Page 315 - (DK) Ocean - The Definitive Visual Guide

P. 315

SMALL, BOTTOM-LIVING PHYLA 313

Small, Bottom-living Phyla

MANY DISPARATE INVERTEBRATES play important parts in marine ecosystems but

DOMAIN Eucarya

are seldom seen, because they are small or their habitats are difficult to study. Like

KINGDOM Animalia

all animals, they are grouped into phyla, each phylum representing an apparently

PHYLA 10

distinct body plan. Most of these small, bottom-living phyla live in seabed sediment

SPECIES Many

and are loosely called “worms” due to their shape and burrowing lifestyle.

However, the superabundant nematodes or roundworms of which there are 28,000 described species and

possibly a million in total, live in a wide range of environments, including

the seabed. A selection of 10 bottom-living phyla are represented below.

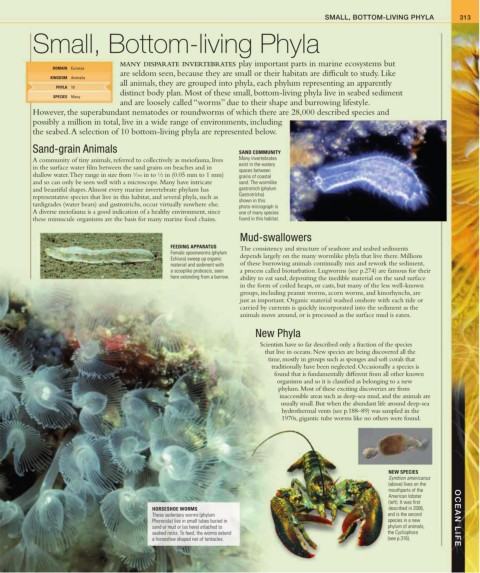

Sand-grain Animals SAND COMMUNITY

A community of tiny animals, referred to collectively as meiofauna, lives Many invertebrates

in the surface water film between the sand grains on beaches and in exist in the watery

spaces between

1

1

shallow water. They range in size from / 100 in to / 2 in (0.05 mm to 1 mm) grains of coastal

and so can only be seen well with a microscope. Many have intricate sand. The wormlike

and beautiful shapes. Almost every marine invertebrate phylum has gastrotrich (phylum

representative species that live in this habitat, and several phyla, such as Gastrotricha)

shown in this

tardigrades (water bears) and gastrotrichs, occur virtually nowhere else. photo-micrograph is

A diverse meiofauna is a good indication of a healthy environment, since one of many species

these minuscule organisms are the basis for many marine food chains. found in this habitat.

Mud-swallowers

FEEDING APPARATUS The consistency and structure of seashore and seabed sediments

Female spoonworms (phylum

Echiura) sweep up organic depends largely on the many wormlike phyla that live there. Millions

material and sediment with of these burrowing animals continually mix and rework the sediment,

a scooplike proboscis, seen a process called bioturbation. Lugworms (see p.274) are famous for their

here extending from a burrow. ability to eat sand, depositing the inedible material on the sand surface

in the form of coiled heaps, or casts, but many of the less well-known

groups, including peanut worms, acorn worms, and kinorhynchs, are

just as important. Organic material washed onshore with each tide or

carried by currents is quickly incorporated into the sediment as the

animals move around, or is processed as the surface mud is eaten.

New Phyla

Scientists have so far described only a fraction of the species

that live in oceans. New species are being discovered all the

time, mostly in groups such as sponges and soft corals that

traditionally have been neglected. Occasionally a species is

found that is fundamentally different from all other known

organisms and so it is classified as belonging to a new

phylum. Most of these exciting discoveries are from

inaccessible areas such as deep-sea mud, and the animals are

usually small. But when the abundant life around deep-sea

hydrothermal vents (see p.188–89) was sampled in the

1970s, gigantic tube worms like no others were found.

NEW SPECIES

Symbion americanus

(above) lives on the

mouthparts of the

American lobster

(left). It was first

HORSESHOE WORMS described in 2006,

These sedentary worms (phylum and is the second

Phoronida) live in small tubes buried in species in a new OCEAN LIFE

sand or mud or (as here) attached to phylum of animals,

seabed rocks. To feed, the worms extend the Cycliophora

a horseshoe shaped net of tentacles. (see p.316).