Page 2129 - Williams Hematology ( PDFDrive )

P. 2129

2104 Part XII: Hemostasis and Thrombosis Chapter 122: The Vascular Purpuras 2105

Persistent purpura, severe abdominal symptoms, and diminished

plasma coagulation factor XIII activity are predictive of renal involve-

ment, requiring initiation of glucocorticoids. 85

INFECTIONS

Careful analysis of skin lesions of infectious etiology can provide

important hints toward identifying the responsible pathogen. Purpura

can arise through a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms associ-

ated with infection: (1) vascular effects of toxins, (2) septic emboli,

(3) direct invasion of vessels with subsequent vascular occlusion, and

(4) immune complex formation. Although the morphology of such

86

purpuric lesions may be nonspecific, many pathogens lead to charac-

teristic findings.

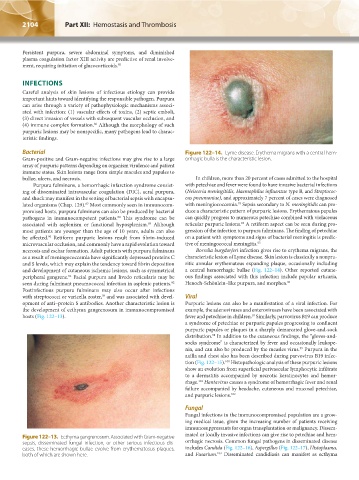

Bacterial Figure 122–14. Lyme disease. Erythema migrans with a central hem-

Gram-positive and Gram-negative infections may give rise to a large orrhagic bulla is the characteristic lesion.

array of purpuric patterns depending on organism virulence and patient

immune status. Skin lesions range from simple macules and papules to

bullae, ulcers, and necrosis. In children, more than 20 percent of cases admitted to the hospital

Purpura fulminans, a hemorrhagic infarction syndrome consist- with petechiae and fever were found to have invasive bacterial infections

ing of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acral purpura, (Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and Streptococ-

and shock may manifest in the setting of bacterial sepsis with encapsu- cus pneumoniae), and approximately 7 percent of cases were diagnosed

93

lated organisms (Chap. 129). Most commonly seen in immunocom- with meningiococcemia. Sepsis secondary to N. meningitidis can pro-

87

promised hosts, purpura fulminans can also be produced by bacterial duce a characteristic pattern of purpuric lesions. Erythematous papules

pathogens in immunocompetent patients. This syndrome can be can quickly progress to numerous petechiae combined with violaceous

88

associated with asplenism or functional hyposplenism. Although reticular purpuric lesions. A retiform aspect can be seen during pro-

94

89

most patients are younger than the age of 10 years, adults can also gression of the infection to purpura fulminans. The finding of petechiae

be affected. Retiform purpuric lesions result from fibrin-induced on a patient with symptoms and signs of bacterial meningitis is predic-

90

microvascular occlusion, and commonly have a rapid evolution toward tive of meningococcal meningitis. 95

necrosis and eschar formation. Adult patients with purpura fulminans Borrelia burgdorferi infection gives rise to erythema migrans, the

as a result of meningococcemia have significantly depressed proteins C characteristic lesion of Lyme disease. Skin lesion is classically a nonpru-

and S levels, which may explain the tendency toward fibrin deposition ritic annular erythematous expanding plaque, occasionally including

and development of cutaneous ischemic lesions, such as symmetrical a central hemorrhagic bullae (Fig. 122–14). Other reported cutane-

peripheral gangrene. Facial purpura and livedo reticularis may be ous findings associated with this infection include papular urticaria,

91

seen during fulminant pneumococcal infection in asplenic patients. Henoch-Schönlein–like purpura, and morphea. 96

92

Postinfectious purpura fulminans may also occur after infections

with streptococci or varicella zoster, and was associated with devel- Viral

39

opment of anti–protein S antibodies. Another characteristic lesion is Purpuric lesions can also be a manifestation of a viral infection. For

the development of ecthyma gangrenosum in immunocompromised example, the adenoviruses and enteroviruses have been associated with

hosts (Fig. 122–13). fever and petechiae in children. Similarly, parvovirus B19 can produce

97

a syndrome of petechiae or purpuric papules progressing to confluent

purpuric papules or plaques in a sharply demarcated glove-and-sock

distribution. In addition to the cutaneous findings, the “gloves-and-

98

socks syndrome” is characterized by fever and occasionally leukope-

nia, and can also be produced by the measles virus. Purpura in the

99

axilla and chest also has been described during parvovirus B19 infec-

tion (Fig. 122–15). Histopathologic analysis of these purpuric lesions

100

show an evolution from superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate

to a dermatitis accompanied by necrotic keratinocytes and hemor-

rhage. Hantavirus causes a syndrome of hemorrhagic fever and renal

101

failure accompanied by headache, cutaneous and mucosal petechiae,

and purpuric lesions. 102

Fungal

Fungal infections in the immunocompromised population are a grow-

ing medical issue, given the increasing number of patients receiving

immunosuppressants for organ transplantation or malignancy. Dissem-

inated or locally invasive infections can give rise to petechiae and hem-

Figure 122–13. Ecthyma gangrenosum. Associated with Gram-negative

sepsis, disseminated fungal infection, or other serious infectious dis- orrhagic necrosis. Common fungal pathogens in disseminated disease

eases, these hemorrhagic bullae evolve from erythematosus plaques, includes Candida (Fig. 122–16), Aspergillus (Fig. 122–17), Histoplasma,

103

both of which are shown here. and Fusarium. Disseminated candidiasis can manifest as ecthyma

Kaushansky_chapter 122_p2097-2112.indd 2104 9/18/15 10:30 AM