Page 597 - 9780077418427.pdf

P. 597

/Volume/201/MHDQ233/tat78194_disk1of1/0073378194/tat78194_pagefile

tiL12214_ch23_565-596.indd Page 574 9/23/10 11:07 AM user-f465

tiL12214_ch23_565-596.indd Page 574 9/23/10 11:07 AM user-f465 /Volume/201/MHDQ233/tat78194_disk1of1/0073378194/tat78194_pagefiles

frontal weather maker because it is not moving. Actually, a sta- center. After forming, the low-pressure cyclonic storm contin-

tionary front represents an unstable situation that can result in a ues moving, taking the associated stormy weather with it in a

major atmospheric storm. This type of storm is discussed in the generally easterly direction. Such cyclonic storms usually follow

section on waves and cyclones. principal tracks along a front (Figure 23.13). Since they are ob-

served generally to follow these same tracks, it is possible to pre-

dict where the storm might move next.

WAVES AND CYCLONES A cyclone is defined as a low-pressure center where the

A stationary front often develops a bulge, or wave, in the bound- winds move into the low-pressure center and are forced up-

ary between cool and warm air moving in opposite directions ward. As air moves in toward the center, the Coriolis effect (see

(Figure 23.12B). The wave grows as the moving air is deflected, chapter 16) and friction with the ground cause the moving air

forming a warm front moving northward on the right side and a to veer. In the Northern Hemisphere, this produces a counter-

cold front moving southward on the left side. Cold air is denser clockwise circulation pattern (Figure 23.14). The upward move-

than warm air, and the cold air moves faster than the slowly mov- ment associated with the low-pressure center of a cyclone cools

ing warm front. As the faster-moving cold air catches up with the the air, resulting in clouds, precipitation, and stormy conditions.

slower-moving warm air, the cold air underrides the warm air, Air is sinking in the center of a region of high pressure, pro-

lifting it upward. This lifting action produces a low-pressure area ducing winds that move outward. In the Northern Hemisphere,

at the point where the two fronts come together (Figure 23.12C). the Coriolis effect and frictional forces deflect this wind to the

The lifted air expands, cools by expansion, and reaches the dew right, producing a clockwise circulation (Figure 23.14). A high-

point. Clouds form and precipitation begins from the lifting and pressure center is called an anticyclone, or simply a high. Since

cooling action. Within days after the wave first appears, the cold air in a high-pressure zone sinks, it is warmed, and the relative

front completely overtakes the warm front, forming an occlu- humidity is lowered. Thus, clear, fair weather is usually associ-

sion (Figure 23.12D). An occluded front is one that has been ated with a high. By observing the barometric pressure, you can

lifted completely off the ground into the atmosphere. The distur- watch for decreasing pressure, which can mean the coming of a

bance is now a cyclonic storm with a fully developed low- pressure cyclone and its associated stormy weather. You can also watch

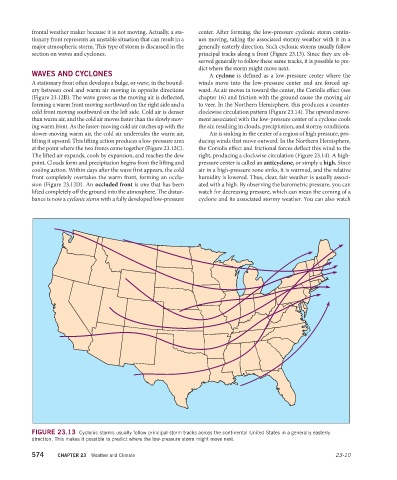

FIGURE 23.13 Cyclonic storms usually follow principal storm tracks across the continental United States in a generally easterly

direction. This makes it possible to predict where the low-pressure storm might move next.

574 CHAPTER 23 Weather and Climate 23-10