Page 112 - Hall et al (2015) Principles of Critical Care-McGraw-Hill

P. 112

80 PART 1: An Overview of the Approach to and Organization of Critical Care

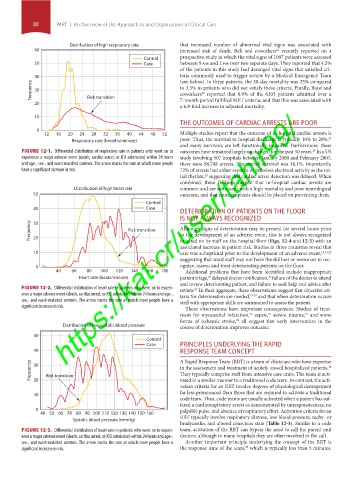

Distribution of high respiratory rate that increased number of abnormal vital signs was associated with

60 increased risk of death. Bell and coworkers recently reported on a

21

Control prospective study in which the vital signs of 1097 patients were assessed

50 Case between 9 am and 2 pm over two separate days. They reported that 4.5%

of the patients in this study had deranged vital signs that satisfied cri-

40 teria commonly used to trigger review by a Medical Emergency Team

(see below). In these patients, the 30-day mortality was 25% compared

Frequency 30 Risk transition to 3.5% in patients who did not satisfy these criteria. Finally, Buist and

coworkers reported that 8.9% of the 6303 patients admitted over a

22

20 7-month period fulfilled MET criteria, and that this was associated with

a 6.8-fold increase in adjusted mortality.

10

THE OUTCOMES OF CARDIAC ARRESTS ARE POOR

0 Multiple studies report that the outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrests is

12 16 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 52

23

Respiratory rate (breaths/minute) poor. Thus, the survival to hospital discharge is typically 10% to 20%,

and many survivors are left functionally impaired. Furthermore, these

FIGURE 12-1. Differential distribution of respiratory rate in patients who went on to outcomes have remained largely unchanged for the past 50 years. In a US

24

experience a major adverse event (death, cardiac arrest, or ICU admission) within 24 hours study involving 507 hospitals between January 2000 and February 2007,

and age-, sex-, and ward-matched controls. The arrow marks the rate at which more people there were 86,748 arrests. The overall survival was 18.1%. Importantly,

have a significant increase in risk. 72% of arrests had either asystole or pulseless electrical activity as the ini-

tial rhythm, suggesting that cardiac arrest detection was delayed. When

23

combined, these findings suggest that in-hospital cardiac arrests are

Distribution of high heart rate common and are associated with a high mortality and poor neurological

50 outcome, and that more emphasis should be placed on preventing them.

Control

40 Case

DETERIORATION OF PATIENTS ON THE FLOOR

IS NOT ALWAYS RECOGNIZED

Frequency 20 https://kat.cr/user/tahir99/

30

Although signs of deterioration may be present for several hours prior

Risk transition

to the development of an adverse event, this is not always recognized

or acted on by staff on the hospital floor (Figs. 12-4 and 12-5) with an

associated increase in patient risk. Studies in three countries reveal that

10 care was suboptimal prior to the development of an adverse event, 15,19,22

suggesting that ward staff may not have the skill set or resources to rec-

0 ognize, assess, and treat deteriorating patients on the floor.

40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 Additional problems that have been identified include inappropriate

Heart rate (beats/minute) patient triage, delayed doctor notification, failure of the doctor to attend

25

26

and review deteriorating patient, and failure to seek help and advice after

FIGURE 12-2. Differential distribution of heart rate in patients who went on to experi- review. In their aggregate, these observations suggest that objective cri-

27

ence a major adverse event (death, cardiac arrest, or ICU admission) within 24 hours and age-, teria for deterioration are needed, 27-29 and that when deterioration occurs

sex-, and ward-matched controls. The arrow marks the rate at which more people have a staff with appropriate skills are summoned to assess the patient.

significant increase in risk.

These observations have important consequences. Studies of treat-

ment for myocardial infarction, sepsis, severe trauma, and some

30

32

31

forms of ischemic stroke, all suggest that early intervention in the

33

Distribution of low systolic blood pressure course of deterioration improves outcome.

50

Control

Case PRINCIPLES UNDERLYING THE RAPID

40 RESPONSE TEAM CONCEPT

Frequency 30 Risk transition A Rapid Response Team (RRT) is a team of clinicians who have expertise

in the assessment and treatment of acutely unwell hospitalized patients.

34

They typically comprise staff from intensive care units. The team is acti-

vated in a similar manner to a traditional code team. In contrast, the acti-

20

vation criteria for an RRT involve degrees of physiological derangement

far less pronounced than those that are required to activate a traditional

10

code team. Thus, code teams are usually activated when a patient has suf-

fered a cardiorespiratory arrest as demonstrated by unresponsiveness, no

0 palpable pulse, and absence of respiratory effort. Activation criteria for an

40 50 60 70 80 90 100110 120130 140150 160 RRT typically involve respiratory distress, low blood pressure, tachy- or

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)

bradycardia, and altered conscious state (Table 12-3). Similar to a code

FIGURE 12-3. Differential distribution of heart rate in patients who went on to experi- team, activation of the RRT can bypass the need to call the parent unit

ence a major adverse event (death, cardiac arrest, or ICU admission) within 24 hours and age-, doctors, although in many hospitals they are often involved in the call.

sex-, and ward-matched controls. The arrow marks the rate at which more people have a Another important principle underlying the concept of the RRT is

35

significant increase in risk. the response time of the team, which is typically less than 5 minutes.

Section01.indd 80 1/22/2015 9:37:18 AM