Page 170 - 9780077418427.pdf

P. 170

/Users/user-f465/Desktop

tiL12214_ch06_139-176.indd Page 147 9/1/10 9:40 PM user-f465

tiL12214_ch06_139-176.indd Page 147 9/1/10 9:40 PM user-f465 /Users/user-f465/Desktop

joules/coulomb, or volts (equation 6.3). The source of the electri-

cal potential difference is therefore referred to as a voltage source.

The device where the charges do their work causes a voltage drop.

Electrical potential difference is measured in volts, so the term

Upper voltage is often used for it. Household circuits usually have a dif-

reservoir ference of potential of 120 or 240 volts. A voltage of 120 volts

means that each coulomb of charge that moves through the cir-

Pump cuit can do 120 joules of work in some electrical device.

Voltage describes the potential difference, in joules per cou-

Waterwheel lomb, between two places in an electric circuit. By way of anal-

ogy to pressure on water in a circuit of water pipes, this potential

difference is sometimes called an electrical force or electromotive

force (emf). Note that in electrical matters, however, the potential

difference is the source of a force rather than being a force such as

water under pressure. Nonetheless, just as you can have a small

Lower reservoir water pipe and a large water pipe under the same pressure, the

two pipes would have a different rate of water flow in gallons per

FIGURE 6.9 The falling water can do work in turning the water- minute. Electric current (I) is the rate at which charge (q) fl ows

wheel only as long as the pump maintains the potential difference through a cross section of a conductor in a unit of time (t), or

between the upper and lower reservoirs.

quantity of charge

__

electric current =

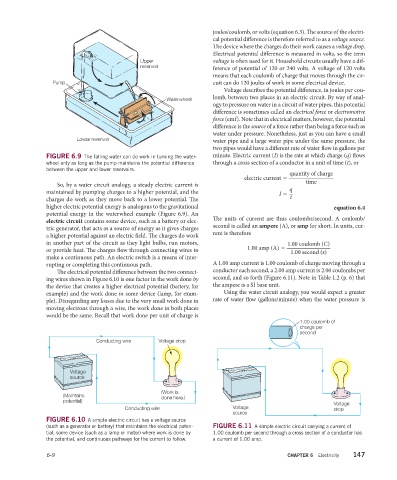

So, by a water circuit analogy, a steady electric current is time

q

_

maintained by pumping charges to a higher potential, and the I =

charges do work as they move back to a lower potential. Th e t

higher electric potential energy is analogous to the gravitational equation 6.4

potential energy in the waterwheel example (Figure 6.9). An

The units of current are thus coulombs/second. A coulomb/

electric circuit contains some device, such as a battery or elec-

second is called an ampere (A), or amp for short. In units, cur-

tric generator, that acts as a source of energy as it gives charges

rent is therefore

a higher potential against an electric fi eld. The charges do work

in another part of the circuit as they light bulbs, run motors, __

1.00 coulomb (C)

or provide heat. The charges flow through connecting wires to 1.00 amp (A) = 1.00 second (s)

make a continuous path. An electric switch is a means of inter-

rupting or completing this continuous path. A 1.00 amp current is 1.00 coulomb of charge moving through a

The electrical potential difference between the two connect- conductor each second, a 2.00 amp current is 2.00 coulombs per

ing wires shown in Figure 6.10 is one factor in the work done by second, and so forth (Figure 6.11). Note in Table 1.2 (p. 6) that

the device that creates a higher electrical potential (battery, for the ampere is a SI base unit.

example) and the work done in some device (lamp, for exam- Using the water circuit analogy, you would expect a greater

ple). Disregarding any losses due to the very small work done in rate of water flow (gallons/minute) when the water pressure is

moving electrons through a wire, the work done in both places

would be the same. Recall that work done per unit of charge is

1.00 coulomb of

charge per

second

Conducting wire Voltage drop

Voltage

source

(Work is

(Maintains done here.)

potential) Voltage

Conducting wire Voltage drop

source

FIGURE 6.10 A simple electric circuit has a voltage source

(such as a generator or battery) that maintains the electrical poten- FIGURE 6.11 A simple electric circuit carrying a current of

tial, some device (such as a lamp or motor) where work is done by 1.00 coulomb per second through a cross section of a conductor has

the potential, and continuous pathways for the current to follow. a current of 1.00 amp.

6-9 CHAPTER 6 Electricity 147