Page 505 - 9780077418427.pdf

P. 505

/Users/user-f465/Desktop

tiL12214_ch19_477-500.indd Page 482 9/3/10 6:22 PM user-f465

tiL12214_ch19_477-500.indd Page 482 9/3/10 6:22 PM user-f465 /Users/user-f465/Desktop

FAULTING Direction of

Rock layers do not always respond to stress by folding. Rocks near dip of fault Strike of fault

the surface are cooler and under less pressure, so they tend to

be more brittle. A sudden stress on these rocks may reach the

rupture point, resulting in a cracking and breaking of the rock

structure. If there is breaking of rock without a relative displace-

ment on either side of the break, the crack is called a joint. Joints Ore vein

Hanging wall

Footwall

are common in rocks exposed at the surface of Earth. They can be block along fault block

produced from compressional stresses, but they are also formed

by other processes such as the contraction of an igneous rock Hanging

while cooling. Basalt often develops columnar jointing from the wall

contraction of cooling, solidified magma. The joints are parallel Footwall

and evenly spaced, resulting in the appearance of hexagonal col-

umns (Figure 19.8). The Devil’s Post Pile in California and Devil’s A

Tower in Wyoming are classic examples of columnar jointing.

When there is relative movement between the rocks on either

side of a fracture, the crack is called a fault. When faulting occurs,

the rocks on one side move relative to the rocks on the other side

along the surface of the fault, which is called the fault plane. Faults

are generally described in terms of (1) the steepness of the fault

plane, that is, the angle between the plane and an imaginary hori-

zontal plane, and (2) the direction of relative movement. There

are basically three ways that rocks on one side of a fault can move

relative to the rocks on the other side: (1) up and down (called

dip), (2) horizontally, or sideways (called strike), and (3) with ele-

ments of both directions of movement (called oblique).

One classification scheme for faults is based on an ori-

entation referent borrowed from mining (many ore veins are

associated with fault planes). Imagine a mine with a fault plane

running across a horizontal shaft. Unless the plane is perfectly

vertical, a miner would stand on the mass of rock below the

fault plane and look up at the mass of rock above. Therefore,

B

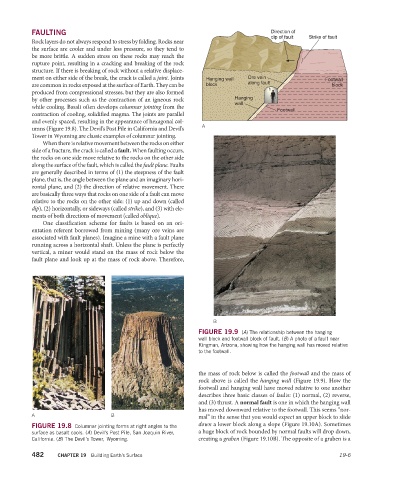

FIGURE 19.9 (A) The relationship between the hanging

wall block and footwall block of fault. (B) A photo of a fault near

Kingman, Arizona, showing how the hanging wall has moved relative

to the footwall.

the mass of rock below is called the footwall and the mass of

rock above is called the hanging wall (Figure 19.9). How the

footwall and hanging wall have moved relative to one another

describes three basic classes of faults: (1) normal, (2) reverse,

and (3) thrust. A normal fault is one in which the hanging wall

has moved downward relative to the footwall. This seems “nor-

A B mal” in the sense that you would expect an upper block to slide

down a lower block along a slope (Figure 19.10A). Sometimes

FIGURE 19.8 Columnar jointing forms at right angles to the

surface as basalt cools. (A) Devil’s Post Pile, San Joaquin River, a huge block of rock bounded by normal faults will drop down,

California. (B) The Devil’s Tower, Wyoming. creating a graben (Figure 19.10B). The opposite of a graben is a

482 CHAPTER 19 Building Earth’s Surface 19-6