

IRP –Fe +Fe

Endonuclease

AAAAAA cleavage site

Protein

coding AAAAAA

Protein

coding

One or more IREs, occupied

by IRP, protecting mRNA

from rate-determining IRE, unoccupied, rendering

step, mRNA degradation mRNA susceptible to

B TfR mRNA an endonuclease

sideroblasts, normally represent 20 to 50 percent of the erythrocyte of normal testes and in the sideroblasts of patients with sideroblastic

precursors of the marrow and as visualized by light microscopy. In iron anemia (Chap. 59). 92

deficiency and in the anemia that accompanies chronic disorders, side-

roblasts almost disappear from the marrow. Conversely, in some states

of iron overload, they may become more numerous and contain exces- IRON EXCRETION

sive numbers of granules, some of which may be considerably larger

than normal. The body conserves iron with remarkable efficiency. Most iron loss

occurs by way of desquamated intestinal cells in the feces and it nor-

Mitochondrial Ferritin mally amounts to approximately 1 mg/day, 15,93 less than one-thousandth

Ring sideroblasts contain a ferritin isoform, mitochondrial ferritin of total-body iron. Exfoliation of skin and dermal appendages and per-

(Chap. 59), which is a product of an intronless, IRE-lacking, ferritin spiration result in much smaller losses. Even in tropical climates, the

gene on chromosome 5q23.1 that is specifically targeted to mitochon- loss of iron in sweat is minimal. Very small amounts of iron are lost

90

dria by a 60-amino-acid-leader sequence. Mitochondrial ferritin lacks in the urine. Lactation may cause excretion of approximately 1 mg iron

1,91

IRE and, thus, is not subject to iron-dependent translational control. Its daily, thus doubling the overall rate of iron loss. Blood loss by normal

function appears to be to reduce the labile iron pool and decrease the menstruation contributes to negative iron balance.

level of reactive oxygen species. Mitochondrial ferritin has limited tis- Although total daily iron loss is normally approximately 1 mg

sue expression and is found in high concentrations in the mitochondria for males, it averages approximately 2 mg for menstruating women.

15

Kaushansky_chapter 42_p0617-0626.indd 624 9/17/15 6:26 PM