Page 584 - Cardiac Nursing

P. 584

6/2

009

6/2

0/0

0/0

1:4

1:4

0

009

0

3

q

q

94.

5-5

94.

3

3

xd

q

xd

3 P

p

p

A

60

A

ara

ara

t

p

t

60

Pa

Pa

M

3 P

M

e 5

e 5

g

g

g

5-5

p

55

55

24_

0-c

K34

LWBK340-c24_

LWB K34 0-c 24_ p pp555-594.qxd 30/06/2009 01:43 PM Page 560 Aptara

LWB

560 PA R T I V / Pathophysiology and Management of Heart Disease

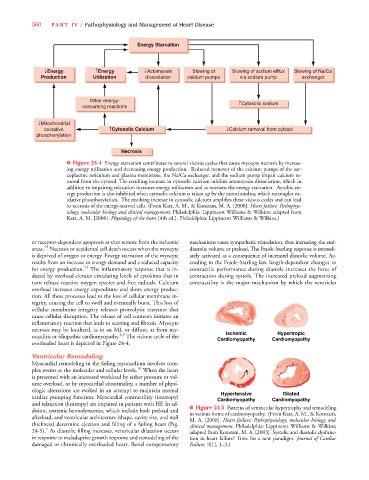

Energy Starvation

↓Energy ↑Energy ↓Actomyosin Slowing of Slowing of sodium efflux Slowing of Na/Ca

Production Utilization dissociation calcium pumps via sodium pump exchanger

Other energy-

↑Cytosolic sodium

consuming reactions

↓Mitochondrial

oxidative ↑Cytosolic Calcium ↓Calcium removal from cytosol

phosphorylation

Necrosis

■ Figure 24-4 Energy starvation contributes to several vicious cycles that cause myocyte necrosis by increas-

ing energy utilization and decreasing energy production. Reduced turnover of the calcium pumps of the sar-

coplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane, the Na/Ca exchanger, and the sodium pump impair calcium re-

moval from the cytosol. The resulting increase in cytosolic calcium inhibits actomyosin dissociation, which in

addition to impairing relaxation increases energy utilization and so worsens the energy starvation. Aerobic en-

ergy production is also inhibited when cytosolic calcium is taken up by the mitochondria, which uncouples ox-

idative phosphorylation. The resulting increase in cytosolic calcium amplifies these vicious cycles and can lead

to necrosis of the energy-starved cells. (From Katz, A. M., & Konstam, M. A. [2008]. Heart failure: Pathophys-

iology, molecular biology and clinical management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; adapted from

Katz, A. M. [2006]. Physiology of the heart [4th ed.]. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

or receptor-dependent apoptosis at sites remote from the ischemic mechanisms cause sympathetic stimulation, thus increasing the end-

15

areas. Necrosis or accidental cell death occurs when the myocyte diastolic volume or preload. The Frank–Starling response is immedi-

is deprived of oxygen or energy. Energy starvation of the myocyte ately activated as a consequence of increased diastolic volume. Ac-

results from an increase in energy demand and a reduced capacity cording to the Frank–Starling law, length-dependent changes in

for energy production. 11 The inflammatory response that is in- contractile performance during diastole increases the force of

duced by overload elevates circulating levels of cytokines that in contraction during systole. The increased preload augmenting

turn release reactive oxygen species and free radicals. Calcium contractility is the major mechanism by which the ventricles

overload increases energy expenditure and slows energy produc-

tion. All these processes lead to the loss of cellular membrane in-

tegrity, causing the cell to swell and eventually burst. This loss of

cellular membrane integrity releases proteolytic enzymes that

cause cellular disruption. The release of cell contents initiates an

inflammatory reaction that leads to scarring and fibrosis. Myocyte

necrosis may be localized, as in an MI, or diffuse, as from my- Ischemic Hypertropic

ocarditis or idiopathic cardiomyopathy. 6,7 The vicious cycle of the Cardiomyopathy Cardiomyopathy

overloaded heart is depicted in Figure 24-4.

Ventricular Remodeling

Myocardial remodeling in the failing myocardium involves com-

plex events at the molecular and cellular levels. 16 When the heart

is presented with an increased workload by either pressure or vol-

ume overload, or by myocardial abnormality, a number of physi-

ologic alterations are evoked in an attempt to maintain normal Hypertensive Dilated

cardiac pumping function. Myocardial contractility (inotropy) Cardiomyopathy Cardiomyopathy

and relaxation (lusitropy) are impaired in patients with HF. In ad-

dition, systemic hemodynamics, which include both preload and ■ Figure 24-5 Patterns of ventricular hypertrophy and remodeling

in various forms of cardiomyopathy. (From Katz, A. M., & Konstam,

afterload, and ventricular architecture (shape, cavity size, and wall M. A. [2008]. Heart failure: Pathophysiology, molecular biology and

thickness) determine ejection and filling of a failing heart (Fig. clinical management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

7

24-5). As diastolic filling increases, ventricular dilatation occurs adapted from Konstam, M. A. [2003]. Systolic and diastolic dysfunc-

in response to maladaptive growth response and remodeling of the tion in heart failure? Time for a new paradigm. Journal of Cardiac

damaged or chronically overloaded heart. Renal compensatory Failure, 9[1], 1–3.)